I found myself thinking about a girl from school, Meredtih Wittman who had lived on the same floor as me and Hannah and Angela, though the few times I said hi to her, she murmured something without looking at me or moving her mouth. A graduate of Andover, she carried her books in a Christian Dior bag and had once written a feature for the student newspaper's weekly magazine about Boston's salsa and merengue scene. I happened to know, because I had overheard her telling her friend Bridey, that Meredith Wittman was doing a summer internship at New York magazine, and for a moment now I reflected on the fact that, although Meredith Wittman and I both wanted to be writers, she was going about it by interning at a magazine, whereas I was sitting at this table in a Hungarian village trying to formulate the phrase "musically talented" in Russian, so I could say something encouraging by proxy to an off-putting child whose father had just punched him in the stomach. I couldn't help thinking that Meredith Wittman's approach seemed more direct.

I love this book so much. Much more than I expected to. Much more than I recall loving any other book in recent memory. I love it in a deeply personal way. It is urging me to closely consider how I judge books.

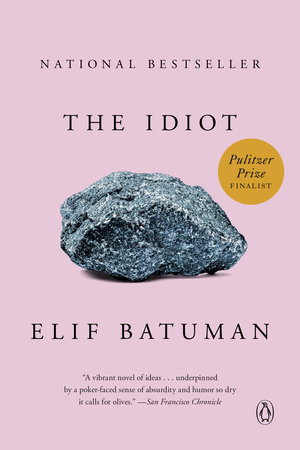

Not by the cover. It's pink, a horrific millennial shade of it. There's a picture of a rock. Too literal a representation of the title. The cover is so awful, I'm starting to like it. ("You can't just tell an ache: 'Go back into the rock.'"

Neruda's atom to return to blind stone.)

Not by the title. The title is not original. The author blatantly stole it from another book, a book with its own reputation that I've never read.

By the plot? Very little

happens. There is no situation requiring resolution. Except maybe the element that may be called a love story, but that element fades in and out — it's barely there.

Characters. Are not fully formed. Rather, they are fully formed representations of not yet fully formed people. People come and go. We only know them as much as the narrator gives them the time of day, considers how they impact her own life. She doesn't know how most of them fit into her own narrative yet.

So here I am thinking it can't be a very great book. It is not Dostoyevskian, I don't think. But how is it that I love it so? Why do I think of it as a guilty pleasure, that it is somehow not worthy of all my love. Is it not enough that this book brings me great joy? Why would I hesitate to give it 5 stars? Can the experience of reading the book be so much greater than the book itself? Does not the book itself earn the credit for giving me this experience?

The Idiot, by Elif Batuman, captures something delicate. I don't know if it is a universal experience, or a female experience, but it was

my experience.

It takes me back to my first year at university, and dorm living, and the cafeteria, and poring over the course catalogue, trying to figure out more that what I wanted to study: what kind of person I wanted to be. Did I want to be the kind of person who read about the history of magic and witchcraft, surveyed obscure fine arts movements, or enrolled in 19th-century literature?

What even is love, and do I want to be in it? How do people even talk to one another?

Selin's summer teaching English in Hungary is some ways also reflects a summer I spent in Poland — my roommate there was there teaching English (she didn't know any Polish, and she was ill-equipped to teach language; she was in an accounting program,

I was the linguistics major), phones were complicated, boys were complicated, communism hadn't entirely worn off yet. It was exciting, and sometimes very strange.

I've read a lot of negative comments about this book, about its pointlessness. People who dislike Selin, so self-absorbed, why doesn't she just say something?

When Vivie apologized for eating slowly, Béla said that eating slowly was good: "If you eat slowly, you can feel the food."

"You don't feel food," Owen said, "you taste it."

"Yes," Béla said. "But I also mean more than to taste it."

"You enjoy it," suggested Daniel. "If you eat slowly, you enjoy the food."

"You enjoy," repeated Béla.

"You relish it," said Owen. "You savor it."

"Savior?"

"Not savior — savor. It's like enjoying something, but more slowly."

"I don't know this word," Béla said, his eyes shining.

I realized that I would never have corrected somebody who said "you can feel the food." That was how Owen would end up with students who said "savor," while I wold end up with students who said "papel iss blonk."

I wouldn't correct it either. Of course you can feel the food, why would anyone correct that?

I can't help but feel that

The Idiot's naysayers are people who talk too much without saying anything substantial, who don't think before they speak; they either live in hypocrisy or their existence is charmed by self-assurance and obliviousness.

I've been thinking a lot about the kind of person I was when I was 18. I don't think I've changed much. Sure I've "evolved" — I know more stuff, I've had more experience. I form (and state) opinions more readily, because I have accumulated more arguments to back them up. I still obsess about language and figuring out what people are trying to say when they choose to say things (I do this professionally). The naysayers — I am certain I would not have liked their insufferable 18-year-old selves. I would not have liked Meredith Wittman.

The Guardian describes how

The Idiot is a historical novel, set at the advent of the internet but before smartphones, so this story could not have happened at any other time. At any other time, the plot would have to be different. But I think the story would be the same, youth is the same. (My university experience was pre-email. But it was the same.)

NPR:

Teenage pretention, unlike its later incarnations, has always seemed to me to be a kind of thrilling, experimental optimism: Is this who I could be? The Idiot is full of that wonderful, embarrassing kind of early pretention that consists of trying on roles like coats. (Selin buys a coat because it reminds her of Gogol).

[...]

The Idiot encapsulates those years of humiliating, but vibrant, confusion that come in your late teens, a confusion that's not even sexual, but existential and practical: Where do people get their opinions from? "How did you separate where someone was from, from who they were?" How do I "dispose of my body in space and time, every minute of every day, for the rest of my life?"

Big, beautiful messy life!

Interview with Elif Batuman at The Rumpus.