The Other believes that there is a Great and Secret Knowledge hidden somewhere in the World that will grant us enormous powers once we have discovered it. What this Knowledge consists of he is not entirely sure, but at various times he has suggested that it might include the following:

- vanquishing Death and becoming immortal

- learning by a process of telepathy what other people are thinking

- transforming ourselves into eagles and flying through the Air

- transforming ourselves into fish and swimming through the Tides

- moving objects using only our thoughts

- snuffing out and reigniting the Sun and Stars

- dominating lesser intellects and bending them to our will

Piranesi, by Susanna Clark, is a mesmerizing enchantment.

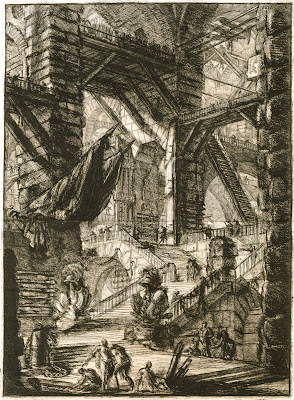

Piranesi, as he is called by the Other, lives in the House, explores the House, documents the House, loves the House. "The Beauty of the House is immeasurable; its Kindness infinite." The House is a labyrinth (the First Vestibule contains eight massive Statues of Minotaurs), an endless dilapidated mansion (many ceilings are cracked if not collapsed, particularly in the Derelict Halls of the East), perhaps a kind of prison.

Piranesi struggles to survive, collecting rainwater and trapping fish, drying out skins and seaweed. He tracks the tides. There appears to be no exit, but he never questions the Other's comings and goings, or how he manages to procure for him over the years a cheese and ham sandwich, a new pair of shoes, or an endless supply of multivitamins.

I write down what I observe in my notebooks. I do this for two reasons. The first is that Writing inculcates habits of precision and carefulness. The second is to preserve whatever knowledge I possess for you, the Sixteenth Person.

While Piranesi is systematic in applying the principles of rationality to every situation he encounters, there is naivete in his interpretations and gaps in his understanding.

The puzzle of the House is initially its geography, but for the reader it quickly becomes the mystery of Piranesi's being there and piecing together scraps of journals to formulate a theory of his relationship with the outside world.I went to the Eighteenth North-Western Hall and had a long drink of water. It was delicious and refreshing (it had been a Cloud only hours before).

This realisation — the realisation of the Insignificance of the Knowledge — came to me in the form of a Revelation. What I mean by this is that I knew it to be true before I understood why or what steps had led me there. When I tried to retrace those steps my mind kept returning to the image of the One-Hundred-and-Ninety-Second Western Hall in the Moonlight, to its Beauty, to its deep sense of Calm, to the reverent looks on the Faces of the Statues as they turned (or seemed to turn) towards the Moon. I realised that the search for the Knowledge has encouraged us to think of the House as if it were a sort of riddle to be unravelled, a text to be interpreted, and that if ever we discover the Knowledge, then it will be as if the Value has been wrested from the House and all that remains will be mere scenery.

The sight of the One-Hundred-and-Ninety-Second Western Hall in the Moonlight made me see how ridiculous that is. The House is valuable because it is the House. It is enough in and of Itself. It is not the means to an end.

The fragments of information begin to position us in relation to our current physical world, late twentieth century to present day, and introduce us to a group of "transgressive thinkers." We follow Piranesi's train of thought as he pursues cross-references to journal entries that include passages copied from books and lecture notes (and a timey-wimey shoutout), addressing the nature of Ancient Man and the Theory of Other Worlds.

"Once, men and women were able to turn themselves into eagles and fly immense distances. They communed with rivers and mountains and received wisdom from them. They felt the turning of the stars inside their own minds. My contemporaries did not understand this. They were all enamored with the idea of progress and believed that whatever was new must be superior to what was old. And its merit was a function of chronology! But it seemed to me that the wisdom of the ancients could not have simply vanished. Nothing simply vanishes. It's not actually possible. I pictured it as a sort of energy flowing out of the world and I thought that this energy must be going somewhere. That was when I realised that there must be other places, other worlds. And so I set myself to find them."

It's tempting to read the House as a state of Piranesi's mind. It's somewhat more horrific than that, but it remains beautiful.

Perhaps that is what it is like being with other people. Perhaps even people you like and admire immensely can make you see the World in ways you would rather not.

Piranesi is a meditation on how we create meaning. Trapped with himself, really, Piranesi struggles with the nature of memory and his relationship to the past to define his place in the world. His days are chores and rituals and observations.

This is the most immersive novel I've read in a very long time (and I can easily imagine it as a virtual reality experience). I could spend a lifetime exploring the halls and the statues, attuning myself to the rhythm of the House, gathering clues to its nature.

Excerpts

When the Moon rose in the Third Northern Hall I went to the Ninth Vestibule

A list of all the people who have ever lived and what is known of them

I retrieve the scraps of paper from the Eighty-Eighth Western Hall

I question the Other

"We shan't meet again."

"Then, sir, may your Paths be safe," I said, "your Floors unbroken and may the House fill your eyes with Beauty."

No comments:

Post a Comment