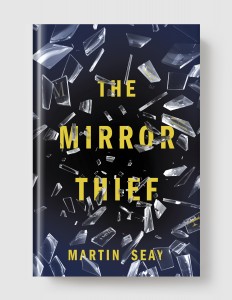

As he reads, his eyes graze each poem's lines like a needle over an LP's grooves, atomizing them into letters, reassembling them into uniform arcades. What he's looking for is a key: a gap in the book's mask, a loose thread to unravel its veil. He tries tricks to find new openings — reading sideways, reading upsidedown, reading whitespace instead of text — but the works always close ranks like tiles in a mosaic, like crooks in a lineup, and mock him with their blithe expressions. The usual suspects.I've begun reading The Mirror Thief, by Martin Seay. The first page didn't feel right, maybe not my cup of tea after all. The first major section is set in Vegas. But before I knew it, I couldn't stop reading. The focus is on Stanley, everybody's looking for him, trying to discover his whereabouts. The second major section takes us to California, back in time to Stanley's youth. This didn't feel right either, the change in locale and tone, another cup of tea that isn't mine. But I am learning that all Stanley's movements centre around a book.

The Mirror Thief is a book about a book called The Mirror Thief. It is starting to feel like a booklover's book.

(This book feels overly masuline. I don't know what I mean by that. I think that's why it doesn't feel right. Maybe it's just the wrong time and place for me to be reading this book. I'm enjoying it, but something just doesn't feel right.)

It is difficult, but probably necessary, to remember that books always know more then their authors do. They are always wiser. This is strange to say, but it's true. Once they are in the world, they develop their own peculiar ideas.

No comments:

Post a Comment