Wolf Haas is the author of a

series of comic crime novels featuring private investigator Simon Brenner, a former cop. Three of them are now

available in English, and a fourth is on its way. (The English publications are not in the order of their original release.) I saw Haas yesterday evening at the

Blue Metropolis Literary Festival.

Haas is Austrian, and so is his German. "If it sounds weird, sounds wrong, it's a good translation." He apologizes for his English, but explains that when he reads in German, he also has to apologize for his German: "It's not real German, it's more like the nightmare of German." There is not only one kind of German.

His writing style is unique. It's very much like spoken language, lively, verbal tics and all. He writes the way he does because he likes the sound of it. (And it makes for very compelling reading.)

He likes reading in English because it's as if he's reading a book someone else wrote. He is distanced from the words; the words come as a surprise and he's not as judgemental of them as if he were reading them in his own language.

On top of which, in English they sound more like a real whodunit. He seems to romanticize the American crime thriller. As I riffle through scads of Scandinavian bestsellers in my head, I realize he means the hard-boiled, noir tradition.

In his view (and mine) it's the

narrator of these books who's the main character, not the detective.

There's an attempt to explain the detective Simon Brenner to those who have not read any of the books. The interviewer likes the Columbo analogy; I don't. Brenner may have a common-man appeal about him, but he's not that clever. A bit oafish; not exactly clumsy, but intellectually sloppy. He never controls a situation; things happen to him.

Haas describes Brenner as a dinosaur of a man, an old-fashioned stereotype, only he tried to make him more likeable. Like his uncles. The kind of man who has to appear strong, tough; says little, but drinks a lot. Remember, Brenner's an ex-cop, and all-round fuck-up. "He tries to think, but he's too tired."

So how does he solve anything then (or does he)? "I don't want to be rude in a foreign language, but that's when the narrator kicks his ass."

While some of his writing has a basis in reality, Haas admits that much of it is pure fantasy; for example, Brenner's hometown is a real village, but Haas has never been there. Haas travels to promote his books, of course, and he discusses how those experiences are creeping into his books. But he's wary of opening his mind too far; his books are, after all, about small villages with narrow-minded people.

When did Wolf Haas realize he needed to write? He sets the interviewer straight: "I do not need to write. I

want to write." Being a writer was a more attractive alternative to having a proper job, though not so viable in the beginning. What he learned from his days writing advertising copy: when you have an idea, you have to stick with it, run with it past the point of no return. He confesses that it's somewhat embarrassing to write crime stories — it's ridiculous.

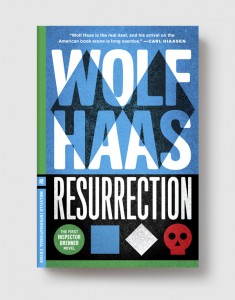

I picked up a copy of

Resurrection and he signed it for me. We even managed some (very) small talk. I asked him whether he reads a lot of crime novels, does he have a favourite crime writer, but it turns out, no, he reads maybe 2 or 3 a year, he likes reading all kind of things, "even poetry" (and it sounded to me a little like a line). Lovely man, shy, a bit nervous and awkward — real, with things to say.

Read Wolf Haas.