I am drowning in colour.

I am drowning in colour.The Street of Crocodiles, by Bruno Schulz, is under discussion at MetaxuCafé by the Slaves of Golconda.

The novel, or collection of stories, was originally called Cinnamon Shops, after one of the stories therein. "I used to call them cinnamon shops because of the dark paneling of their walls."

Since I first started my hunt for a copy in Polish, I've been rather obsessed with the matter of the title. Whereas Cinnamon Shops is breathtakingly fantastic, the Street of Crocodiles is bleak, bordering on grotesque. The two stories are so opposite in tone; to give the title of one over the other to the collection seems to me to impose a mood on the reader. I'm genuinely puzzled by the title switch.

Cinnamon Shops is truly full of wonder:

These truly noble shops, open late at night, have always been the objects of my ardent interest. Dimly lit, their dark and solemn interiors were redolent of the smell of paint, varnish, and incense; of the aroma of distant countries an rare commodities. You could find in them Bengal lights, magic boxes, the stamps of long-forgotten countries, Chinese decals, indigo, calaphony from Malabar, the eggs of exotic insects, parrots, toucans, live salamanders and basilisks, mandrake roots, mechanical toys from Nuremberg, homunculi in jars, microscopes, binoculars, and, most especially, strange and rare books, old folio volumes full of astonishing engravings and amazing stories.

I remember those old dignified merchants who served their customers with downcast eyes, in discreet silence, and who were full of wisdom and tolerance for their customers' most secret whims. But most of all, I remember a bookshop in which I once glanced at some rare and forbidden pamphlets, the publications of secret societies lifting the veil on tantalizing and unknown mysteries.

I spent much of the last week trying to establish the right mood by which to read this. Dipping into my collection of Polish folk songs, and old Polish crooners. Skimming through early 20th century poetry, the program notes from some of the plays I'd seen, my course notes on Młoda Polska and modernism.

I spent much of the last week trying to establish the right mood by which to read this. Dipping into my collection of Polish folk songs, and old Polish crooners. Skimming through early 20th century poetry, the program notes from some of the plays I'd seen, my course notes on Młoda Polska and modernism.(I discovered the existence of what might be the perfect mood music, but it won't be in my possession for weeks yet (I tell myself it's better suited to Schulz's other book anyway). Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass: A Tribute to Bruno Schulz, the Cracow Klezmer Band plays the music of John Zorn. John freakin' Zorn!)

I circled around Schulz and 1934, listened to multiple renditions of the suicide tango, never quite getting the book-reading ambience exactly right. I have a sense of what came before Schulz (Witkacy), what came after (Gombrowicz), and what happened alongside, but Schulz himself is unique.

There's little information available on Schultz, biographical or critical. (Also, I am mystified to discover that volume 3 of Witold Gombrowicz's Diary, the volume that details his friendship with Schulz, is missing from my shelves.)

In the end, there was nothing for it but for Bruno Schulz to create his own mood.

My response — uninformed, the one from my gut — to this book: I am drowning in colour, and light, with shadows. It is overwhelmingly visual.

From the first page alone: "the blinding white heat," "dizzy with light," "blazing with sunshine," "golden pears,"luminous mornings," "the flames of day," "the colorful beauty of the sun," "shiny pink cherries," "transparent skins," "mysterious black morellos," "golden pulp." And it goes on. Everything bathed in melting gold, drenched with honey. It's an assault of light and heat. As I become acclimatized to the mid-summer, the colours begin to appear darker, richer: velvet bruises, amber, heavy black sleep. Then the birds: splashes of crimson, strips of sapphire, verdigris, silver; thick flakes of azure, of peacock and parrot green, of metallic sparkle. The yellow-white light, the bright night of winter offers up cinnamon and violets.

The stories have little plot, but they are full-colour sketches. They are connected by time, place, character. They feel like a grown-up reaching back in time to his childhood, for a memory grounded in his visual sense but which keeps shape-shifting.

The stories have little plot, but they are full-colour sketches. They are connected by time, place, character. They feel like a grown-up reaching back in time to his childhood, for a memory grounded in his visual sense but which keeps shape-shifting.Schulz himself states that:

"It is an autobiography — or rather, a genealogy — of the spirit . . . since it reveals the spirit's pedigree back to those depths where it merges with mythology, where it becomes lost in mythological ravings. I have always felt that the roots of the individual mind, if followed far enough down, would lose themselves in some mythic lair. This is the final depth beyond which one can no longer go."

I find Schulz in his stories puts into words what I've seen in the quintessentially Polish visual art that preceded him. (Ironically, I find that his own artwork is of a very different school, a little bit grotesque, cartoonish. I am unable to reconcile his own drawings to his words.)

I find Schulz in his stories puts into words what I've seen in the quintessentially Polish visual art that preceded him. (Ironically, I find that his own artwork is of a very different school, a little bit grotesque, cartoonish. I am unable to reconcile his own drawings to his words.)The first visual reference I made was to Wyspianski (1869–1907), likely most recognized as a playwright, whose murals and stained glass flood the Franciscan church in Krakow. It's positively hallucinogenic, enormous flowering vines crawling the pews and walls. I'd hate to attend mass on drugs — it smells of violets everywhere — for fear the sunflowers would bite my head off.

Schulz would not have met Wyspianski, but there's no doubt that he would've been familiar with his work.

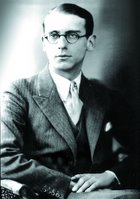

Witkacy (1885–1939), an artist of many talents, also perhaps best known as a playwright, promoted Bruno Schulz, befriended him, corresponded with him.

All these artworks preceded the publication of Cinnamon Shops by some dozen or more years, but I see them as part of the same tradition.