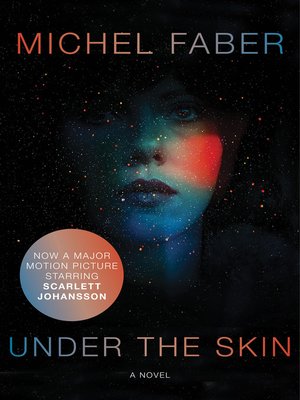

"You know," he said, almost dreamily, "I sometimes think that the only things really worth talking about are the things people absolutely refuse to discuss."I read Michel Faber's Under the Skin over a month ago, but I put off writing about it, wanting to see the film adaptation. Now I'm at a loss — they are so completely different, yet also compelling and weird. They're both also nigh impossible to talk about without giving anything away.

"Yes," snapped Isserley, "like why some people are born into a life of lazing around and philosophizing, and others are shoved into a hole and told to fucking get busy."

The weight, weightiness, of them comes out of the title. We're immediately invited to question: What's under Isserley's skin? What's under Scarlet Johansson's skin? The character in both the novel and the film is somehow off, out of place, other.

The only thing seemingly clear from the outset is that we're dealing with a female predator. In the film this is highly sexualized, because ScarJo; in the novel, Isserley is weird-looking, but men are distracted by her massive breasts, because men. But she's a very good predator; she studies her prey, their habits, and their environment intensely.

The film does a great job of focusing on the predation. The novel goes far beyond female-male relations (not that the film does just that) to cover a lot more territory, a whole other culture, in fact.

Under the Skin is also very much about the relationship between hunter and hunted. What's under the skin of her victims, anyway? What constitutes our humanity?

The thing about vodsels was, people who knew nothing whatsoever about them were apt to misunderstand them terribly. There was always the tendency to anthropomorphize. A vodsel might do something which resembled a human action; it might make a sound analogous with human distress, or make a gesture analogous with human supplication, and that made the ignorant observer jump to conclusions.It's the sort of talk that could turn you vegetarian. The novel might also be read as a warning about the dangers of disturbing an ecosystem ("A few drops of chemical soap into such a vast reservoir of natural purity wouldn't have much effect, surely?"). The problems of overhunting. How economics factors into our moral choices.

In the end, though, vodsels couldn't do any of the things that really defined a human being. They couldn't siuwil, they couldn't mesnishtil, they had no concept of slan. In their brutishness, they'd never evolved to use hunshur; their communities were so rudimentary that hississins did not exist; nor did these creatures seem to see any need for chail, or even chailsinn.

And, when you looked into their glazed little eyes, you could understand why.

If you were looking clearly, that is.

So, that's why it was better that Amlis Vess didn't know that the vodsels had a language.

Most reviews of the novel give away the story, and that's okay in the sense that that's not really what the book is about. However, I really loved the discovery of the story as the novel unfolded. It changed tack several times; it started off as a thriller, turned scifi, took a romantic twist, and mused on socioeconomic structures, before finally settling into an existential introspection — the problem of otherness and the impossibility of genuine communication.

That's what lying had done to the world. All the lying that people had been doing since the dawn of time, all the lying they were doing still. The price everyone paid for it was the death of trust. It meant that no two humans, however innocent they might be, could ever approach one another like two animals. Civilization!Reviews (with spoilers)

LitMed

New York Times

Excerpt.

No comments:

Post a Comment