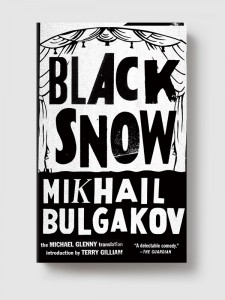

Why do so many Russian writers need to make their protagonist a victim or pain-bearer? Why this fixation with self-flagellation? With guilt?— from Terry Gilliam's introduction to Black Snow, by Mikhail Bulgakov.

My theory — based on absolutely no research whatsoever — starts with mud. Thick, sucking, up-to-your-knees mud. Centuries of it. Add millions of serfs all labouring away, mired deep in the relentless, endless mud of Russia. Lives worn away by the yoke of oppressive landowners. Throw into the mix long, dark, dismally cold winter. Pile on the gloomy weight of the church. Voilà! The only hope of survival is to admit your guilt and accept punishment for the unknown sin that landed you in this miserable existence. A resigned acknowledgement of your own responsibility. A spiritual masochism.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Mired deep in the relentless, endless mud of Russia

Labels:

Mikhail Bulgakov,

Terry Gilliam

Sunday, November 24, 2013

What is this world?

So I make one phone call, and just like that, we're eating pizza at 6:30. What is this world? You tap seven abstract figures onto a piece of plastic thin as a billfold, hold that plastic device to your head, use your lungs and vocal cords to indicate more abstractions, and in thirty minutes, a buy pulls up in a 2,000-pound machine made on an island on the other side of the world, fueled by viscous liquid made from the rotting corpses of dead organisms pulled from the desert on yet another side of the world and you give this man a few sheets of green paper representing the abstract wealth of your home nation, and he gives you a perfectly reasonable facsimile of one of the staples of the diet of a people from yet another faraway nation.

And the mushrooms are fresh.

— from The Financial Lives of the Poets, by Jess Walter.

This is Matt. He's forty-six, sleep-deprived, and somewhat stoned, having recently made the sound life decision to — seeing as he was recently laid off, they're foreclosing on his house next week, and he suspects his wife is cheating — become a drug dealer. Only that's not really working out either. Matt's world is unravelling, and now his mind is too.

Labels:

Jess Walter

Friday, November 22, 2013

Living poetically

We saw the circus last weekend.

Cirkopolis

C'est la quête identitaire d'un travailleur solitaire.

C'est l'obsession de retrouver son âme d'enfant.

C'est le parcours initiatique d'un clown

qui par sa poésie va changer son environnement.

A little purer than the now seemingly garish and bombastic Cirque du Soleil.

Cirkopolis

C'est la quête identitaire d'un travailleur solitaire.

C'est l'obsession de retrouver son âme d'enfant.

C'est le parcours initiatique d'un clown

qui par sa poésie va changer son environnement.

A little purer than the now seemingly garish and bombastic Cirque du Soleil.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

One great thing

There are lots of great things about Helena, but when the Nivea commercial came on while we were watching TV, I had to ask her, what did she think was one great thing about herself.

"I like to talk," she said without hesitation.

"No, wait. I like to think. Yeah. A lot. I really like to think."

(I love her to bits!)

Happy birthday, kid!

"I like to talk," she said without hesitation.

"No, wait. I like to think. Yeah. A lot. I really like to think."

(I love her to bits!)

Happy birthday, kid!

Labels:

Helena

Monday, November 18, 2013

A Doris Lessing notebook

The Lessing Woman:

I was being domestic this morning, cleaning. For some reason I opened a drawer I almost never open. In it are some old work contracts, an address book, and, for some reason, two books that I keep separate from all the other hundreds of books in the house: Kwiaty Polskie, a volume of poetry by Julian Tuwim, in Polish; and Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook. I took out the Notebook and fondled it; I like the feel of my edition, I like the look of all its not quite gold-hued lines. Not an hour later, in a meeting with the rep for my daughter's education fund, my phone alerted me that Doris Lessing had died.

My first Lessing book was The Marriages between Zones Three, Four, and Five, in a course on dystopian fiction, when I was 18. I've been reading Lessing regularly ever since.

The Making of the Representative for Planet 8, Prelude. Music, Philip Glass; libretto, Doris Lessing.

Lectures

Nobel lecture

Monique Beudert Memorial Lecture

Obituaries

Margaret Atwood, The Guardian: "She was political in the most basic sense."

Lorna Sage, The Guardian: "Commitment was one of the things from which she weaned herself away."

Lisa Allardice, The Guardian: "Lessing seemed to have an almost uncanny genius for pre-empting problems or social change."

Maev Kennedy, The Guardian: "Few writers have as broad a range of subject and sympathy."

Boyd Tonkin, The Independent: "Crucially, she also shook the dust of successive movements, styles and ideologies from her ever-restless feet: communism; feminism; psychoanalysis; social realism."

Charlie Jane Anders, io9: "Lessing was a master of combining characters with rich inner lives with a general hint of strangeness in the world around them."

Helen T. Verongos, The New York Times: "She divorced herself from all 'isms'."

Vicki Barker, NPR: "She was a campaigner against racism, a lover, an ardent communist, and a serial rescuer of cats."

Gaby Wood, The Telegraph: "How many women can be said to have been thought of as an Angry Young Man?"

Elaine Showalter, The Washington Post: "Cantankerous, irascible, outspoken, she thrived on controversy and outrage."

Excerpts

The Cleft

"Dialogue"

"How I Finally Lost My Heart"

On Cats

"Our Friend Judith"

Commentary

The Fifth Child

The Golden Notebook

The Good Terrorist

The Grandmothers

Mara and Dann

Memoirs of a Survivor

The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog

A quick review of this blog shows that I've managed to mention Doris Lessing while writing about Jim Crace, Jeanette Winterson, Keith Scribner, Lionel Shriver, Allen Kurzweil, China Miéville, Penelope Mortimer. She is a baseline. (And of there writers, I think only Miéville is in the same league as her, of the same ilk.)

Thank you, Doris Lessing, for introducing me to Patrick Hamilton, George Gissing, Anna Kavan. And for planting the idea that Charles Dickens would be good in bed (Tolstoy, not so much).

So I cannot say that Doris Lessing changed me, but she helped me recognize that I was ready to be changed, on several occasions.

Fans of British Novelist Doris Lessing talk about a composite character called the Lessing Woman in much the same way as people once talked about the Hemingway Man. The Lessing Woman is a formidable female. She hasn't been to a university but she has read everything and remembers it. Her ideals are high and unsullied. She works (or has worked) at lost political causes. Although she loathes marriage, she gamely raises children and endures domestic woes. She cooks well, keeps a spotless house (except when depressed) and does excellent writing, research or secretarial work. She is any man's moral and intellectual superior, and she rarely hesitates to tell him so.

I was being domestic this morning, cleaning. For some reason I opened a drawer I almost never open. In it are some old work contracts, an address book, and, for some reason, two books that I keep separate from all the other hundreds of books in the house: Kwiaty Polskie, a volume of poetry by Julian Tuwim, in Polish; and Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook. I took out the Notebook and fondled it; I like the feel of my edition, I like the look of all its not quite gold-hued lines. Not an hour later, in a meeting with the rep for my daughter's education fund, my phone alerted me that Doris Lessing had died.

My first Lessing book was The Marriages between Zones Three, Four, and Five, in a course on dystopian fiction, when I was 18. I've been reading Lessing regularly ever since.

The Making of the Representative for Planet 8, Prelude. Music, Philip Glass; libretto, Doris Lessing.

Lectures

Nobel lecture

Monique Beudert Memorial Lecture

Obituaries

Margaret Atwood, The Guardian: "She was political in the most basic sense."

Lorna Sage, The Guardian: "Commitment was one of the things from which she weaned herself away."

Lisa Allardice, The Guardian: "Lessing seemed to have an almost uncanny genius for pre-empting problems or social change."

Maev Kennedy, The Guardian: "Few writers have as broad a range of subject and sympathy."

Boyd Tonkin, The Independent: "Crucially, she also shook the dust of successive movements, styles and ideologies from her ever-restless feet: communism; feminism; psychoanalysis; social realism."

Charlie Jane Anders, io9: "Lessing was a master of combining characters with rich inner lives with a general hint of strangeness in the world around them."

Helen T. Verongos, The New York Times: "She divorced herself from all 'isms'."

Vicki Barker, NPR: "She was a campaigner against racism, a lover, an ardent communist, and a serial rescuer of cats."

Gaby Wood, The Telegraph: "How many women can be said to have been thought of as an Angry Young Man?"

Elaine Showalter, The Washington Post: "Cantankerous, irascible, outspoken, she thrived on controversy and outrage."

Excerpts

The Cleft

"Dialogue"

"How I Finally Lost My Heart"

On Cats

"Our Friend Judith"

Commentary

The Fifth Child

The Golden Notebook

The Good Terrorist

The Grandmothers

Mara and Dann

Memoirs of a Survivor

The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog

A quick review of this blog shows that I've managed to mention Doris Lessing while writing about Jim Crace, Jeanette Winterson, Keith Scribner, Lionel Shriver, Allen Kurzweil, China Miéville, Penelope Mortimer. She is a baseline. (And of there writers, I think only Miéville is in the same league as her, of the same ilk.)

Thank you, Doris Lessing, for introducing me to Patrick Hamilton, George Gissing, Anna Kavan. And for planting the idea that Charles Dickens would be good in bed (Tolstoy, not so much).

I do not believe that one can be changed by a book (or by a person) unless there is already something present, latent or in embryo, ready to be changed. Books have influenced me all my life. I could say as an autodidact — a condition that has advantages and disadvantages — that books have made me what I am. But it is hard to say of this book or that one: it changed me. How about War and Peace? Fathers and Sons? The Idiot? The Scarlet and the Black? Remembrance of Things Past? But now they all seem dazzling stages in a long voyage of discovery, which continues.

So I cannot say that Doris Lessing changed me, but she helped me recognize that I was ready to be changed, on several occasions.

Labels:

Doris Lessing

Saturday, November 16, 2013

The Zola project

I am enthralled by The Paradise. This television series pushes all the right buttons for me, though I can't identify them all. Music is one positive factor, and the beautiful people are another. For some reason I find the department store setting fascinating. Exquisite production value, fine acting, etc., but why I should be so enamored of this program while others leave me cold (ahem, Downton Abbey) is due to some ineffable je ne sais quoi.

(I'm watching on PBS Masterpiece Theater and we're nearing the end of season 1, but I've just discovered that most of the series is available on YouTube. I expect I'll be binging on season 2 before Christmas.)

The Paradise is based on Émile Zola's Au Bonheur des Dames, the eleventh novel in his 20-volume Rougon-Macquart series. The television program has transposed the story from Paris to somewhere in northeast England. Of course, this leaves me wondering how much else has been changed. And what better way to find out than to read the source material for myself?

Meanwhile, my other half has been reading up on L'Assommoir, another novel in that series, after we were speculating about the origin of the name of a local bar that goes by that appellation. And he's become somewhat obsessed with Zola's concept.

The Rougon-Macquart cycle follows the life of a family during the Second French Empire. It includes a couple of Zola's best known works: Nana (which I in fact read, about 25 years ago) and Germinal, and lo they are interconnected.

In Différences entre Balzac et moi, Zola noted:

The challenge then, for me and my other: to read the whole Rougon-Macquart cycle. Also, to read it in French. (This may take years.)

I will be following Zola's own recommended reading order with the following exception: I will pick up Au Bonheur des Dames first. The fact that I have some familiarity now with the story should help ease me into the language. Plus, I want all my pressing questions answered.

(I'm watching on PBS Masterpiece Theater and we're nearing the end of season 1, but I've just discovered that most of the series is available on YouTube. I expect I'll be binging on season 2 before Christmas.)

The Paradise is based on Émile Zola's Au Bonheur des Dames, the eleventh novel in his 20-volume Rougon-Macquart series. The television program has transposed the story from Paris to somewhere in northeast England. Of course, this leaves me wondering how much else has been changed. And what better way to find out than to read the source material for myself?

Meanwhile, my other half has been reading up on L'Assommoir, another novel in that series, after we were speculating about the origin of the name of a local bar that goes by that appellation. And he's become somewhat obsessed with Zola's concept.

The Rougon-Macquart cycle follows the life of a family during the Second French Empire. It includes a couple of Zola's best known works: Nana (which I in fact read, about 25 years ago) and Germinal, and lo they are interconnected.

In Différences entre Balzac et moi, Zola noted:

In one word, his work wants to be the mirror of the contemporary society. My work, mine, will be something else entirely. The scope will be narrower. I don't want to describe the contemporary society, but a single family, showing how the race is modified by the environment. (...) My big task is to be strictly naturalist, strictly physiologist.

The challenge then, for me and my other: to read the whole Rougon-Macquart cycle. Also, to read it in French. (This may take years.)

I will be following Zola's own recommended reading order with the following exception: I will pick up Au Bonheur des Dames first. The fact that I have some familiarity now with the story should help ease me into the language. Plus, I want all my pressing questions answered.

Labels:

Émile Zola,

French literature,

reading challenge,

television

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

What is a poet?

What is a poet? An unhappy person who conceals profound anguish in his heart but whose lips are so formed that as sighs and cries pass over them they sound like beautiful music. It is with him as with the poor wretches in Phalaris's bronze bull, who were slowly tortured over a slow fire; their screams could not reach the tyrant's ears to terrify him; to him they sounded like sweet music. And people crowd around the poet and say to him, "Sing again soon" — in other words, may new sufferings torture your soul, and may your lips continue to be formed as before, because your screams would only alarm us, but the music is charming. And the reviewers step up and say, "That is right; so it must be according to the rules of esthetics." Now of course a reviewer resembles a poet to a hair, except that he does not have the anguish in his heart, or the music on his lips. Therefore, I would rather be a swineherd out on Amager and be understood by swine than be a poet and be misunderstood by people.— from "Diapsalmata," in Either/Or, by Søren Kierkegaard.

This is a very strange and disjointed text, mostly dwelling on Kierkegaard's (self-termed) "depression." He sounds overly dramatic, and very much like those German Romantics he rails against.

I have, I believe, the courage to doubt everything; I have, I believe, the courage to fight against everything; but I do not have the courage to acknowledge anything, the courage to possess, to own, anything. Most people complain that the world is so prosaic that things do not go in life as in the novel, where opportunity is always so favorable. I complain that in life it is not as in the novel, where one has hardhearted fathers and nisses and trolls to battle, and enchanted princesses to free. What are all such adversaries together compared with the pale, bloodless, tenacious-of-life nocturnal forms with which I battle and to which I myself give life and existence.

How self-indulgent.

I was completely unprepared for this. It seems that after having defended his thesis (The Concept of Irony), Kierkegaard threw all notions of structure and form to the wind, one big middle finger to the Man, his traditions and institutions. This strikes me as a little at odds with his being a Christian theologian, but what do I know. (Maybe we'll cover this issue later in the course.) To Kierkegaard's credit, he practiced what he preached, practiced irony and found his own subjective truth.

It's pages upon pages of aphorisms concerning death, cereal, erotic love, Mozart, boredom, salmon, Sunday afternoons. It begs to be parodied. And it's wildly beautiful.

This is the way, I suppose, that the world will be destroyed — amid the universal hilarity of wits and wags who think it is all a joke.

Labels:

philosophy,

poetry,

Søren Kierkegaard

Monday, November 11, 2013

No genuinely human life is possible without irony

In our age there has been much talk about the importance of doubt for science and scholarship, but what doubt is to science, irony is to personal life. Just as scientists maintain that there is no true science without doubt, so it may be maintained with the same right that no genuinely human life is possible without irony. Irony limits, finitizes, and circumscribes and thereby yields truth, actuality, content; it disciplines and punishes and thereby yields balance and consistency. Irony is a disciplinarian feared only by those who do not know it but loved by those who do. Anyone who does not understand irony at all, who has no ear for its whispering, lacks eo ipso [precisely thereby] what could be called the absolute beginning of personal life; he lacks what momentarily is indispensable for personal life; he lacks the bath of regeneration and rejuvenation, irony's baptism of purification that rescues the soul from having its life in finitude even though it is living energetically and robustly in it. He does not know the refreshment and strengthening that come with undressing when the air gets too hot and heavy and diving into the sea of irony, not in order to stay there, of course, but in order to come out healthy, happy, and buoyant and to dress again.

Therefore, if at times someone is heard talking with great superiority about irony in the infinite striving in which it runs wild, one may certainly agree with him, but insofar as he does not perceive the infinity that moves in irony, he stands not above but below irony. So it is always wherever we disregard the dialectic of life.

— from The Concept of Irony, by Søren Kierkegaard.

(Which is weirdly both unscholarly yet pretentious.)

Labels:

philosophy,

Søren Kierkegaard

Saturday, November 09, 2013

Subject to the profoundest doubt

Written in 1963, The Group, by Mary McCarthy, follows the intertwined lives of a set of Vassar graduates, class of '33.

I only became aware of this book because in season 3 of Mad Men, Betty slips into the bath with it. Generally regarded as an early feminist novel, The Group this year celebrated the 50th anniversary of its publication, though it is set several decades earlier still.

The book could equally be regarded as a set of intertwined short stories. Each chapter focuses on one member of the group, and we hear about the rest of the group from that perspective. The chapters could for the most part stand on their own, but they are more powerful within the context of the group.

Kay:

Helena:

Norine is an outsider, not a member of the group, but after graduation she is a neighbour of Kay's and her life also becomes caught up in the group's fate:

And:

Chapter two covers Dottie's deflowering, and even while I was thinking, "Dottie, don't do it," and "The dialogue is ridiculous," and "Girls in 1933, huh", and "You're overthinking it," there was some laughing too, it also managed to make me blush. I may not have read 50 Shades, but I'm no prude, and this event was unabashedly, genuinely, beautifully female.

Is this book still relevant today? I want to say yes, but if I'm to be honest with you, I'll have to stammer that, well, it's not irrelevant, anyway. Certainly it was noteworthy on its release in 1963, but women have changed. Society and social expectations have not changed as much as they ought, and I fear today's women may neither recognize nor heed the warnings — about love, marriage, motherhood, parenting, career, gender equality, life — carried in The Group's gentle observations of what becomes of college girls.

See also:

Vassar, Unzipped!, by Laura Jacobs, Vanity Fair, July 2013.

The Mary McCarthy Case, by Norman Mailer, The New York Review of Books, October 1963.

I only became aware of this book because in season 3 of Mad Men, Betty slips into the bath with it. Generally regarded as an early feminist novel, The Group this year celebrated the 50th anniversary of its publication, though it is set several decades earlier still.

The book could equally be regarded as a set of intertwined short stories. Each chapter focuses on one member of the group, and we hear about the rest of the group from that perspective. The chapters could for the most part stand on their own, but they are more powerful within the context of the group.

Kay:

She had been amazingly altered, they felt, by a course in Animal Behaviour she taken with old Miss Washburn who had left her brain in her will to Science) during their junior year. This and her work with Hallie Flanagan in Dramatic Production had changed her from a shy, pretty, somewhat heavy Western girl with black lustrous curly hair and a wild-rose complexion, active in hockey, in the choir, given to large tight brassieres and copious menstruations, into a thin, hard-driving, authoritative young woman, dressed in dungarees, sweat shirt, and sneakers, with smears of paint in her unwashed hair, tobacco stains on her fingers, talking airily of "Hallie" and "Lester," Hallie's assistant, of flats and stippling, of oestrum and nymphomania, calling her friends by their last names loudly — "Eastlake," "Renfrew," "MacAusland" — counseling premarital experiment and the scientific choice of a mate. Love, she said, was an illusion.

Helena:

Her mother's habit of stressing and underlining her words had undergone an odd mutation in being transmitted to Helena. Where Mrs. Davison stresses and emphasized, Helena inserted her words carefully between inverted commas, so that clauses, phrases, and even proper names, inflected, by her light voice, had the sound of being ironical quotations. While everything Mrs. Davison said seemed to carry with it a guarantee of authority, everything Helena said seems subject to the profoundest doubt.

Norine is an outsider, not a member of the group, but after graduation she is a neighbour of Kay's and her life also becomes caught up in the group's fate:

"All I knew that night was that I believed I something and couldn't express it, while your team believed in nothing but knew how to say it — in other men's words."

And:

Watching her, Helena granted Norine a certain animal vitality, and "earthiness" that was underscored, as if deliberately, by the dirt and squalor of the apartment. Bedding with her, Helena imagined, must be like rolling in a rich moldy compost of autumn leaves, crackling on the surface, like her voice, and underneath warm and sultry from the chemical process of decay.

Chapter two covers Dottie's deflowering, and even while I was thinking, "Dottie, don't do it," and "The dialogue is ridiculous," and "Girls in 1933, huh", and "You're overthinking it," there was some laughing too, it also managed to make me blush. I may not have read 50 Shades, but I'm no prude, and this event was unabashedly, genuinely, beautifully female.

Is this book still relevant today? I want to say yes, but if I'm to be honest with you, I'll have to stammer that, well, it's not irrelevant, anyway. Certainly it was noteworthy on its release in 1963, but women have changed. Society and social expectations have not changed as much as they ought, and I fear today's women may neither recognize nor heed the warnings — about love, marriage, motherhood, parenting, career, gender equality, life — carried in The Group's gentle observations of what becomes of college girls.

See also:

Vassar, Unzipped!, by Laura Jacobs, Vanity Fair, July 2013.

The Mary McCarthy Case, by Norman Mailer, The New York Review of Books, October 1963.

Labels:

Mad Men,

Mary McCarthy

Monday, November 04, 2013

The idea for which I am willing to live and die

What I really need is to be clear about what I am to do, not what I must know, except in the way knowledge must precede all actions. It is a question of understanding my own destiny, of seeing what the Deity really wants me to do; the thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die. And what use would it be in this respect if I were to discover a so-called objective truth, or if I worked my way through the philosophers' systems and were able to call them all to account on request, point out inconsistencies in every single circle? And what use would it be in that respect to be able work out a theory of the state, and put all the pieces from so many places into one whole, construct a world which, again, I myself did not inhabit but merely held up for others to see? What use would it be to be able to propound the meaning of Christianity, to explain many separate facts, if had no deeper meaning for myself and my life?

— from Journal AA:12, Søren Kierkegaard, 1835.

I haven't decided how I feel about Kierkegaard. This passage speaks to me, but even while saying, "Yes, Søren, I can totally relate," another part of me is saying, "Really? Just how old are you? Every college student goes through this shit, and most of us get over it." Though the sentiments are common and it could've been written by any kid, the above passage is oft-cited because it is from a philosopher's journal.

One fellow MOOC student recently accused another of having reduced Kierkegaard to the psychological realm; I'm not sure it's wrong to do so. Kierkegaard is whiny, lovelorn, and full of bitter resentment.

Meanwhile, I'm currently suffering from irony overload (Socratic and other), and yeah, still looking for an idea for which I am will to live and die.

Labels:

philosophy,

Søren Kierkegaard

Friday, November 01, 2013

Unhappy few mortals

I'm one of those unhappy few mortals that can't put down a novel till I know how it comes out. Words cast a spell on me. Even the worst words in the worst order.

— from The Group, by Mary McCarthy.

Labels:

Mary McCarthy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)