Over the last month, Poilly, Helena's lion puppet with the weird hair, has resumed a position of favour, attending daycare with her regularly and sharing her bed at night. Suddenly he is 3 years old. His mother is Kicia, a regular orange house cat (a toy) with a red bow; she is 5 years old now.

Whenever Helena picks up Poilly to take him anywhere — to daycare, shopping, for a walk — he cries for his mother, doesn't want to leave her, but Helena takes him anyway.

Over breakfast, Helena talks to me about Poilly. "Did you know his father's dead?" Umm, no, I didn't know.

Poilly's father went into the forest one day, and a witch lives there, with a pointy nose, and she took her broom and poked him with it, over and over, till he fell into the street and a car ran over him. And he died.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

Slapped cheeks

Sunday. I wake up and can't feel my fingers. This is unusual, I think. The house is cold, and I've always had poor circulation — I can't remember my hands and feet ever not being cold in winter — but this is extreme. I must have coffee, warm up. Nothing to do but start the day. I move to swing my legs over the side of the bed, but my knees are less than cooperative. This is strange, I think. Something's not right.

I have a hard time moving my fingers. I'm walking slow, cuz I hurt. There are things to do around the house, some groceries to pick up, the kid to hang out with. Finding a clinic open on Sunday is more trouble than grinning and bearing it and waiting till morning. I have a hot soak in the middle of the day. I know something's not right.

Monday. I wake up with swollen hands and stiff knees. And stiff elbows and swollen ankles. I get the family out the door and determine to arm myself with a little internet research before hying myself to a clinic.

"Research" (that is, googling symptom key words) doesn't get me beyond rheumatoid arthritis. I'm unable to determine whether one can succumb to the affliction overnight. I'm certain I'm going to die. I will gradually lose all mobility, and one morning later this week I'll wake up petrified, stone-still, dead.

Research into my death grinds to a halt when the phone rings. J-F is bringing Helena home. The daycare called him to pick her up. She's got a bit of a rash. They think it might be la cinquième maladie.

Never heard of it. It couldn't possibly go by that name in English, could it? I google in French and English. There it is. Fifth disease, erythema infectiosum, parvovirus B19, slapped-cheek disease.

A respiratory virus. I scan for symptoms. Low-grade fever, runny nose, fatigue; general flu-like symptoms. I suppose Helena may have it, or she may have a cold or flu. Cheeks that look like they've been slapped — Helena and I are generally red-cheeked all winter.

Then suddenly I see the damning evidence on all sides.

"Adults usually get a more severe case, with fever and painful joints." Adults can develop "joint pain or swelling... The joints most frequently affected are the hands, wrists, and knees." "Self-limited arthritis." "Acute polyarthropathy... usually involving finger joints."

Now I'm certain Helena has it, because I'm certain I have it too.

I call the pediatrician's office. Another doctor at the clinic has walk-in hours that afternoon. We arrive early so that we can wait 2 hours. I made the mistake of grabbing a sudoku book instead of my novel on the way out the house — it's damn near impossible for me to grip a pencil. But after 2 hours, Helena pretty much has the basic premise down and can write numbers in for me. She's bored and impatient, but remarkably sweet and good. She befriends a young toddler whom she helps to toddle.

The daycare will not allow Helena to return without a doctor's note. I'm miffed by the daycare's alarmist attitude, the implied judgement on my negligent mothering. But after 2 hours of sitting and overthinking, I realize they don't need a diagnosis, they just need a doctor's confirmation. They already know that the disease is self-limiting, and that Helena is well enough to participate in usual daycare activities. They already know that Helena's rash is a late stage of the disease, well past infectious. But they do need to advise employees and the parents of all attendees that there's been a confirmed case and that it poses a risk to pregnant women.

The doctor takes one look at Helena's forearms and confirms the diagnosis. While she obliges us with a note for daycare, I fish for information about my own condition, I say I think I have it too. She taps her own cheeks to indicate the bright red splotches across mine and nods slightly. She flexes her own hands, advising, in a word, "Tylenol." You don't need to see a doctor (unless you're pregnant); there's nothing a doctor can do.

I wake up today with the same hands that don't quite work and still-slow knees. This may go on all week, possibly for many weeks. "Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, joint pain worsens over the day, and no joint destruction occurs." Movement doesn't exactly get any easier throughout the day, but after a couple hours I get used to it.

Helena wants desperately to stay home today and I let her, though this is contrary to the advice for me to rest and restrict my activity. Everyday chores previously merely distasteful are now fully painful: unloading the dishwasher (without dropping anything); gripping the scoop to clean the cat litter; gripping heavy, wet laundry to whip it into the dryer; gripping a knife to chop vegetables. (Never mind uncorking a wine bottle.) For some things, I breathe deep and force it: doing up her buttons when she asks for help, cutting up her meat, colouring pictures with her.

I've never known anyone who's been struck by this kind of temporary, severe arthritis. I'm mystified that a virus and a body can come together to yield this kind of result. It's a strange thing, a unique experience I don't quite know what to make of yet. I have a window onto other people's pain-filled lives. It may be a glimpse of my own future, a decade or 2 or more from now.

I've been slapped hard.

I have a hard time moving my fingers. I'm walking slow, cuz I hurt. There are things to do around the house, some groceries to pick up, the kid to hang out with. Finding a clinic open on Sunday is more trouble than grinning and bearing it and waiting till morning. I have a hot soak in the middle of the day. I know something's not right.

Monday. I wake up with swollen hands and stiff knees. And stiff elbows and swollen ankles. I get the family out the door and determine to arm myself with a little internet research before hying myself to a clinic.

"Research" (that is, googling symptom key words) doesn't get me beyond rheumatoid arthritis. I'm unable to determine whether one can succumb to the affliction overnight. I'm certain I'm going to die. I will gradually lose all mobility, and one morning later this week I'll wake up petrified, stone-still, dead.

Research into my death grinds to a halt when the phone rings. J-F is bringing Helena home. The daycare called him to pick her up. She's got a bit of a rash. They think it might be la cinquième maladie.

Never heard of it. It couldn't possibly go by that name in English, could it? I google in French and English. There it is. Fifth disease, erythema infectiosum, parvovirus B19, slapped-cheek disease.

A respiratory virus. I scan for symptoms. Low-grade fever, runny nose, fatigue; general flu-like symptoms. I suppose Helena may have it, or she may have a cold or flu. Cheeks that look like they've been slapped — Helena and I are generally red-cheeked all winter.

Then suddenly I see the damning evidence on all sides.

"Adults usually get a more severe case, with fever and painful joints." Adults can develop "joint pain or swelling... The joints most frequently affected are the hands, wrists, and knees." "Self-limited arthritis." "Acute polyarthropathy... usually involving finger joints."

Now I'm certain Helena has it, because I'm certain I have it too.

I call the pediatrician's office. Another doctor at the clinic has walk-in hours that afternoon. We arrive early so that we can wait 2 hours. I made the mistake of grabbing a sudoku book instead of my novel on the way out the house — it's damn near impossible for me to grip a pencil. But after 2 hours, Helena pretty much has the basic premise down and can write numbers in for me. She's bored and impatient, but remarkably sweet and good. She befriends a young toddler whom she helps to toddle.

The daycare will not allow Helena to return without a doctor's note. I'm miffed by the daycare's alarmist attitude, the implied judgement on my negligent mothering. But after 2 hours of sitting and overthinking, I realize they don't need a diagnosis, they just need a doctor's confirmation. They already know that the disease is self-limiting, and that Helena is well enough to participate in usual daycare activities. They already know that Helena's rash is a late stage of the disease, well past infectious. But they do need to advise employees and the parents of all attendees that there's been a confirmed case and that it poses a risk to pregnant women.

The doctor takes one look at Helena's forearms and confirms the diagnosis. While she obliges us with a note for daycare, I fish for information about my own condition, I say I think I have it too. She taps her own cheeks to indicate the bright red splotches across mine and nods slightly. She flexes her own hands, advising, in a word, "Tylenol." You don't need to see a doctor (unless you're pregnant); there's nothing a doctor can do.

I wake up today with the same hands that don't quite work and still-slow knees. This may go on all week, possibly for many weeks. "Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, joint pain worsens over the day, and no joint destruction occurs." Movement doesn't exactly get any easier throughout the day, but after a couple hours I get used to it.

Helena wants desperately to stay home today and I let her, though this is contrary to the advice for me to rest and restrict my activity. Everyday chores previously merely distasteful are now fully painful: unloading the dishwasher (without dropping anything); gripping the scoop to clean the cat litter; gripping heavy, wet laundry to whip it into the dryer; gripping a knife to chop vegetables. (Never mind uncorking a wine bottle.) For some things, I breathe deep and force it: doing up her buttons when she asks for help, cutting up her meat, colouring pictures with her.

I've never known anyone who's been struck by this kind of temporary, severe arthritis. I'm mystified that a virus and a body can come together to yield this kind of result. It's a strange thing, a unique experience I don't quite know what to make of yet. I have a window onto other people's pain-filled lives. It may be a glimpse of my own future, a decade or 2 or more from now.

I've been slapped hard.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

Resonance

res·o·nance

n.

1. The quality or condition of being resonant: words that had resonance throughout his life.

2. Richness or significance, especially in evoking an association or strong emotion: "It is home and family that give resonance . . . to life" George Gilder. "Israel, gateway to Mecca, is of course a land of religious resonance and geopolitical significance" James Wolcott.

3. Physics The increase in amplitude of oscillation of an electric or mechanical system exposed to a periodic force whose frequency is equal or very close to the natural undamped frequency of the system.

4. Physics A subatomic particle lasting too short a time to be observed directly. The existence of such particles is usually inferred from a peak in the energy distribution of its decay products.

5. Acoustics Intensification and prolongation of sound, especially of a musical tone, produced by sympathetic vibration.

6. Linguistics Intensification of vocal tones during articulation, as by the air cavities of the mouth and nasal passages.

7. Medicine The sound produced by diagnostic percussion of the normal chest.

8. Chemistry The property of a compound having simultaneously the characteristics of two or more structural forms that differ only in the distribution of electrons. Such compounds are highly stable and cannot be properly represented by a single structural formula.

I'm reading something... important.

It happens occasionally that a book comes along. A book comes along at the right time in the right place. It seems to be happening more frequently these days. Maybe I'm reading better books. Maybe I've become a better reader. Maybe I'm simply paying better attention. Some books come with personal baggage before I ever open them, an overwhelming sense of having a specific import to me as an individual (Middlemarch); some books are a suitcase of global, historical significance, though the world may not know it yet and I can only guess (Snow).

I'm reading Richard Powers' The Gold Bug Variations and I am in love.

It feels important.

From the very first pages I knew I was reading something big. Every page resonates with me, on different levels, for sometimes trivial reasons, essential ones too. It's clear at this point (a couple hundred pages in) that it is important to me personally, but I sense that it's bigger than that.

"And I learn again, in my nerve endings, that information is never the same as knowledge."

"...when I still believed in the potential of democratically available facts..."

"Recognition, learning a thing by heart: life will be nothing after these go."

Even this insignificant scene:

It resonates, as I recall the very funniest Saturday Night Live bit, with Christopher Walken, that I've ever seen. (Why do I think it's so funny? It's hilarious, missing the point is.)

A coincidence: I turned on the radio last weekend and, for my benefit alone, there was Francis Collins, who headed the Human Genome Project, in interview.

There is a message in this book for me.

Then a reference to the Pythagoreans: "They say that things themselves are Numbers." I've always had a certain fondness for the Pythagoreans.

I feel my own knot tighten again.

I remember Mr Veenstra with the crazy accent, grade 9 science, who made you do push-ups if you broke the rules of the lab. He sent me to the principal's office when I refused my sentence, on principle, after I'd baited him, deliberately dawdling while leaving my safety goggles on my desk. I remember the frustration of skipping from chemistry to biology when I still felt gaps in my understanding, and I stayed after class to puzzle out the difference between molecules in animate and inanimate object. "That, Ms Kratynski," — his eyes were on fire, mine were all water — "is the $64,000 question."

On page 88 I find the joke I always used to make, that we need a map, ideally scaled 1:1, only to discover Lewis Carroll had cracked it before me.

Everything resonates.

There is awe on every page, reminding me of the awe I feel, on good days, in real life, regarding those two most awe-inspiring things: science and music. (There is love, too, but it a mechanism, not the message — the grammar through which all awe is known.) And when I close the book before closing my eyes at night, I am in awe of the pages I've just read.

I find my theory of everything in these pages: "Motion is not forward but concentric."

Ressler asks, "Can you look at a score and tell . . . simply by the pattern of notes, whether the composer has uncovered something correct?"

In the back of my mind hovers the question, is there a novel that is "something correct," mathematically necessary, or obvious.

Coincidentally I'd been listening to Glenn Gould's 1955 Goldberg Variations — the same recording referred to in the text. Maybe it was a subconscious preparation for immersion in this novel. I've been listening to it ever since. Nonstop for weeks now. It's breathtaking.

I need to know how it all ends.

n.

1. The quality or condition of being resonant: words that had resonance throughout his life.

2. Richness or significance, especially in evoking an association or strong emotion: "It is home and family that give resonance . . . to life" George Gilder. "Israel, gateway to Mecca, is of course a land of religious resonance and geopolitical significance" James Wolcott.

3. Physics The increase in amplitude of oscillation of an electric or mechanical system exposed to a periodic force whose frequency is equal or very close to the natural undamped frequency of the system.

4. Physics A subatomic particle lasting too short a time to be observed directly. The existence of such particles is usually inferred from a peak in the energy distribution of its decay products.

5. Acoustics Intensification and prolongation of sound, especially of a musical tone, produced by sympathetic vibration.

6. Linguistics Intensification of vocal tones during articulation, as by the air cavities of the mouth and nasal passages.

7. Medicine The sound produced by diagnostic percussion of the normal chest.

8. Chemistry The property of a compound having simultaneously the characteristics of two or more structural forms that differ only in the distribution of electrons. Such compounds are highly stable and cannot be properly represented by a single structural formula.

I'm reading something... important.

It happens occasionally that a book comes along. A book comes along at the right time in the right place. It seems to be happening more frequently these days. Maybe I'm reading better books. Maybe I've become a better reader. Maybe I'm simply paying better attention. Some books come with personal baggage before I ever open them, an overwhelming sense of having a specific import to me as an individual (Middlemarch); some books are a suitcase of global, historical significance, though the world may not know it yet and I can only guess (Snow).

I'm reading Richard Powers' The Gold Bug Variations and I am in love.

It feels important.

From the very first pages I knew I was reading something big. Every page resonates with me, on different levels, for sometimes trivial reasons, essential ones too. It's clear at this point (a couple hundred pages in) that it is important to me personally, but I sense that it's bigger than that.

"And I learn again, in my nerve endings, that information is never the same as knowledge."

"...when I still believed in the potential of democratically available facts..."

"Recognition, learning a thing by heart: life will be nothing after these go."

Even this insignificant scene:

Tooney Blake, dark, mid-height, a youthful forty, is at the piano doing a terrifyingly down-tempo version of "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off." Only he's missed the point of the song: "Potato, potato, tomato, tomato," all pronounced exactly the same.

It resonates, as I recall the very funniest Saturday Night Live bit, with Christopher Walken, that I've ever seen. (Why do I think it's so funny? It's hilarious, missing the point is.)

A coincidence: I turned on the radio last weekend and, for my benefit alone, there was Francis Collins, who headed the Human Genome Project, in interview.

There is a message in this book for me.

Half of what I made out about the twenty-five-year-old scientist was pure projection. I began to feel I had not lived up to my own intellect, that I'd been born too late, had taken a wrong turn, had lost my own chance to turn up the edge of the real, discover something, something hard. This child scientist, desperate with ability, somehow reduced to full-scale adult withdrawal, night shift labor, by something not explained in the literature: here was my own irreversible missed hour.

[...]

But something else motivates the euphoric articles, something more than self-aggrandizement, more than the desire to cap the ancient monument and book passage to Stockholm, that freezing, pristine Valhalla. The compulsion to find the pattern of living translation — the way a simple, self-duplicating string of four letters inscribes an entire living being — is built into every infant who has ever learned a word, put a phrase together, discovered that phonemes might speak.

As the journal evidence accumulated, it sucked me into the craze of crosswords, pull of punch lines, addiction to anagrams, nudge of numerology, suspense of magic squares. I felt the fresh PhD's suspicion that beneath the congenital complexity of human affairs runs a generating formula so simple and elegant that redemption depended on uncovering it. Once lifting the veil and glimpsing the underlying plan, Ressler would never again surrender its attempted recovery. The desire surpassed that for food, sex, even bedtime stories, worth pursuing with convert's zeal, with the singleness of a monastic, a lost substance abuser, a true habitué: the siege of concealed meaning.

Then a reference to the Pythagoreans: "They say that things themselves are Numbers." I've always had a certain fondness for the Pythagoreans.

The search for a starting point begins to resemble that painful process of elimination from freshman year, spent in the university clinic, a knot across my abdomen from having to choose which million disciplines I would exclude myself from forever.

I feel my own knot tighten again.

I remember Mr Veenstra with the crazy accent, grade 9 science, who made you do push-ups if you broke the rules of the lab. He sent me to the principal's office when I refused my sentence, on principle, after I'd baited him, deliberately dawdling while leaving my safety goggles on my desk. I remember the frustration of skipping from chemistry to biology when I still felt gaps in my understanding, and I stayed after class to puzzle out the difference between molecules in animate and inanimate object. "That, Ms Kratynski," — his eyes were on fire, mine were all water — "is the $64,000 question."

On page 88 I find the joke I always used to make, that we need a map, ideally scaled 1:1, only to discover Lewis Carroll had cracked it before me.

Everything resonates.

Science is not about control. That is technology, another urge altogether. The pursuit of living pattern that possessed Ressler has nothing to do with this year's apotheosis of bioengineering. He once remarked that mistaking science for technology deprived the nonscientist of one of the greatest sources of awe, replacing it with diet as filling as Tantalus's fruit. I had only to hear the man talk for fifteen minutes to realize that science had no purpose. The purpose of science, if one must, was the purpose of being alive: not efficiency or mastery, but the revival of appropriate surprise.

There is awe on every page, reminding me of the awe I feel, on good days, in real life, regarding those two most awe-inspiring things: science and music. (There is love, too, but it a mechanism, not the message — the grammar through which all awe is known.) And when I close the book before closing my eyes at night, I am in awe of the pages I've just read.

I find my theory of everything in these pages: "Motion is not forward but concentric."

Ressler asks, "Can you look at a score and tell . . . simply by the pattern of notes, whether the composer has uncovered something correct?"

In the back of my mind hovers the question, is there a novel that is "something correct," mathematically necessary, or obvious.

Coincidentally I'd been listening to Glenn Gould's 1955 Goldberg Variations — the same recording referred to in the text. Maybe it was a subconscious preparation for immersion in this novel. I've been listening to it ever since. Nonstop for weeks now. It's breathtaking.

There is nothing to do except release side one, track one. He touches the needle down on the Goldberg aria. The first sound of the octave, the simplicity of unfolding triad initiates a process that will mutate his insides for life. The transparent tones, surprising his mind in precisely the right state of confusion and readiness, suggest a concealed message of immense importance. But he comes no closer to naming the finger-scrape across the keys. The pleasure of harmony — subtle, statistical sequence of expectation and release — he can as yet only dimly feel. But the first measure announces a plan of heartbreaking proportions. What he fails to learn from these notes tonight will lodge in his lungs until they stop pumping.

I need to know how it all ends.

"You've worked in a lab, you've scribbled in enough notebooks to know better. I tell you, the world in not modulations and desire. It is stuff, pure and simple."

Thursday, February 22, 2007

Make 'em laugh

The grown-ups' birthdays in this household tend to go without much celebration in recent years — mine is the day after Helena's, J-F's just a few days before Christmas.

This year for J-F's birthday I bought a DVD. The movie as a whole was not intended as the gift; rather just one specific scene. Helena led him into the living room where a cappuccino and becandled day-old muffin were awaiting him. The movie already cued up, I pressed play, and we watched Donald O'Connor make 'em laugh, make us laugh.

I'd never seen Singin' in the Rain when I was growing up. My mother didn't care for Gene Kelly. If ever the movie was on TV during my childhood, it was passed over, for Bing Crosby or for the news. Of course, I knew the song — everyone knows that song. But it didn't mean anything to me.

It was a few years ago that we stumbled on some television program featuring classic movie moments or dance sequences or some such, and amid the hilarity, J-F made the bold pronouncement (shh, don't tell anyone) that Singin' in the Rain was one of the best movies, and O'Connors' Make 'Em Laugh one of the best scenes, ever. Now that I've seen it for myself, I agree. Even in my dourest moods, the finale of this number never fails to elicit deep and sincere spasms from my belly.

It seemed right this birthday to give the gift of laughter, start the new year on a laughing foot.

What I didn't foresee was the impact of this movie, this scene, on Helena.

From that first viewing on J-F's birthday morning Helena was fascinated. Interestingly, the title number resonates least of all (though it gives her some context, a cultural reference, for the Gene Kelly Muppet Show episode).

But when the mood here is musical she will take a jazz stance and proclaim "gotta dance!"

She sings Good Morning, loudly and clearly when we take the metro, putting smiles on other people's face. I cringe a little at the now less-than-innocent connotations, but I smile too, for reasons they cannot know, for the joy this film and this little girl bring to my household.

She exercises her booming low voice and squeaky high voice. "No, no, no," as she nods, and "yes, yes, yes," shaking her head emphatically. It's a bit she's found good for bringing levity to the yes/no questions I may ask her at trying times.

But it's Make 'Em Laugh that captivates her, that she requests repeatedly. She is perfecting her pinwheel, running circles round her shoulder on the floor. She is learning to rubberize her face. She is examining the possibility of running up the wall.

She's studying the humour, mining it for material.

Make 'em laugh, little girl.

(I started writing this post exactly 2 months ago today when I first noticed a little phenomenon that has since ballooned. I've been struggling all week with getting much of anything done, and for some reason this has been the biggest stumbling block of all. Though it's waited this long already, it's the thing I have to put to paper, to finish. It poses the problem of articulating very particular kinds of ineffable joy — that of one insignificant (in the grand scheme of things) movie scene, how it seems to punctuate the 3 lives intertwined in this household (and did so enthusiastically this last weekend), and that of the child, both in what she experiences and in what she brings to others. How does one write seriously about laughter without the writing itself being comedic, or slapstick? How do you capture laughter without being laughter? This is neither here nor there, really. Simply: I'm blocked. Writer's block, blogger's block. Fortunately, not laugher's block. I've never been one known to make 'em laugh, but beyond my expectations and contrary even to my own inclinations (and to any evidence in the tone you may hear here) this week I'm laughing with the best of 'em.)

This year for J-F's birthday I bought a DVD. The movie as a whole was not intended as the gift; rather just one specific scene. Helena led him into the living room where a cappuccino and becandled day-old muffin were awaiting him. The movie already cued up, I pressed play, and we watched Donald O'Connor make 'em laugh, make us laugh.

I'd never seen Singin' in the Rain when I was growing up. My mother didn't care for Gene Kelly. If ever the movie was on TV during my childhood, it was passed over, for Bing Crosby or for the news. Of course, I knew the song — everyone knows that song. But it didn't mean anything to me.

It was a few years ago that we stumbled on some television program featuring classic movie moments or dance sequences or some such, and amid the hilarity, J-F made the bold pronouncement (shh, don't tell anyone) that Singin' in the Rain was one of the best movies, and O'Connors' Make 'Em Laugh one of the best scenes, ever. Now that I've seen it for myself, I agree. Even in my dourest moods, the finale of this number never fails to elicit deep and sincere spasms from my belly.

It seemed right this birthday to give the gift of laughter, start the new year on a laughing foot.

What I didn't foresee was the impact of this movie, this scene, on Helena.

From that first viewing on J-F's birthday morning Helena was fascinated. Interestingly, the title number resonates least of all (though it gives her some context, a cultural reference, for the Gene Kelly Muppet Show episode).

But when the mood here is musical she will take a jazz stance and proclaim "gotta dance!"

She sings Good Morning, loudly and clearly when we take the metro, putting smiles on other people's face. I cringe a little at the now less-than-innocent connotations, but I smile too, for reasons they cannot know, for the joy this film and this little girl bring to my household.

She exercises her booming low voice and squeaky high voice. "No, no, no," as she nods, and "yes, yes, yes," shaking her head emphatically. It's a bit she's found good for bringing levity to the yes/no questions I may ask her at trying times.

But it's Make 'Em Laugh that captivates her, that she requests repeatedly. She is perfecting her pinwheel, running circles round her shoulder on the floor. She is learning to rubberize her face. She is examining the possibility of running up the wall.

She's studying the humour, mining it for material.

Make 'em laugh, little girl.

(I started writing this post exactly 2 months ago today when I first noticed a little phenomenon that has since ballooned. I've been struggling all week with getting much of anything done, and for some reason this has been the biggest stumbling block of all. Though it's waited this long already, it's the thing I have to put to paper, to finish. It poses the problem of articulating very particular kinds of ineffable joy — that of one insignificant (in the grand scheme of things) movie scene, how it seems to punctuate the 3 lives intertwined in this household (and did so enthusiastically this last weekend), and that of the child, both in what she experiences and in what she brings to others. How does one write seriously about laughter without the writing itself being comedic, or slapstick? How do you capture laughter without being laughter? This is neither here nor there, really. Simply: I'm blocked. Writer's block, blogger's block. Fortunately, not laugher's block. I've never been one known to make 'em laugh, but beyond my expectations and contrary even to my own inclinations (and to any evidence in the tone you may hear here) this week I'm laughing with the best of 'em.)

The slaves of Patrick Hamilton

David Lodge sings the praises of The Slaves of Solitude, by Patrick Hamilton, calling it one of the very best English novels written about the second world war. (Link via Tom Roper). It's a great introduction to a book I now pronounce (I'm a little slow to commit to such bold statements) as one of my all-time greatest reads.

The book has just been reissued by NYRB Classics. I don't have a copy yet, but Susan does (maybe she can tell us whether this article and Lodge's print introduction to the reissue are one and the same).

The Slaves of Solitude was the first Patrick Hamilton book I read — a serendipitous library find — and it hooked me. You'll be hearing even more about him from me as I work through his two big ones over the next couple months. I intend to read everything of his I can get my hands on.

I'm pleased to learn also that The Gorse Trilogy is set to be reissued in June 2007 (Black Spring Press). Having read the first two parts and being unable to find the third, I'm, well, really excited! I can't wait!

The book has just been reissued by NYRB Classics. I don't have a copy yet, but Susan does (maybe she can tell us whether this article and Lodge's print introduction to the reissue are one and the same).

The Slaves of Solitude was the first Patrick Hamilton book I read — a serendipitous library find — and it hooked me. You'll be hearing even more about him from me as I work through his two big ones over the next couple months. I intend to read everything of his I can get my hands on.

I'm pleased to learn also that The Gorse Trilogy is set to be reissued in June 2007 (Black Spring Press). Having read the first two parts and being unable to find the third, I'm, well, really excited! I can't wait!

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

In which my sister attends a reading at my insistence and then tells me about it

That is: author appearance, a report by proxy.

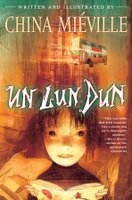

China Miéville wasn't appearing at a bookstore near me, but he was appearing at one (very many miles away from where I live) that my sister frequents (well, has been to), so I told her to go, and for some inexplicable reason she listened to me (she hasn't read any Miéville) and even braved pouring rain to go hear him read from Un Lun Dun and ask on my behalf my now trademark question (although I'm sure nobody but me knows it, about it being my trademark I mean), "So, whatcha readin'?" (although I'm fairly certain my sister ad libbed it), it being at once casual, unpretentious, and sincere and having the potential for if not great insight then at least some pleasant alternatively warm-up or wind-down discussion.

He read chapter 5, and his reading was strong, sensible, and entertaining enough that 1) my sister was actually sucked into buying a copy of the book, even after I'd told her she shouldn't bother cuz it's not very good — (I don't really mean that, China. It's good, I liked it; I just didn't love it, it's like you were holding back, it could've been so much better. Be political! Be scary! The kids can take it!) — which has now been personally inscribed to my daughter, "for when she's ready to turn the iron wheel," and 2) she (my sister) is inspired to finally get 'round to reading something he's written, Perdido Street Station having sat unread on her shelf for a few years already.

He fielded questions for about an hour from a fairly geeky-looking (so says my sister) audience, a lesser turnout than for other DC-area readings my sister has attended, and would not be goaded into trashing either Tolkien (his views are on the record) or Star Trek. While he mocked the accuracy of Amazon and Wikipedia regarding future publications and speculated on the life cycle of rumour, he did not unequivocally deny that he was at work on a novel called Kraken.

Also, apparently Miéville has a sexy laugh.

What China Miéville is currently reading:

The Ideology of the Aesthetic, by Terry Eagleton

Suttree, by Cormac McCarthy

Fire Sale, by Sara Paretsky

Any errors regarding what transpired at China Miéville's reading yesterday evening are likely my own, as my multitasking has on occasion proven to be deficient (and I was trying to load the dishwasher while listening on the phone) and sometimes I infer and extrapolate in accordance with my own subconscious desires and assumptions and am later unable to distinguish this from actual fact; or quite possibly my sister's, in either sloppy note-taking or her inability to read her own writing; or China Miéville's deliberate misinformation.

China Miéville wasn't appearing at a bookstore near me, but he was appearing at one (very many miles away from where I live) that my sister frequents (well, has been to), so I told her to go, and for some inexplicable reason she listened to me (she hasn't read any Miéville) and even braved pouring rain to go hear him read from Un Lun Dun and ask on my behalf my now trademark question (although I'm sure nobody but me knows it, about it being my trademark I mean), "So, whatcha readin'?" (although I'm fairly certain my sister ad libbed it), it being at once casual, unpretentious, and sincere and having the potential for if not great insight then at least some pleasant alternatively warm-up or wind-down discussion.

He read chapter 5, and his reading was strong, sensible, and entertaining enough that 1) my sister was actually sucked into buying a copy of the book, even after I'd told her she shouldn't bother cuz it's not very good — (I don't really mean that, China. It's good, I liked it; I just didn't love it, it's like you were holding back, it could've been so much better. Be political! Be scary! The kids can take it!) — which has now been personally inscribed to my daughter, "for when she's ready to turn the iron wheel," and 2) she (my sister) is inspired to finally get 'round to reading something he's written, Perdido Street Station having sat unread on her shelf for a few years already.

He fielded questions for about an hour from a fairly geeky-looking (so says my sister) audience, a lesser turnout than for other DC-area readings my sister has attended, and would not be goaded into trashing either Tolkien (his views are on the record) or Star Trek. While he mocked the accuracy of Amazon and Wikipedia regarding future publications and speculated on the life cycle of rumour, he did not unequivocally deny that he was at work on a novel called Kraken.

Also, apparently Miéville has a sexy laugh.

What China Miéville is currently reading:

The Ideology of the Aesthetic, by Terry Eagleton

Suttree, by Cormac McCarthy

Fire Sale, by Sara Paretsky

Any errors regarding what transpired at China Miéville's reading yesterday evening are likely my own, as my multitasking has on occasion proven to be deficient (and I was trying to load the dishwasher while listening on the phone) and sometimes I infer and extrapolate in accordance with my own subconscious desires and assumptions and am later unable to distinguish this from actual fact; or quite possibly my sister's, in either sloppy note-taking or her inability to read her own writing; or China Miéville's deliberate misinformation.

Friday, February 16, 2007

Un-China

I so wanted to love this book. And I so wish I were 12 — maybe then it'd be a little easier. As it is, I found it very easy to walk away from this book for hours, even days, at a time.

I so wanted to love this book. And I so wish I were 12 — maybe then it'd be a little easier. As it is, I found it very easy to walk away from this book for hours, even days, at a time.China Miéville wrote Un Lun Dun for young adults. The title comes from the name of a city in an alternate reality, which a couple kids slip into. Un Lun Dun. Un-London.

Miéville in a recent interview describes the book thusly:

It's a classic story of children from our world who find their way into another, odder place. The place is sort of a twisted city. It's a homage to that tradition of books like the Alice books, the Narnia books — cross-fertilised with the urban tradition of books like Michael de Larrabeiti's Borribles.

Un Lun Dun has a decidedly urban feel. The dialogue is modern and slangy (there's a glossary for the benefit of American readers); as an adult reader I find this off-putting — the story loses the sense of fabular timelessness I associate with YA lit — but the tone at least is even and consistent throughout the whole of the novel. The world is littered with clever ideas of characters, but none are fleshed out. The plot is nothing new: youngster trapped in another world in accordance with prophecy must battle a villain before finding her way home.

Miéville talks a lot about breaking the conventions of the fantasy genre, but for some reason didn't see fit to do it here. It is a classic story. The prophecies are flawed, but this is a mere joke, not an overturning of the narrative formula.

(One character spouts out Humpty Dumpty's old line, that words mean whatever he wants them to mean. I love that Deeba argues back.)

The villain is a sentient gaseous cloud: Smog. Smog was apparently previously battled and beaten in London by the Klinneract. Deeba does some research and digs up the Clean Air Act. I half hoped, half dreaded that Miéville might get political, impart on young readers some lesson regarding the environment. But no, just a little joke.

Everything about this book feels like a missed opportunity, a thin sketch. I'm not well versed in young adult literature, so I can't fairly gauge how it measures up against what the kids are reading these days (although I can with certainty say this no Narnia or Hogwarts). I'd been hoping for a scaled-down version of Bas-Lag (I really wouldn't want to take a child there, even if I do let my 4-year-old watch Doctor Who with me), something less monstrous but as richly peopled. This isn't it.

There are moments when the darker, more adult Miéville shines through, with evidence of things for which I love the Bas-Lag books, when describing, for example, architecture:

They were swaying before a huge building. It was like nothing she had ever seen.

It had no straight edges, was all long curving planes stretched like cloth or rubber. In several places it poked into steep cones, and pillars and jags like tree branches jutted from beneath its shimmering, moving surface. It looked like a load of giant tents, all stitched together at crazy random, as big as a stadium. Its entire surface was white, or gray-white, or yellow-white, and it rippled.

"Oh my gosh," whispered Deeba again. "It's a cobweb."

Tons of spider silk had been draped over an enormous irregular framework. It coated it completely, in layers, totally opaque. At its edges, strands of webbing jutted out at angles and anchored to the pavement and surrounding buildings like guyropes.

In one or two places, Deeba could see dark, immobile things smothered in the silk. It was wound around them in shrouds, suspending them in the building's substance.

"That'll be Webminster Abbey, then," said Hemi.

or monsters:

Through the Diss & Rosa's windshield, Deeba saw fingers of weed rise from the murk and stroke the underside of the metal. Deeba put her face close to the glass to watch them, then sat hurriedly back.

"It moved," she said.

The stuff floated around them. If drifted by in little islands. As Deeba watched it, one quivered, and reached out a tendril to grab a passing piece of rubbish. It hauled it in — it was a mouldy fish carcass — and the slimy clot of weed quivered more.

"That's shudderwrack," said Lectern. "Keep you hands out of the water."

But these atmospheric gems are few and far between.

Interestingly, of all the books I've handled recently, Helena is particularly attracted to this one. She loves the jacket design. She found the illustrations within, Miéville's own, to be very funny. So there's something to it, the book having an appeal to a younger crowd. (Helena insisted I start at the beginning with her, not to read, but to count the chapters.)

See Edward Champion's review.

Excerpt.

Tuesday, February 13, 2007

The rat

I love this book — Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, by Sam Savage, from Coffee House Press.

I love this book — Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, by Sam Savage, from Coffee House Press.It's charming. A rat who reads and eats books. Love and reverence for books. The comfort books provide both body and mind. While I'm drawn to books about books, booklovers' books, they often disappoint me — too much sentiment or too much sermon, often just meaningless name-dropping. In Firmin, the book-love is just enough in evidence without ever feeling like a cheap trick. Firmin the rat is hopelessly romantic; Firmin the novel is not.

From a very simple premise, we have a window onto humanity and despair through the cracks in the margins of existence. It's seedy, and brimming with life. And surprisingly gentle.

Firmin begins his life in a used books store; he is far too busy absorbing and being absorbed by books to know a real rat's life. It's a while before Firmin is able to distinguish fiction from nonfiction, and though he consumes plenty of it, it's questionable whether he ever fully digests it. Apart from books, Firmin's pleasure is to scurry out among the lowlifes to take in late-night pornographic movies at the local theatre, which carries a different kind of romance altogether. His world is turned upside down when he discovers all is not as he imagines it to be, people are not what they seem — the proprietor tries to kill him. Firmin sets out to make contact with humans; his effort is disastrous, but it brings him into a relationship, complicated and beautiful in its way, with the science fiction writer who lives upstairs from the shop. This time, Firmin has a greater understanding of the dynamic he has entered into:

Jerry talked and I listened. Gradually I learned more and more about his life, while he, one can safely say, learned less and less about mine. Due to my natural reticence, he had a free hand with my personality. He could pretty much make me into whomever he wanted, and it was soon painfully clear that when he looked at me what he mainly saw was a cute animal, clownish and a little stupid, something like a very small dog with buckteeth. He had no inkling of my true character, that I was in fact grossly cynical, moderately vicious, and a melancholy genius, or that I had read more books than he had. I love Jerry, but I feared that what he loved in return was not me but a figment of his imagination. I knew all about being in love with figments. And in my heart I always knew, although I liked to pretend otherwise, that during our evening together, when he would drink and talk, he was really just talking to himself.

The thing. Two things.

One: The novel opens with a couple epigrams, one being that old teaching "...he did not know whether he was a man dreaming that he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming that he was a man." In Firmin, there's a kind of metamorphosis, from rat to human, from fiction to life, and both back again.

Two: Jerry's novel is about an alien race that mistakes rats as the dominant species of Earth. (Which is maybe why Firmin likes Jerry.) It merits a little consideration, that there is something — no, not dominant, but — meaningful in the human rats, the marginalized, the forgotten, the drunks and the whores. What it is to be human. To be the protagonist of one's own narrative.

I began to spend most of every day on my back, all four feet in the air, dreaming and remembering, or else playing the piano, remembering and dreaming. I could see that my dreams were changing. They were getting soft and nostalgic, with a kind of crepuscular flare around the edges, and I didn't have many exciting adventures anymore. I missed the past terribly, even the awful parts. I never forget anything that has happened to me and scarcely anything that I have read, so by that time I had stored up an awful lot of memories. My brain was like a gigantic warehouse — you could get lost in it, lose track of time, peeking into boxes and cases, wandering knee-deep in dust, and not find your way our for days. Sometime shortly after I moved in with Jerry I had begun to play with the past, tweaking it this way and that to make it more like a real story, and I had begun mixing my memories with my dreams. This was probably a mistake, since the more I played with them the more they came to resemble each other, and it was harder and harder for me to tell the things I remembered from the things I invented. I was now, for example, unsure which of the figures was really Mama, the fat greedy one or the thin, worn sweet one, and whether her name was Flo of Deedee of Gwendolyn. All the archives existed only in my mind. I had no external check, no diary, no old family friend. How could I verify? All I could do was compare one mental image with another image, equally suspect, and in the end they all got tangled together. My mind was a labyrinth, enticing or terrifying according to my mood. I was losing my footing, and the odd thing was that I didn't care.

See the discussion at the LitBlog Co-op (a couple posts aren't properly tagged, including the comments by Sam Savage himself, so check the November archives to get all the good bits).

Really, an excellent read.

Monday, February 12, 2007

Counting the days

Helena was flipping through the pages of her calendar, and before I could think up an excuse to be elsewhere, she had me listening (feigned attentively) to her count every single effing day of every single effing month of the whole effing year. She knows how many days till her uncle's birthday (a handful), and how many to her own (very many). (My brain had glazed over and I'm unable to recall the exact numbers.)

Yesterday we played in the snow. Here Helena ceremoniously presents an emissary with a symbolic chunk of snow to appease the gods of winter, that the winds will not make ice statues of us, that the polar bears will not take us for popsicles.

Yesterday we played in the snow. Here Helena ceremoniously presents an emissary with a symbolic chunk of snow to appease the gods of winter, that the winds will not make ice statues of us, that the polar bears will not take us for popsicles.

Yesterday we played in the snow. Here Helena ceremoniously presents an emissary with a symbolic chunk of snow to appease the gods of winter, that the winds will not make ice statues of us, that the polar bears will not take us for popsicles.

Yesterday we played in the snow. Here Helena ceremoniously presents an emissary with a symbolic chunk of snow to appease the gods of winter, that the winds will not make ice statues of us, that the polar bears will not take us for popsicles.

Friday, February 09, 2007

Bits

What I'm thinking about:

Margaret Atwood's take on arts funding. If you haven't read it already, do. And check out the dirty little debate over it at Bookninja, where, if one must take sides, I'd be trumpeting merit over financial need. Not that any of this affects me personally, apart from my being a citizen-consumer of "art."

Atwood starts her piece hinting at a kind of art-brain-drain, a problem that might indeed be helped by having money thrown at it. But she doesn't go anywhere with that grain for an argument, and no one else is pecking at it, which has me thinking, more than anything, that my comprehension skills are defective and deficient.

What I'm puzzling over:

How to translate "twunt."

What I'm dreaming about:

Sex in space.

What made me sad:

Solveig Dommartin died.

What I'm reading:

I'm in the final stretch of China Miéville's Un Lun Dun. At some point this evening I'll retrieve from my go-everywhere bag Firmin, by Sam Savage, the opening pages of which had me laughing out loud on the metro earlier this week.

A week into February and I haven't cracked a chunkster — I'm leaning toward Powers' Goldbug Variations, it being the shortest of my options and thus seemingly perfectly suited to this shortest of months for my one-a-month plan. But I just don't know yet.

I never figured I was susceptible to the February blahs, but the last few years would give evidence to the contrary. This year, so far, so blah. Reading, blah. Blogging, blah. Cat puking all over my bed, blah. Helena home sick, blah.

What I'm listening to:

Thelonious Monk.

What I'm going to do next:

Nap. Me and Monk and Miéville, with the kid and the cat.

Margaret Atwood's take on arts funding. If you haven't read it already, do. And check out the dirty little debate over it at Bookninja, where, if one must take sides, I'd be trumpeting merit over financial need. Not that any of this affects me personally, apart from my being a citizen-consumer of "art."

Atwood starts her piece hinting at a kind of art-brain-drain, a problem that might indeed be helped by having money thrown at it. But she doesn't go anywhere with that grain for an argument, and no one else is pecking at it, which has me thinking, more than anything, that my comprehension skills are defective and deficient.

What I'm puzzling over:

How to translate "twunt."

What I'm dreaming about:

Sex in space.

What made me sad:

Solveig Dommartin died.

What I'm reading:

I'm in the final stretch of China Miéville's Un Lun Dun. At some point this evening I'll retrieve from my go-everywhere bag Firmin, by Sam Savage, the opening pages of which had me laughing out loud on the metro earlier this week.

A week into February and I haven't cracked a chunkster — I'm leaning toward Powers' Goldbug Variations, it being the shortest of my options and thus seemingly perfectly suited to this shortest of months for my one-a-month plan. But I just don't know yet.

I never figured I was susceptible to the February blahs, but the last few years would give evidence to the contrary. This year, so far, so blah. Reading, blah. Blogging, blah. Cat puking all over my bed, blah. Helena home sick, blah.

What I'm listening to:

Thelonious Monk.

What I'm going to do next:

Nap. Me and Monk and Miéville, with the kid and the cat.

Thursday, February 08, 2007

The Doctor and us

One of the things, of very many, that makes me a bad mommy (or, arguably, just feel like one) is that I watch Doctor Who with my 4-year-old daughter. (Is that hipster parenting, or what?)

Whether or not it's too narratively sophisticated for the 4-year-old mind, many parents would find it objectionable for its scary monsters, frightening situations, and violence.

(Helena's educateur had overheard her reminding her father that she'd be watching Doctor Who that evening, so he made a point of catching an episode himself. His only comment afterward to J-F: "weird." That sounds judgmental to me.)

None of these concerns outweighs my deep-seated need for a peaceful Monday evening watching my television program of choice. (Sure, I watch other programs, but none regularly.) We tried to get her to bed swiftly so that I'd be sitting comfortably and undisturbed by 8 o'clock, but she knew something was up — she dawdled, she resisted. And I was not willing to sacrifice this selfish pleasure for the sake of my daughter's well-being. So I walked away, and she followed me, and a monster of a habit was born.

I rationalize it. It's bonding time. It's not breastfeeding, or storytime, or a bath. It's something so completely outside ourselves, beyond the bonds dictated by family. It's a shared pop cultural experience.

I like that we've planted a seed of open-mindedness in her. A respect for science fiction. For space exploration. I like that she's introduced to idea of alien life and time travel, regardless of whether they're a real possibility, for the philosophical implications that must then be considered.

Helena loves monsters. And robots. Sometimes they scare her, but mostly they thrill her. Occasionally she whimpers a quiet "I'm scared" and burrows her face into my arm.

I'm not too worried about the "monsters," particularly when many of them are not essentially malevolent — they're just misunderstood, trying to survive.

The best part is, Helena asks questions.

(Possible spoilers ahead.)

This week's episode I was wary of. Children were disappearing off the streets. Creepy kids' drawings were coming to life, or trapping life. I feared Helena might take it a little more personally, relate it more directly her experience of life. But it was not so alarming as previews had suggested (episode guide).

An alien life form had essentially possessed the body of child. Its spaceship was broken. It was lost and lonely for its brothers and sisters. So it literally drew the London children into its energy field. But it wasn't a mean creature; itself it was a child, and doing what it could to survive, if a little selfishly and at the expense of others. The Doctor helped it go home.

We talked. Just because you're sad or lonely doesn't give you the right to do whatever you want. Just because you're young doesn't mean you can't be helped to understand and to do right.

We talked about drawing. How drawing can help you express your feelings. How it can make you feel better if you're sad or lonely. The difference between a drawing and reality. (One drawing depicted the girl's father as he appears in her nightmares, an emotionally twisted, dream version of reality.)

There are issues. Moral dilemmas. Logistical problems. Ongoing narrative developments. Things that are more sophisticated than contained in a half-hour Dora episode or a Kevin Henkes book. Things Helena's mind has the potential to grapple with, and some of that capacity is already afire.

The thing is, Helena likes Rose. (Not Barbie! Rose!) She asks where the Doctor is and cheers when he comes on screen, but she worries about Rose. And the thing about her liking Rose is, well, Rose is going to die.

Scenes from next week's episode reference a previous story in which the Beast said Rose would die in battle.

It's inevitable now. I know it's coming, if not next week, then soon. But I don't know how to brace Helena for it.

Whether or not it's too narratively sophisticated for the 4-year-old mind, many parents would find it objectionable for its scary monsters, frightening situations, and violence.

(Helena's educateur had overheard her reminding her father that she'd be watching Doctor Who that evening, so he made a point of catching an episode himself. His only comment afterward to J-F: "weird." That sounds judgmental to me.)

None of these concerns outweighs my deep-seated need for a peaceful Monday evening watching my television program of choice. (Sure, I watch other programs, but none regularly.) We tried to get her to bed swiftly so that I'd be sitting comfortably and undisturbed by 8 o'clock, but she knew something was up — she dawdled, she resisted. And I was not willing to sacrifice this selfish pleasure for the sake of my daughter's well-being. So I walked away, and she followed me, and a monster of a habit was born.

I rationalize it. It's bonding time. It's not breastfeeding, or storytime, or a bath. It's something so completely outside ourselves, beyond the bonds dictated by family. It's a shared pop cultural experience.

I like that we've planted a seed of open-mindedness in her. A respect for science fiction. For space exploration. I like that she's introduced to idea of alien life and time travel, regardless of whether they're a real possibility, for the philosophical implications that must then be considered.

Helena loves monsters. And robots. Sometimes they scare her, but mostly they thrill her. Occasionally she whimpers a quiet "I'm scared" and burrows her face into my arm.

I'm not too worried about the "monsters," particularly when many of them are not essentially malevolent — they're just misunderstood, trying to survive.

The best part is, Helena asks questions.

(Possible spoilers ahead.)

This week's episode I was wary of. Children were disappearing off the streets. Creepy kids' drawings were coming to life, or trapping life. I feared Helena might take it a little more personally, relate it more directly her experience of life. But it was not so alarming as previews had suggested (episode guide).

An alien life form had essentially possessed the body of child. Its spaceship was broken. It was lost and lonely for its brothers and sisters. So it literally drew the London children into its energy field. But it wasn't a mean creature; itself it was a child, and doing what it could to survive, if a little selfishly and at the expense of others. The Doctor helped it go home.

We talked. Just because you're sad or lonely doesn't give you the right to do whatever you want. Just because you're young doesn't mean you can't be helped to understand and to do right.

We talked about drawing. How drawing can help you express your feelings. How it can make you feel better if you're sad or lonely. The difference between a drawing and reality. (One drawing depicted the girl's father as he appears in her nightmares, an emotionally twisted, dream version of reality.)

There are issues. Moral dilemmas. Logistical problems. Ongoing narrative developments. Things that are more sophisticated than contained in a half-hour Dora episode or a Kevin Henkes book. Things Helena's mind has the potential to grapple with, and some of that capacity is already afire.

The thing is, Helena likes Rose. (Not Barbie! Rose!) She asks where the Doctor is and cheers when he comes on screen, but she worries about Rose. And the thing about her liking Rose is, well, Rose is going to die.

Scenes from next week's episode reference a previous story in which the Beast said Rose would die in battle.

It's inevitable now. I know it's coming, if not next week, then soon. But I don't know how to brace Helena for it.

Tuesday, February 06, 2007

Magic

Helena closes her eyes, tight, tight, tight, stretches out her arms, and wiggles her fingers. (Sometimes she uses a magic wand, but one isn't always on hand when you need it.) Slowly, loudly, she intones:

"Par la magie de mes doigts, [chose x] disparru!"

(Actually, "disparrait," would be the grammatically correct way about it, but she says what she says.)

The chant was inspired by her theatre class — they would bring the teacher's puppet to life, later returning it to its enchanted sleep.

Helena knows the power of magic.

The first thing she wanted to disappear was a tea towel. She was "helping" me fold laundry. Quick thinker that I am, with her eyes closed so tight, I swiped it away from in front of her and tucked it under the bed.

A glint in her eye, a gasp, and a smile. She proceeded to disappear the rest of the towels.

It's when she tried to use her skills in the bath — I was precariously perched, the props she chose were fragile or unwieldy, and hiding places were awkward — that it occurred to me I may have unwittingly enabled her to believe that she really had magical powers. Or perhaps it was just a test of my complicity.

She makes me disappear. And Papa. She magics us back into existence in odd places. For some reason, the magic doesn't work very well on the cat.

She asks us to make her disappear. She reminds us we have to close our eyes tight for the magic to work. We here her pitter-patter down the hall. We trace her by her giggles. Her act is complete with "where am I?" and "how did I get here?"

Sometimes she casts a spell with no warning and the magic doesn't take. I suggest she didn't have the right stance or a magical enough tone. Slower and louder gives me more time to work my magic.

Still, there are times I'm caught off guard, not fast enough, and she catches me in the act. I catch a quick scolding (no, mama, let the magic do it) and the glint in her eye: there are things of which we must not speak.

"Par la magie de mes doigts, [chose x] disparru!"

(Actually, "disparrait," would be the grammatically correct way about it, but she says what she says.)

The chant was inspired by her theatre class — they would bring the teacher's puppet to life, later returning it to its enchanted sleep.

Helena knows the power of magic.

The first thing she wanted to disappear was a tea towel. She was "helping" me fold laundry. Quick thinker that I am, with her eyes closed so tight, I swiped it away from in front of her and tucked it under the bed.

A glint in her eye, a gasp, and a smile. She proceeded to disappear the rest of the towels.

It's when she tried to use her skills in the bath — I was precariously perched, the props she chose were fragile or unwieldy, and hiding places were awkward — that it occurred to me I may have unwittingly enabled her to believe that she really had magical powers. Or perhaps it was just a test of my complicity.

She makes me disappear. And Papa. She magics us back into existence in odd places. For some reason, the magic doesn't work very well on the cat.

She asks us to make her disappear. She reminds us we have to close our eyes tight for the magic to work. We here her pitter-patter down the hall. We trace her by her giggles. Her act is complete with "where am I?" and "how did I get here?"

Sometimes she casts a spell with no warning and the magic doesn't take. I suggest she didn't have the right stance or a magical enough tone. Slower and louder gives me more time to work my magic.

Still, there are times I'm caught off guard, not fast enough, and she catches me in the act. I catch a quick scolding (no, mama, let the magic do it) and the glint in her eye: there are things of which we must not speak.

Monday, February 05, 2007

Listen to the radio

I've by chance tuned in to Wire Tap a few times, and after stumbling into it again yesterday, I'm convinced that it's the funniest, most wonderfully scripted and performed entertainment out there.

Show highlights are online.

In particular: Howard enlists Goldstein's help, Cyrano de Bergerac style, to pitch some poetry to the editor of the Regina Quarterly — "45 seconds, a very valuable commodity in the poetry world."

"The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation is not a metaphor; it's a broadcasting corporation."

Show highlights are online.

In particular: Howard enlists Goldstein's help, Cyrano de Bergerac style, to pitch some poetry to the editor of the Regina Quarterly — "45 seconds, a very valuable commodity in the poetry world."

"The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation is not a metaphor; it's a broadcasting corporation."

Drunroll, please...

Contest: Un Lun Dun-inspired place names.

Prize: Bang Crunch, by Neil Smith, signed by the author.

Winner: Danielle, of A Work in Progress, for Nomaha, which is beautiful in its simplicity. (Please email me, Danielle, with your postal address.)

Thanks, everyone, for playing. (I may have to do this again — it's an entertaining way to get rid of some of the excess books stacking up around here, as well as to discover some otherwise silent readers and their blogs.)

(I grew up in Sans Catharines (near Niagara Fell, or, in the opposite direction, Shamilton), Untario. I lived for many years in Nottawa. Oh, I could do this all day. I have been doing this, for far too many days, with random place names around the globe. Please get me outside of my own head.)

Prize: Bang Crunch, by Neil Smith, signed by the author.

Winner: Danielle, of A Work in Progress, for Nomaha, which is beautiful in its simplicity. (Please email me, Danielle, with your postal address.)

Thanks, everyone, for playing. (I may have to do this again — it's an entertaining way to get rid of some of the excess books stacking up around here, as well as to discover some otherwise silent readers and their blogs.)

(I grew up in Sans Catharines (near Niagara Fell, or, in the opposite direction, Shamilton), Untario. I lived for many years in Nottawa. Oh, I could do this all day. I have been doing this, for far too many days, with random place names around the globe. Please get me outside of my own head.)

Thursday, February 01, 2007

Un-place: contest! with prize!

(Originally posted January 30, 8:07 pm. I'll be keeping this post up top for a bit, cuz it's fun! you should play! even if you don't want the prize.)

One of the books I've been most looking forward to this winter is the new novel by China Miéville, this time writing for young adults. Un Lun Dun is set to hit store shelves February 13, but I'll be tucking into my review copy tonight.

The title comes from the name of a city in an alternate reality, which a couple kids slip into. Un Lun Dun. Un-London. Get it?

The world has other alternacities, of course. Parisn't, No York, Helsunki, Hong Gone.

The contest:

So, what's the name of your alternaplace, of the city you live in, or your neighbourhood, or your hometown, or where you went to school, or where you are right now (it must be a place you have a personal connection with)?

The prize:

The commenter with the cleverest (or silliest, or weirdest) response (as judged by me, probably) will receive my review copy (previously read by me; like new!) of Bang Crunch (really, it's worth reading), by Neil Smith, signed by the author earlier this evening (secondary contest: guess how many glasses of wine I had at the book launch). (International responses are both welcome and eligible. Contest closes February 3, midnight EST.)

Me? I live in Montsurreal.

One of the books I've been most looking forward to this winter is the new novel by China Miéville, this time writing for young adults. Un Lun Dun is set to hit store shelves February 13, but I'll be tucking into my review copy tonight.

The title comes from the name of a city in an alternate reality, which a couple kids slip into. Un Lun Dun. Un-London. Get it?

The world has other alternacities, of course. Parisn't, No York, Helsunki, Hong Gone.

The contest:

So, what's the name of your alternaplace, of the city you live in, or your neighbourhood, or your hometown, or where you went to school, or where you are right now (it must be a place you have a personal connection with)?

The prize:

The commenter with the cleverest (or silliest, or weirdest) response (as judged by me, probably) will receive my review copy (previously read by me; like new!) of Bang Crunch (really, it's worth reading), by Neil Smith, signed by the author earlier this evening (secondary contest: guess how many glasses of wine I had at the book launch). (International responses are both welcome and eligible. Contest closes February 3, midnight EST.)

Me? I live in Montsurreal.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)