I have a lot of work, a big contract, to deal with over the coming weeks, so I'm off to a fine start in my procrastinating, oddly enough doing things other than blogging.

The next time I decide to refurbish a set of drawers, somebody, please, just kick me.

Helena hates her bedroom, or hates sleeping in it, or possibly simply prefers sleeping with us, although she's fairly articulate about what she likes in our bedroom — the colours, the bookshelves, the coziness — that I give credence to her disliking her room. I don't much like it either, but with its configuration and the furniture passed on to us from a relative, and our budget, there seemed little to do. Painting the walls was an option, is still an option, but the logistics of it are daunting. And I've always hated that furniture, white, with brass hardware and icky floral motif. So, in a flash of inspiration, we bought her a new bed around Christmas, and made plans, figuring some paint and sleek hardware would spruce up the drawers; we'll install a bookcase in the next couple weeks.

What seemed like a quick and easy way to bring life to Helena's bedroom, has cost a few bucks, about 6000 hours of labour, and endless grief. I have concluded that television decorating shows are fixed. It is beyond me how anyone could sand, clean, paint, and seal to an acceptable standard a couple apparently simple pieces of furniture but with weird nooks and crannies in an afternoon, let alone redo entire rooms. Not worst is Helena's insistence on helping, to which I stupidly respond, "OK," and which entails extra hours of fixing and cleaning up after when she's not looking. I have learned also that, although the sun is shining, it really isn't nearly warm enough to do any of this outside or even inside with the patio doors and windows open. So I'm cold, cranky, tired.

But it's almost done now, and I feel a little bit of pride in it, seeing a deep purple chest and night table with bright red rectangles of drawers in them, and seeing Helena take pride in her contribution to the project.

Meanwhile...

I am dying to finish A Canticle for Leibowitz (Walter M Miller Jr). I've been meaning to read it for some dozen years, so when I was offered a review copy of its reissue I accepted. I'm within spitting distance of the end now. I've been bringing it to bed with me every night this week, but I keep falling off to sleep a sleep of exhaustion.

I am not dying to finish reading Infinite Jest. I am, however, dying to fulfill my commitment to reading it. I just need to read something else first.

I have started The Color of a Dog Running Away, by Richard Gwyn — another review copy I couldn't pass up based on its description. The epigram for Part One is from Milan Kundera: "We can never know what to want, because, living only one life, we can neither compare it with our previous lives or perfect it in our lives to come." I read that and hear Daniel Day Lewis confirming, "There is no dress rehearsal for life." I have no idea what that means in the context of a novel about roof dwellers and religious cults, only what it means in the context of my own life. But it means something.

Other books I'm eying, which arrived this week after finally putting Christmas gift certificates to use:

The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas. The paperback arrived with the cover creased, slightly mangled, and while this niggles at me a little, I think I've finally grown to the point where I'm past caring enough to do anything about it beyond this little griping here and now. (Seriously, I think I've come to love books in a better way these last few years.) I know it will show lots of wear by the time I'm done with it.

The Messiah of Stockholm, Cynthia Ozick, acquisition of which was inspired by my recent introduction to Bruno Schulz via The Street of Crocodiles. Its story tracks Schulz's lost manuscript.

Doctor Who Files: Rose. Which isn't really for me. It seemed a good idea that Helena should have a memento of her hero. And it also seems a good idea that Helena should have something new to entertain her during the 7-hour car ride we'll be enduring Easter weekend. I've yet to review it for "appropriateness," but I was surprised and delighted to discover a plethora of Doctor Who books and other merchandising material geared toward young fans.

But, oh, yeah, I've got work to do.

Saturday, March 31, 2007

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

The hangover

I should've paced myself better. Since first tasting temptation in October, I dabbled — a bit here, a bit there, mostly according to availability. I showed some resolve even, around Christmas, so as it wouldn't interfere with various commitments.

But over the last couple weeks, I couldn't turn the pages fast enough.

Hangover Square, by Patrick Hamilton, has a decidedly more modern feel than any other of his work that I've read. Shorter sentences. Gone are the florid phrases, the Dickensian descriptions. (Hamilton stills pays homage though: our protagonist finds some healing power in the reading of David Copperfield.) The scenery is unimportant; it's what goes on inside his head that colours his world.

Hangover Square, by Patrick Hamilton, has a decidedly more modern feel than any other of his work that I've read. Shorter sentences. Gone are the florid phrases, the Dickensian descriptions. (Hamilton stills pays homage though: our protagonist finds some healing power in the reading of David Copperfield.) The scenery is unimportant; it's what goes on inside his head that colours his world.

While all Hamilton's stories are bleak with unsavory characters, this novel feels downright sinister. I see for the first time in his novels the creepy, Hitchcockian quality of a psychological thriller, such as seen in Rope and Gaslight (of which I'm familiar with only the popular film adaptations), on which Hamilton's reputation was made. (Actually Hamilton did not approve of the film treatment of his works. I mean here only to underscore the presence of a dark and criminal element not fully evident in the other Hamilton novels I've read.)

It's 1939. Something's not right. Europe is on the brink of war. George Harvey Bone is on the brink of war within himself, about to be fully invaded by his other, murderous self.

George Harvey Bone is a large man, aimless, but kindly, a bit of a sap. He's smitten with a relatively unsuccessful film actress — he's a hanger-on, and a purveyor of whiskey. Her gang — his "friends" — makes fun of his "dumb moods." The thing is, George Harvey Bone has episodes — the blackouts are getting longer, more frequent. Drink is in great part responsible, and Netta's in great part responsible for all the drink.

Some automaton takes over, operates on a simpler, baser level.

We are treated to a few of these episodes; in fact the novel opens with one, and within those first few pages we know this "other" George means to do away with Netta.

The episodes are punctuated with "clicks" and "snaps" and "cracks." Hamilton uses these verbs a great deal: they ease the reader between George's two worlds, but used "normally" with heels and tongues they also serve to create anticipation for the next episode.

George finally is quite sympathetic. He reestablishes contact with an old school friend. He's adopted the rooming house cat for his own. While most of the novel follows George's perspective, 2 short chapters give outside views: one from a young pub patron who observes Netta's group and meets George, one from George's landlady. I was rooting for George to get away from it all — a change of scene, a new crowd would do him so much good — read a little more Dickens, go see a doctor.

But part of me was rooting for the other George too, to do those nogoodniks in (Fascists they were!), they deserve it.

Aurgh! The suspense! Will he? won't he? do I really want him to? wait a minute, exactly how trustworthy is any of either of George's perspectives anyway? and what about the cat?

This book is unsettling in so many ways, not least its eerily credible view of mental illness as seen from the inside.

Considerable liberties were taken with the 1945 film version of Hangover Square, starring Laird Cregar.

An audio CD recording of Hangover Square is scheduled to be released in September 2007 and is available for preorder.

There's something delicious in discovering a "new" author with a whole catalogue of worlds to drown oneself in. There's something infinitely sad in having drunk them all with the knowledge that he can issue no new masterworks from beyond the grave. There's something tragic in knowing they keep the good stuff in a locked cupboard. Well, maybe not the good stuff, but an extra stash. For just in case. For a rainy day. And I don't think the cupboard's actually locked, just inaccessible, highly inconvenient. I mean: there's something tragic in knowing that there's more, somewhere, but it's out of print.

Very sadly, I have no more Patrick Hamilton on my shelf to read, nor is there much more available to read, barring serendipitous finds in used bookshops and/or extravagant expenditures. I'm crossing my fingers that next time my sister is in London she will manage to hunt down a copy of Impromptu in Moribundia. I plan to re-view both Rope and Gaslight in the not-too-distant future, this time with the eyes of a Hamilton expert (ahem). I plan to spill here everything I know about Patrick Hamilton, with a comprehensive index of everything I've posted on his works, a list of editions of his work, and links to other resources (including this fine report). Not that you care. But you should. He's really good.

But over the last couple weeks, I couldn't turn the pages fast enough.

Hangover Square, by Patrick Hamilton, has a decidedly more modern feel than any other of his work that I've read. Shorter sentences. Gone are the florid phrases, the Dickensian descriptions. (Hamilton stills pays homage though: our protagonist finds some healing power in the reading of David Copperfield.) The scenery is unimportant; it's what goes on inside his head that colours his world.

Hangover Square, by Patrick Hamilton, has a decidedly more modern feel than any other of his work that I've read. Shorter sentences. Gone are the florid phrases, the Dickensian descriptions. (Hamilton stills pays homage though: our protagonist finds some healing power in the reading of David Copperfield.) The scenery is unimportant; it's what goes on inside his head that colours his world.While all Hamilton's stories are bleak with unsavory characters, this novel feels downright sinister. I see for the first time in his novels the creepy, Hitchcockian quality of a psychological thriller, such as seen in Rope and Gaslight (of which I'm familiar with only the popular film adaptations), on which Hamilton's reputation was made. (Actually Hamilton did not approve of the film treatment of his works. I mean here only to underscore the presence of a dark and criminal element not fully evident in the other Hamilton novels I've read.)

It's 1939. Something's not right. Europe is on the brink of war. George Harvey Bone is on the brink of war within himself, about to be fully invaded by his other, murderous self.

George Harvey Bone is a large man, aimless, but kindly, a bit of a sap. He's smitten with a relatively unsuccessful film actress — he's a hanger-on, and a purveyor of whiskey. Her gang — his "friends" — makes fun of his "dumb moods." The thing is, George Harvey Bone has episodes — the blackouts are getting longer, more frequent. Drink is in great part responsible, and Netta's in great part responsible for all the drink.

Click! . . .

Here it was again! He was in London, in a taxi at night and it had happened again!

"Click..." That was the way to describe it. It was like the click of a camera shutter. Shutter! That was the word. A shutter had come down over his brain: he had shut down: he was shut out from the world he had been in a moment before.

The world he was in now was the same in shape, the same to look at, but "dead," silent, mysterious, as though its scenes and activities were all taking place in the tank of an aquarium or even at the bottom of the ocean — a noiseless, intense, gliding, fishy world.

It was as though he had suddenly gone deaf — mentally deaf.

It was as though one had blown one's nose too hard, and the outer world had become dim and dead. It was as though one gone into a sound-proof telephone booth and shut the door tightly on oneself.

There were a hundred and one ways of describing it. When it happened to him he always tried to describe it to himself — to analyse it — because it was such a funny feeling. He was not frightened by it, because he was used to it by now. But it was happening a good deal too often nowadays, and he wished it wouldn't.

It was such a weird feeling: it was always novel, and, in a way, interesting to him. It was though the people around him, although they moved about, were not really alive: as though their existence had no motive or meaning, as though they were shadows — rabbits or butterflies or kangaroos thrown on the wall by an amateur conjurer with a candle. And although they talked, and although he could understand what they said, it was not as though they had spoken in the ordinary way, and it was an effort to understand and to answer.

Take Netta, for instance, who was rather oddly and inexplicably sitting beside him in this taxi. He knew it was Netta well enough — but it was a different Netta. Although he could see her she was remote, almost impalpable, miles away — like a voice over the telephone, or the mental construction of the owner of a voice one might make while phoning — a ghost, if you liked.

He could hear and understand the words, but for the moment he couldn't gather what they meant. They seemed divorced from any context; or at any rate he didn't know what the context was. So he didn't answer. For the moment anyway, he was too interested in what had happened in his head.

Then, gradually, and as usual, and without his being aware of it, the feeling of novelty and strangeness, his conscious knowledge of the transition, of the falling of the shutter, faded away. And the world he was in now, the world under the sea, was his proper world, the only one he knew.

Some automaton takes over, operates on a simpler, baser level.

We are treated to a few of these episodes; in fact the novel opens with one, and within those first few pages we know this "other" George means to do away with Netta.

The episodes are punctuated with "clicks" and "snaps" and "cracks." Hamilton uses these verbs a great deal: they ease the reader between George's two worlds, but used "normally" with heels and tongues they also serve to create anticipation for the next episode.

George finally is quite sympathetic. He reestablishes contact with an old school friend. He's adopted the rooming house cat for his own. While most of the novel follows George's perspective, 2 short chapters give outside views: one from a young pub patron who observes Netta's group and meets George, one from George's landlady. I was rooting for George to get away from it all — a change of scene, a new crowd would do him so much good — read a little more Dickens, go see a doctor.

But part of me was rooting for the other George too, to do those nogoodniks in (Fascists they were!), they deserve it.

Aurgh! The suspense! Will he? won't he? do I really want him to? wait a minute, exactly how trustworthy is any of either of George's perspectives anyway? and what about the cat?

This book is unsettling in so many ways, not least its eerily credible view of mental illness as seen from the inside.

Considerable liberties were taken with the 1945 film version of Hangover Square, starring Laird Cregar.

An audio CD recording of Hangover Square is scheduled to be released in September 2007 and is available for preorder.

There's something delicious in discovering a "new" author with a whole catalogue of worlds to drown oneself in. There's something infinitely sad in having drunk them all with the knowledge that he can issue no new masterworks from beyond the grave. There's something tragic in knowing they keep the good stuff in a locked cupboard. Well, maybe not the good stuff, but an extra stash. For just in case. For a rainy day. And I don't think the cupboard's actually locked, just inaccessible, highly inconvenient. I mean: there's something tragic in knowing that there's more, somewhere, but it's out of print.

Very sadly, I have no more Patrick Hamilton on my shelf to read, nor is there much more available to read, barring serendipitous finds in used bookshops and/or extravagant expenditures. I'm crossing my fingers that next time my sister is in London she will manage to hunt down a copy of Impromptu in Moribundia. I plan to re-view both Rope and Gaslight in the not-too-distant future, this time with the eyes of a Hamilton expert (ahem). I plan to spill here everything I know about Patrick Hamilton, with a comprehensive index of everything I've posted on his works, a list of editions of his work, and links to other resources (including this fine report). Not that you care. But you should. He's really good.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Monday, March 26, 2007

Spring

Last week's rain wasn't strong enough to melt all the snow. The sun peaked out from time to time and the birds were singing, but Helena had already pinpointed the surest sign of spring in the streets:

"Mommy, mommy, where's my bicycle? Can you take out my bicycle? Can I ride my bicycle to the park, Mommy? I want to ride my bicycle. Where's my bicycle, Mommy?"

So I pulled the bicycle out of storage, and we went to the park with the bicycle.

Of course, our day (Saturday), was put to bed under a fresh, fluffy white coverlet. The park is one big mudpuddle and the hopscotch grids in the schoolyard still lie under an icy crust, but Helena knows where her bicycle is and for the time-being that's all that matters.

"Mommy, mommy, where's my bicycle? Can you take out my bicycle? Can I ride my bicycle to the park, Mommy? I want to ride my bicycle. Where's my bicycle, Mommy?"

So I pulled the bicycle out of storage, and we went to the park with the bicycle.

Of course, our day (Saturday), was put to bed under a fresh, fluffy white coverlet. The park is one big mudpuddle and the hopscotch grids in the schoolyard still lie under an icy crust, but Helena knows where her bicycle is and for the time-being that's all that matters.

Thursday, March 22, 2007

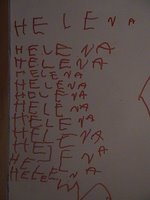

Name and number

Tuesday Helena came home from daycare and wrote her name on her whiteboard. Repeatedly. It's what she's been doing with her every spare minute since. Her letters are well-formed (mostly) and in the right order.

Tuesday Helena came home from daycare and wrote her name on her whiteboard. Repeatedly. It's what she's been doing with her every spare minute since. Her letters are well-formed (mostly) and in the right order.A few days beforehand, she spontaneously recited her phone number. Correctly, without hesitation.

At age 4 and almost a half, I don't find these developments particularly noteworthy in themselves.

What I find remarkable in them is that they confirm my suspicions regarding her perfectionist personality: something's not worth doing (publicly, at any rate) until you can do it right. (I hope I haven't reinforced this behaviour. I've been known to exercise this tendency myself, and I well know that it's not a very effective way to learn to do anything.)

I've seen it in her approach to new vocabulary, new songs and games, new playground equipment. I rarely see in her the gradual acquisition of a concept or skill; I see lightbulb moments.

For months I've seen Helena's classmates struggle with writing their names, putting "R"s and "E"s backwards, missing a letter here or there, those with 3- and 4-letter names getting them pretty close. All this time, Helena would write simply "H," and leave it at that, seemingly uninterested in pursuing the prospect of writing anything any further.

Similarly, she hasn't shown interest in her phone number. I've occasionally asked her to repeat after me as I divide it into 3- and 4-digit blocks, but she wanders off instead to count things meaningfully, using numbers in their proper order.

But Helena's been paying attention all this time after all. Studying. Maybe practicing in her head or under her breath. But no faltering under eyewitness.

If it's worth doing, it's worth doing right. I'll be leaving my tax forms out for her perusal.

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Twenty thousand reasons

But I need give you only one: it's painfully beautiful.

Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton, contains 3 volumes — The Midnight Bell (Bob's story), The Siege of Pleasure (Jenny's story), and The Plains of Cement (Ella's Story). They were originally published separately (in 1929, 1932, and 1934) before being collected (in 1935), and each is self-contained.

The Midnight Bell is a pub where Bob is waiter and Ella is barmaid. (Much of the first volume is autobiographical:) Bob falls in love — rather, develops an obsession — with Jenny, a prostitute (the middle book tells how Jenny came to live the life she lives). Ella, meanwhile, is courted by a regular.

The pub is peopled by authentic "characters" — take Mr Sounder, whose first beer is in the nature of an investment as he relies on other patrons to pay his expenses.

These people's lives are replete with authentic non-events — the difficulties of umbrella-sharing, for example.

I've quoted from each of the volumes as I made my way through them (1, 2, 3, 4). I don't know what Hamilton's appeal is to me. There's a directness about very complicated thought processes. His dialogue is simple, neatly captured. But he can be verbose too. It's all very dark, but there's a clever wit. A tragic trueness. It's best, I guess, to let those excerpts speak for themselves.

Dan Rhodes in the Guardian says, "It's bleak and brilliant, and an authentic lost classic."

Ella's story is my favourite. She's the sensible one; she knows her weaknesses, but even she can't help but give in to them (making her most tragic of all, perhaps). Ella is ordinary, and her story, like that of most ordinary people everywhere, involves a lot of nothing in particular.

This summation occurs in the final pages, and after all that had transpired it brought tears to my eyes. On top of everything, Ella's story has the very saddest closing sentence I've ever read.

Twenty Thousand Streets is published as a Vintage Classic. (A reading guide is available, but the first discussion point is a bit wrong-headed. The 3 volumes are not the same story from different points of view; they are the stories of 3 different characters that intersect and intertwine in the months up to Christmas. In fact, the bulk of Jenny's story, which starts just after Christmas, is a flashback to events taking place at least a year beforehand.)

The Random House UK website has a great deal of supplemental information, including Hamilton's own thoughts on this book in particular and on writing in general.

I urge you to pick up a copy of Twenty Thousand Streets before it's again allowed to fall out of print. Help ensure that doesn't happen.

Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton, contains 3 volumes — The Midnight Bell (Bob's story), The Siege of Pleasure (Jenny's story), and The Plains of Cement (Ella's Story). They were originally published separately (in 1929, 1932, and 1934) before being collected (in 1935), and each is self-contained.

The Midnight Bell is a pub where Bob is waiter and Ella is barmaid. (Much of the first volume is autobiographical:) Bob falls in love — rather, develops an obsession — with Jenny, a prostitute (the middle book tells how Jenny came to live the life she lives). Ella, meanwhile, is courted by a regular.

The pub is peopled by authentic "characters" — take Mr Sounder, whose first beer is in the nature of an investment as he relies on other patrons to pay his expenses.

These people's lives are replete with authentic non-events — the difficulties of umbrella-sharing, for example.

I've quoted from each of the volumes as I made my way through them (1, 2, 3, 4). I don't know what Hamilton's appeal is to me. There's a directness about very complicated thought processes. His dialogue is simple, neatly captured. But he can be verbose too. It's all very dark, but there's a clever wit. A tragic trueness. It's best, I guess, to let those excerpts speak for themselves.

Dan Rhodes in the Guardian says, "It's bleak and brilliant, and an authentic lost classic."

Ella's story is my favourite. She's the sensible one; she knows her weaknesses, but even she can't help but give in to them (making her most tragic of all, perhaps). Ella is ordinary, and her story, like that of most ordinary people everywhere, involves a lot of nothing in particular.

And, indeed, what had taken place in those dull months? Nothing, really, whatever — nothing out of the common lot of any girl in London, if you came to think about it. She had had an elderly admirer, (what girl has not been in such a dilemma at some time or another?) about whom she had not been able fully to make up her mind. Nothing in that. A connection of hers had been ill — a stepfather whom she disliked, and there had been domestic troubles. Nothing in that. She had been depressed by the fogs and the cold — who had not? She had looked for another job, but it hadn't come to anything — an ordinary enough occurrence. She had had what the gentlemen in the bar would have called a slight 'crush' on the waiter. But that was not the first time a girl had 'crush' on a man she worked with. You soon get over that. No — seen from an outsider's point of view she was lucky if she had nothing more to grumble about, and the gentlemen committed no error in tact in joking with her and teasing her just as usual.

This summation occurs in the final pages, and after all that had transpired it brought tears to my eyes. On top of everything, Ella's story has the very saddest closing sentence I've ever read.

Twenty Thousand Streets is published as a Vintage Classic. (A reading guide is available, but the first discussion point is a bit wrong-headed. The 3 volumes are not the same story from different points of view; they are the stories of 3 different characters that intersect and intertwine in the months up to Christmas. In fact, the bulk of Jenny's story, which starts just after Christmas, is a flashback to events taking place at least a year beforehand.)

The Random House UK website has a great deal of supplemental information, including Hamilton's own thoughts on this book in particular and on writing in general.

My present book is I think, streets ahead of what I've done before. . . there is only one theme of the HardycumConrad great novel — that is, that this is a bloody awful life, that we are none of us responsible for our own lives and actions, but merely in the hands of the gods, that Nature don't care a damn, but looks rather picturesque in not doing so, and that whether you're making love, being hanged or getting drunk, it's all a futile way of passing the time in the brief period allotted to us preceding death. It is the poet's business to put into words the universal wail of humanity at not being able to get everything it wants exactly when it wants it.

I urge you to pick up a copy of Twenty Thousand Streets before it's again allowed to fall out of print. Help ensure that doesn't happen.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

The big joke

Nobody told me.

Nobody told me the road to the cottage was impassable, that we'd have to park a ways off, transfer our baggage to the sled, that we'd have to skidoo the rest of the way, over a lake. ("Just like the eskimos, in the old days.") I'd've dressed differently, dressed the girl warmer; in an instant, or rather in the 30-odd-minute skidoo ride across a lake not sheltered from wind, I've undone all the recent days of keeping the girl home to get her fully healthy, to finally get rid of that pesky cold once and for all. I'd've packed differently, more compactly; I'd've spent a few more minutes to dig out a larger dufflebag instead of stuffing Helena's jigsaw puzzle and her board game into a plastic shopping bag at the last minute. Nobody told me about crossing the lake, about the consoling physics of the thing, that, though the sight of puddles unnerved me, though they were evidence of last week's rain and a bit of surface melt, they topped at least 4 feet of ice. But perhaps it's for the best that nobody told me about some of these things. (Please, nobody tell my mother.)

Really, I would've packed differently. I wouldn't've brought my hardcover copy of Infinite Jest, for example. I'd planned that as my reading material for some time already; how perfect it was for a weekend in a shack in the woods in the middle of nowhere, and I'd joked:

1. I wouldn't run out of reading material.

2. I'd be forced to just read it already, having no alternate reading material.

3. I could use the pages for extra insulation between layers of clothing.

4. Page after read page could feed the fire in times of necessity.

5. I'd like to hurl it across a room. In times of cabin fever, it would be a sure conversation starter, or stopper, as appropriate.

6. If one kind of cabin fever led to another, it would serve as a perfect murder weapon.

As we skidooed across the puddled, if allegedly thoroughly frozen, lake, I considered climbing over into the sled, retrieving it from its last-minute what-do-you-mean-we-park-the-vehicle-here plastic bag and throwing it overboard to lighten our load.

Nobody told me that we'd all be sharing one cottage, instead of spreading out over two, as is our usual summer habit. It makes sense, of course. One of them was fairly locked up for the winter; only one cottage to run, one generator (just like the eskimos use), one wood stove to tend. Closer, warmer quarters. But nobody told me. No television, no radio, even no internet — these I can do without. But no separate corners to retreat to. No stack of old National Geographics to turn to in desperation as entertainment fodder for the child. And no privacy for lovers.

My idea of winter activities involves bottles of wine, books, blankets. On occasion I look forward to conversation. And jigsaw puzzles. Jigsaw puzzles have something festive about them, an indoor activity that engages a team spirit when conversation fails to enthrall.

I'd imagined gentle walks this weekend, dragging Helena about on her sled, building a snow fort. Not all that different from our time in the city, actually.

But here we drove hours north in a gas-guzzling vehicle, to be with nature, like the eskimos, enjoying the roar of the generator, the stench of skidoo fuel, our god-given right to figuratively piss in the woods; to be put off by the fact that it's snowing and too cold to spend much time outside, other than a quick, indulgent skidoo zip down the trail and back again; to stay in, and try to get warm, then keep warm.

I'm struck (as were the characters in The Goldbug Variations) just how much energy is devoted to bare maintenance. Meal preparation and clean-up stretch on forever. There's not even much time for reading.

To be honest, Infinite Jest is not all the reading material I had on hand. As departure time neared, I was within a few dozen pages of the end of Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, and nothing — but nothing! — could've persuaded me to abandon it and forget it for even a mere 3 days. Of course I brought it with me, and finished it and cried. J-F brought my review copy of Louis Theroux's The Call of the Weird, which he was already well into (and which he may review for me).

So at the end of that first day, I'm left with that big joke of a book, Infinite Jest.

I've had a copy for about a year now, and I've been meaning to read it, see what all the fuss is about, for longer still. I'm on page 74; that is, I've barely opened it.

Part of me wants to hate this book, I'm not sure why. Part of me is succeeding. Some bits are kind of funny, some bits are kind of clever. I especially liked the scene where he's sitting around waiting for this woman to come with his drugs. I like the idea of the footnotes, but they seem to be put to inconsistent use, sometimes being more scientific or academic and other times used to editorialize; the blend doesn't sit comfortably with me. I'm a bit put off by the references to Quebec politics; having relatively recently become a resident I feel like I'm being put on the defensive (though at this point I know neither how it will figure in the plot nor what commentary if any is being made on Quebec society), but I'm intrigued that this part of the world and its history should figure at all in an American novel. I'm especially peeved by the narrator's "like" tic ("there were like a dozen..."), which thus far doesn't seem to contribute much by way of tone or voice or whatever literary attribute you'd like to call it.

Mostly, it bores me.

Maybe I'm not ready for it after all. But if not now, when? I feel committed now; I've started, I'll finish. (I should say I'm a David Foster Wallace virgin, apart from, I now realize, his article on English usage in Harper's, which I'd read when it came out, loved, and saved.) I'm loathe to put it off any longer, but it's not gripping me.

Maybe I'll never get the big joke. Maybe that's the joke.

Nobody told me the road to the cottage was impassable, that we'd have to park a ways off, transfer our baggage to the sled, that we'd have to skidoo the rest of the way, over a lake. ("Just like the eskimos, in the old days.") I'd've dressed differently, dressed the girl warmer; in an instant, or rather in the 30-odd-minute skidoo ride across a lake not sheltered from wind, I've undone all the recent days of keeping the girl home to get her fully healthy, to finally get rid of that pesky cold once and for all. I'd've packed differently, more compactly; I'd've spent a few more minutes to dig out a larger dufflebag instead of stuffing Helena's jigsaw puzzle and her board game into a plastic shopping bag at the last minute. Nobody told me about crossing the lake, about the consoling physics of the thing, that, though the sight of puddles unnerved me, though they were evidence of last week's rain and a bit of surface melt, they topped at least 4 feet of ice. But perhaps it's for the best that nobody told me about some of these things. (Please, nobody tell my mother.)

Really, I would've packed differently. I wouldn't've brought my hardcover copy of Infinite Jest, for example. I'd planned that as my reading material for some time already; how perfect it was for a weekend in a shack in the woods in the middle of nowhere, and I'd joked:

1. I wouldn't run out of reading material.

2. I'd be forced to just read it already, having no alternate reading material.

3. I could use the pages for extra insulation between layers of clothing.

4. Page after read page could feed the fire in times of necessity.

5. I'd like to hurl it across a room. In times of cabin fever, it would be a sure conversation starter, or stopper, as appropriate.

6. If one kind of cabin fever led to another, it would serve as a perfect murder weapon.

As we skidooed across the puddled, if allegedly thoroughly frozen, lake, I considered climbing over into the sled, retrieving it from its last-minute what-do-you-mean-we-park-the-vehicle-here plastic bag and throwing it overboard to lighten our load.

Nobody told me that we'd all be sharing one cottage, instead of spreading out over two, as is our usual summer habit. It makes sense, of course. One of them was fairly locked up for the winter; only one cottage to run, one generator (just like the eskimos use), one wood stove to tend. Closer, warmer quarters. But nobody told me. No television, no radio, even no internet — these I can do without. But no separate corners to retreat to. No stack of old National Geographics to turn to in desperation as entertainment fodder for the child. And no privacy for lovers.

My idea of winter activities involves bottles of wine, books, blankets. On occasion I look forward to conversation. And jigsaw puzzles. Jigsaw puzzles have something festive about them, an indoor activity that engages a team spirit when conversation fails to enthrall.

I'd imagined gentle walks this weekend, dragging Helena about on her sled, building a snow fort. Not all that different from our time in the city, actually.

But here we drove hours north in a gas-guzzling vehicle, to be with nature, like the eskimos, enjoying the roar of the generator, the stench of skidoo fuel, our god-given right to figuratively piss in the woods; to be put off by the fact that it's snowing and too cold to spend much time outside, other than a quick, indulgent skidoo zip down the trail and back again; to stay in, and try to get warm, then keep warm.

I'm struck (as were the characters in The Goldbug Variations) just how much energy is devoted to bare maintenance. Meal preparation and clean-up stretch on forever. There's not even much time for reading.

To be honest, Infinite Jest is not all the reading material I had on hand. As departure time neared, I was within a few dozen pages of the end of Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, and nothing — but nothing! — could've persuaded me to abandon it and forget it for even a mere 3 days. Of course I brought it with me, and finished it and cried. J-F brought my review copy of Louis Theroux's The Call of the Weird, which he was already well into (and which he may review for me).

So at the end of that first day, I'm left with that big joke of a book, Infinite Jest.

I've had a copy for about a year now, and I've been meaning to read it, see what all the fuss is about, for longer still. I'm on page 74; that is, I've barely opened it.

Part of me wants to hate this book, I'm not sure why. Part of me is succeeding. Some bits are kind of funny, some bits are kind of clever. I especially liked the scene where he's sitting around waiting for this woman to come with his drugs. I like the idea of the footnotes, but they seem to be put to inconsistent use, sometimes being more scientific or academic and other times used to editorialize; the blend doesn't sit comfortably with me. I'm a bit put off by the references to Quebec politics; having relatively recently become a resident I feel like I'm being put on the defensive (though at this point I know neither how it will figure in the plot nor what commentary if any is being made on Quebec society), but I'm intrigued that this part of the world and its history should figure at all in an American novel. I'm especially peeved by the narrator's "like" tic ("there were like a dozen..."), which thus far doesn't seem to contribute much by way of tone or voice or whatever literary attribute you'd like to call it.

Mostly, it bores me.

Maybe I'm not ready for it after all. But if not now, when? I feel committed now; I've started, I'll finish. (I should say I'm a David Foster Wallace virgin, apart from, I now realize, his article on English usage in Harper's, which I'd read when it came out, loved, and saved.) I'm loathe to put it off any longer, but it's not gripping me.

Maybe I'll never get the big joke. Maybe that's the joke.

Monday, March 19, 2007

The wonders of love

Poor Ella!

— from The Plains of Cement, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

'It's wonderful, isn't it,' said Mr Eccles. 'Just to be strolling arm-in-arm like this.'

They were walking briskly now by the lake in the direction of Clarence Gate, whence they were to emerge for their supper into London, whose lights were now seen glittering, and whose buses and trains could be heard roaring, an entirely furious and disparaging welcome to the surface to divers in its dark parks.

So soon as they had started walking Mr Eccles had become a different creature — experiencing an influx of all that cheerful sense of manhood and resilience known to overtake gentlemen who have just been kissing young ladies a great deal and for the first time, and holding her arm and becoming loquacious. Ella, having got cold sitting out all that time, was also glad to be moving, and inclined for this reason to reflect his mood in some measure, however doubtful her inner frame of mind.

'Yes — it is,' she said, not finding it in her heart to damp his spirits, but her heart sank. It sank firstly because his remark, together with some which had preceded it, were all manifesting a growing air of jubilant proprietorship which, in spite of her late tacit agreement, frightened her more and more every moment; and secondly because, if she did sincerely consent, and if walking thus with him was 'wonderful,' as he had assured her it was, then she must have a blind spot about wonder in general, and would never know the wonders of love. For all she felt was a feeling of being no more and no less puzzled and ordinary than she was at any other moment of the day.

'It changes everything, doesn't it,' said Mr Eccles. 'Love.'

— from The Plains of Cement, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Friday, March 16, 2007

Woman's work

We know how Jenny ends up: a prostitute. The tension in her story — her backstory — The Siege of Pleasure, the second volume in the threesome that makes up Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, is in watching her fall and not being able to stop her.

— from The Siege of Pleasure, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

It mattered not to Jenny, who had weighty work on hand — that is not to say weighty in the figurative sense of the term — but work which involved hauling out mighty bedsteads so as to get round and make the bed, dragging out monstrous furniture so as to dust behind it, emptying vast Edwardian basins of their brimming soap-grey lakes, lifting enormous and replenished jugs and lowering them at arm's length slowly lest they smashed the massive crockery, transporting wabbling pails, as heavy as children but not so tractable, down stairs and along passages, and carrying piled trays about in a world wherein practically everything was breakable, and only terrific muscular exertion and an agonized striving after balance could avert the impending crash — in brief, 'woman's work.'

— from The Siege of Pleasure, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Thursday, March 15, 2007

"The susceptibility of mankind to poetic precedents"

There are few motives so dangerous as theatricality and no wildness is so futile as deliberate wildness. Bob conceived it his duty to get wildly drunk and do mad things. He had no authentic craving to do so: he merely objectivized himself as an abused and terrible character, and surrendered to the explicit demands of drama. The motivation of popular fiction in behaviour — the susceptibility of mankind to poetic precedents — are subjects which will one day be treated with the gravity they deserve. In deciding to get wildly drunk and do mad things, Bob believed he was achieving something of vague magnificence and import, redeeming and magnifying himself — cutting a figure before himself and the world. The fact that, in deliberately attempting to get wildly drunk and do mad things, he might actually get wildly drunk, and actually do mad things, completely eluded him.

— from The Midnight Bell, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

Drunk with Patrick Hamilton

Men! They thrust their hats back on their heads; they put their feet firmly on the rail; they looked you straight in the eye; they beat their palms with their fists, and they swilled largely and cried for more. Their arguments were top-heavy with the swagger of altruism. They appealed passionately to the laws of logic and honesty. Life, just for to-night, was miraculously clarified into simple and dramatic issues. It was the last five minutes of the evening, and they were drunk.

And they were in every phase of drunkenness conceivable. They were talking drunk, and confidential drunk, and laughing drunk, and beautifully drunk, and leering drunk, and secretive drunk, and dignified drunk, and admittedly drunk, and fighting drunk, and even rolling drunk. One gentleman, Bob observed, was patently blind drunk. Only one stage off dead drunk, that is — in which event he would not be able to leave the place unassisted.

And over all this ranting scene Ella, bright and pert and neat and industrious, held her barmaid's sway.

— from The Midnight Bell, in Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, by Patrick Hamilton.

Labels:

Patrick Hamilton

Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Dalek-building in times of plague

(In which Helena discovers the wondrous glory that is duct tape.)

We'd been suffering a kind of cabin fever that spilled all over our weekend, the 3 of us variously having our sinuses infected (me), throats strepped (Helena, suspected — with possible symptoms, and a memo from the daycare that scarlet fever is making its rounds — but in the end not; but home for a few days all the same), and lungs phlegmed (J-F), although it was better than the more literal cabin fever we'd been anticipating having to endure (in a shack in the woods in the snow with in-laws).

I'd been looking forward to starting book #3 of my Chunkster Challenge — Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace — and a shack in the woods in the snow with in-laws for the weekend seemed just the right time and place for it. The change in weekend plans heralded a change in reading material; the tingling behind my eyes and general heaviness of head put me in no mood for jesting but was rather more suited to an appropriately pseudoephedrine-enhanced reading of The Exquisite, by Laird Hunt, which, I neglected to say, reminded me of both The Street of Crocodiles (Bruno Schulz) and The Dodecahedron (Paul Glennon), in ways I care not to elaborate (because, really, I'm still not thinking all that clearly) beyond noting the problem (for the reader, as well as for the characters) common to all of trying to decipher objective reality from how the subjective mind creates its own narrative of it.

Also, I'm diving back into Patrick Hamilton (Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky), my way of celebrating his upcoming birthday. It's not right that he should sit there so long unread, and it's not right that I should deny myself the pleasure. It's a very different reading experience from, say, The Gold Bug Variations, which I readily proclaim to love (it's as if I've never really loved a book before). Hamilton makes me turn pages, I crave it, every knowing glance and every second guess, even though I know it's going to end badly; Hamilton is a drug.

Helena, still with a low fever, after a single day of feeling tired and resting was no longer acting sick at all. I ran out of energy long before she ran out of suggestions for games I should play with her. Even when she's engaged in solitary activities, she prefers that I'm by her side, colouring my own sheet of paper or drawing my own letters (and not with my nose in a book and a coffee at hand, although some days she's more accepting of this tendency of mine than others). I was tired of the options Helena offered me.

"Why don't you build a Dalek?" I flippantly suggested (having recently read about a contest).

And away she went.

I am proud to say that this Dalek is entirely of her own invention. I offered Helena an array of materials to choose from. I stepped in when she neared tears over trouble affixing its... hmm... appendage, and brought some duct tape to the rescue (ah, duct tape!), after which I stood by and cut pieces according to her specifications. Helena saw fit to dress the Dalek in duct tape almost entirely; she really likes the colour, and it's shiny besides.

(The Dalek Song.)

A second Dalek is in the works, but Helena's interest has waned, which is just as well. There's already a Dalek among the elephants; the last thing I want is a whole army of Daleks in the house when our defenses are down.

We'd been suffering a kind of cabin fever that spilled all over our weekend, the 3 of us variously having our sinuses infected (me), throats strepped (Helena, suspected — with possible symptoms, and a memo from the daycare that scarlet fever is making its rounds — but in the end not; but home for a few days all the same), and lungs phlegmed (J-F), although it was better than the more literal cabin fever we'd been anticipating having to endure (in a shack in the woods in the snow with in-laws).

I'd been looking forward to starting book #3 of my Chunkster Challenge — Infinite Jest, by David Foster Wallace — and a shack in the woods in the snow with in-laws for the weekend seemed just the right time and place for it. The change in weekend plans heralded a change in reading material; the tingling behind my eyes and general heaviness of head put me in no mood for jesting but was rather more suited to an appropriately pseudoephedrine-enhanced reading of The Exquisite, by Laird Hunt, which, I neglected to say, reminded me of both The Street of Crocodiles (Bruno Schulz) and The Dodecahedron (Paul Glennon), in ways I care not to elaborate (because, really, I'm still not thinking all that clearly) beyond noting the problem (for the reader, as well as for the characters) common to all of trying to decipher objective reality from how the subjective mind creates its own narrative of it.

Also, I'm diving back into Patrick Hamilton (Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky), my way of celebrating his upcoming birthday. It's not right that he should sit there so long unread, and it's not right that I should deny myself the pleasure. It's a very different reading experience from, say, The Gold Bug Variations, which I readily proclaim to love (it's as if I've never really loved a book before). Hamilton makes me turn pages, I crave it, every knowing glance and every second guess, even though I know it's going to end badly; Hamilton is a drug.

Helena, still with a low fever, after a single day of feeling tired and resting was no longer acting sick at all. I ran out of energy long before she ran out of suggestions for games I should play with her. Even when she's engaged in solitary activities, she prefers that I'm by her side, colouring my own sheet of paper or drawing my own letters (and not with my nose in a book and a coffee at hand, although some days she's more accepting of this tendency of mine than others). I was tired of the options Helena offered me.

"Why don't you build a Dalek?" I flippantly suggested (having recently read about a contest).

And away she went.

I am proud to say that this Dalek is entirely of her own invention. I offered Helena an array of materials to choose from. I stepped in when she neared tears over trouble affixing its... hmm... appendage, and brought some duct tape to the rescue (ah, duct tape!), after which I stood by and cut pieces according to her specifications. Helena saw fit to dress the Dalek in duct tape almost entirely; she really likes the colour, and it's shiny besides.

(The Dalek Song.)

A second Dalek is in the works, but Helena's interest has waned, which is just as well. There's already a Dalek among the elephants; the last thing I want is a whole army of Daleks in the house when our defenses are down.

Thinking

Thanks to both Mental Multivitamin and So Many Books for nominating me for a thinking blogger award.

Thanks to both Mental Multivitamin and So Many Books for nominating me for a thinking blogger award.While it is a very simple meme, it says quite a lot more than meets the eye. What makes people think?

I've already spent far too much time trying to trace the meme in both directions, backward from me and forward from its source. While it is currently traveling in book blog circles, it seems to have originated among science-oriented blogs — I haven’t yet been able to make those 2 meme ends meet (and would love to see them come full circle).

(The instructions ask me to list 5 blogs that make me think; it's a near impossible task to choose from among the dozens I visit regularly, all of which spark my brain in different ways. I'd like to pay it forward as best as I can and, I hope, introduce readers to places they may be less familiar with; but in the interest of keeping my list meaningful, as well as preventing duplication of those nominated elsewhere, I limit myself to 3.)

Here are my thinking blogger award nominations (listed alphabetically), for blogs that stretch me to think, albeit in vastly different directions:

Collision Detection

Counterbalance

Speed of Life

Sunday, March 11, 2007

The horror and the herring

This weekend I finished reading The Exquisite, by Laird Hunt. Trippy. That's pretty much all I can say. Trippy.

Here's a little (not-particularly-trippy) taste:

The whole book feels like a David Lynch movie (but only Dune, with its spice-blue eyes, is referenced explicitly). I like the vagueness of the reference to the horrors downtown (9/11), how it helps impart a sense of (and a sense behind) the danse macabre nihilistic decadence that takes hold of this odd assemblage of characters.

The review that made me pick up The Exquisite, followed by an interview.

Here's a little (not-particularly-trippy) taste:

Mr Kindt loved a good cigar, and he would always, with impeccable courtesy, offer me one. Dutch Masters was the brand he preferred, and he didn't mind if I chuckled about it like it was a joke. In fact, as we have seen, not only did he like for me to laugh about things, he insisted I do so. You have such a very pleasant laugh, it's so rich and hearty, I find it invigorating, he would say. He was just about as quick with a compliment as he was with a cigar. Apparently I had nice manners and nice features and "fine, strong shoulders" and a nice way of holding a plastic-tipped Premium. Generally, if I was smoking alone, I smoked Merits, but in Mr Kindt's company it was cigars. Mr Kindt thought very little indeed of cigarettes, "those miniature albino cigar," "those blatant disease-carrying delivery systems for brand names." There was no reason whatsoever, he said, to suck smoke all the way down into the lungs, which was the custom with cigarettes. The mouth, which held the tongue and the mechanisms of taste, was the appropriate receptacle. Its highly permeable membranes eagerly invited tobacco's active compounds to enter the "inward-leading complex" of blood vessels they played hos to. And of course, he added, cigars tasted much better. I wasn't at all sure about this last point, especially when it came to Dutch Masters, but I didn't argue. I didn't argue either when Mr Kindt would talk, with a funny little smile on his lips, about how pleasant it would be to die, if one had to, by having one's throat annihilated by cancer, or lungs filled with fragrant tar. When one is in the early, enthusiastic throes of a friendship, one lets a great deal slide.

The whole book feels like a David Lynch movie (but only Dune, with its spice-blue eyes, is referenced explicitly). I like the vagueness of the reference to the horrors downtown (9/11), how it helps impart a sense of (and a sense behind) the danse macabre nihilistic decadence that takes hold of this odd assemblage of characters.

The review that made me pick up The Exquisite, followed by an interview.

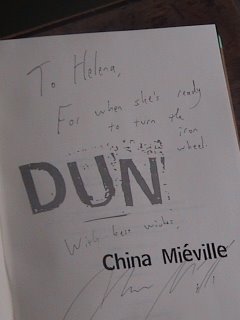

From China with best wishes

A dedication for Helena, from China Miéville, whose handwriting is eerily like my brother's. Come to think of it, their minds are rather similarly monstered too. I document the inscription here with these background thoughts as evidence to my future self that the cryptic-sounding message is authentic and not my brother's idea of a prank.

A dedication for Helena, from China Miéville, whose handwriting is eerily like my brother's. Come to think of it, their minds are rather similarly monstered too. I document the inscription here with these background thoughts as evidence to my future self that the cryptic-sounding message is authentic and not my brother's idea of a prank.More on Un Lun Dun:

My original verdict (so-so; full of unrealized potential) of the book, and my sister's verdict of a reading from the book.

Favourable review.

Interview, lengthy (scroll to bottom), but giving me a fresh appreciation for what Miéville is trying to do with this book.

Wednesday, March 07, 2007

"What could be simpler?"

"Nothing deserved wonder so much as our capacity to feel it."

I've been bowled over.

The book:

The Gold Bug Variations, by Richard Powers.

The plot:

Summary.

Of further interest:

Richard Powers as part of a panel discussion on the cultural gap between literature and science.

My initial impressions:

Resonance.

The impact:

I am in awe not only of this book and the ideas expressed therein, but of the effect of it's had on me. I love books, I do, but I'm always skeptical of people who readily proclaim favourites, or top 10s — so many books, and so many good ones, how can one choose? Today's favourites, for many, are often forgotten tomorrow. I understand the relative, and embrace it, but only insofar as it's an indicator of the definite. I want certainty. If I say "favourite," I mean forever; I won't say anything if I think I might be wrong.

I roll my eyes at people saying they did not want a book to end. But suddenly, for the first time, I know this feeling; I deliberately dragged out the reading of the Variations because I did not want it to end. I roll my eyes at people saying they hesitate to read more of an author because they fear it cannot live up to the precedent of a beloved book. But suddenly, for the first time, I know this feeling too; for all its accolades, I cannot imagine The Echo Maker affecting me so profoundly.

(This was book 2 of my (6 600+-page books in 6 months) Chunkster Challenge.)

A note on the style:

I found the cadence of the wording odd at first. The omission of articles, definite and indefinite. Which reminds me of science writing. So often those articles are redundant — they're understood and obvious. Doing away with them has the weird effect of being both more concise and precise and more ambiguous at the same time.

An example and point:

"For a brief moment, he achieved a synthesis between scientist's certainty in underlying particulars and the cleric's awe at the unmappable whole."

Also:

Curiously, Glenn Gould is never named by name, but there's no question as to the identity of the pianist whose recording of The Goldberg Variations permeates this book. Curious because there's a big deal made of naming things, classification — the arbitrariness of it, but the rightness of it, the impossibility of it, but the necessity of it. Where all meaning begins.

"A flat-out fascination with the threat, soberly maintaining that the only thing to do when the world begins to end is to stand aside and paint it. Uncover it. Name it."

There's something — something I can't quite articulate — being said about art here — painting (which figures in the book), literature (by extrapolation), but especially music. It's beyond science, beyond knowing, yet it's key to one's ability to know anything else. Indeed, art and love, those inarticulate things, the only things to really mean anything.

The trick to it:

Zooming in close on the trees, scratching the bark under a microscope, drilling deep inside; and zooming out quick for the forest, a macroscopic blur of colour and movement from far overhead. Seeing both views at the same time. It's something I think I do well in work and in life.

Some lessons:

"There are really only two careers that might be of any help. One can either be a surgeon or a musician." Which merits a discussion that leaves me tongue-tied.

"...he is struck by how much repetitive maintenance it takes just to exist. Existence is the cycle extraordinaire; everything tangent, constantly spinning just to stay in place." The everyday we try so hard to rise above is our purpose in life, the whole fucking point.

"One cannot step into the same theme twice."

A puzzle:

In sitting down to write this I thumbed through my copy for asterisked passages. Right at the front is something I meant to come back to.

I assumed it was a coded epigraph, but it seems it's a dedication, "which, according to Powers, remains unsolved but can be broken using a codex found in the final third of the book." Perhaps I'll crack it before I die. Perhaps it's meant for me.

The effect in toto:

I'll spend weeks to come listening to Bach like I've never listened to him before, and slipping in and out of infinite regress, resampling Godel, Escher, Bach. I will read Poe's The Gold Bug.

The Gold Bug Variations moves me the way Wings of Desire moves me (a favourite film). (I don't mean to draw nonexistent parallels here; the only obvious similarities are in their effect on me.)

(Hmm. Todd as an angel? A muse and a catalyst, outside of time. Who finally falls to earth.)

Variations on a theme, my theme.

There's a thematic resonance: a contemplation of the human experience. How characters refer to each other: in Variations, "Friend"; in Wings, "Compañero." How we assign meaning to meaninglessness. How I hear these works speaking to each other. How we are pure potential.

The sense of interconnectedness. The awe.

For years, for ever, I was skeptical, but I'm coming round: maybe, in the end, just maybe, love really does conquer all. (What could be simpler?)

Nous sommes embarqués...

I've been bowled over.

The book:

The Gold Bug Variations, by Richard Powers.

The plot:

Summary.

Of further interest:

Richard Powers as part of a panel discussion on the cultural gap between literature and science.

My initial impressions:

Resonance.

The impact:

I am in awe not only of this book and the ideas expressed therein, but of the effect of it's had on me. I love books, I do, but I'm always skeptical of people who readily proclaim favourites, or top 10s — so many books, and so many good ones, how can one choose? Today's favourites, for many, are often forgotten tomorrow. I understand the relative, and embrace it, but only insofar as it's an indicator of the definite. I want certainty. If I say "favourite," I mean forever; I won't say anything if I think I might be wrong.

I roll my eyes at people saying they did not want a book to end. But suddenly, for the first time, I know this feeling; I deliberately dragged out the reading of the Variations because I did not want it to end. I roll my eyes at people saying they hesitate to read more of an author because they fear it cannot live up to the precedent of a beloved book. But suddenly, for the first time, I know this feeling too; for all its accolades, I cannot imagine The Echo Maker affecting me so profoundly.

(This was book 2 of my (6 600+-page books in 6 months) Chunkster Challenge.)

A note on the style:

I found the cadence of the wording odd at first. The omission of articles, definite and indefinite. Which reminds me of science writing. So often those articles are redundant — they're understood and obvious. Doing away with them has the weird effect of being both more concise and precise and more ambiguous at the same time.

An example and point:

"For a brief moment, he achieved a synthesis between scientist's certainty in underlying particulars and the cleric's awe at the unmappable whole."

Also:

Curiously, Glenn Gould is never named by name, but there's no question as to the identity of the pianist whose recording of The Goldberg Variations permeates this book. Curious because there's a big deal made of naming things, classification — the arbitrariness of it, but the rightness of it, the impossibility of it, but the necessity of it. Where all meaning begins.

"A flat-out fascination with the threat, soberly maintaining that the only thing to do when the world begins to end is to stand aside and paint it. Uncover it. Name it."

There's something — something I can't quite articulate — being said about art here — painting (which figures in the book), literature (by extrapolation), but especially music. It's beyond science, beyond knowing, yet it's key to one's ability to know anything else. Indeed, art and love, those inarticulate things, the only things to really mean anything.

The trick to it:

Zooming in close on the trees, scratching the bark under a microscope, drilling deep inside; and zooming out quick for the forest, a macroscopic blur of colour and movement from far overhead. Seeing both views at the same time. It's something I think I do well in work and in life.

In a minute, he recovered. "The trick to listening," he said, lifting me by the hand, "is to hear the pieces speaking to one another. To treat each one as part of an enormous anatomy still carrying the traces of everything that ever worked, seemed beautiful awhile, became too obvious, and had to be replaced. Music can only mean anything through other music. You have to be able to hear in Stockhausen that homage to the second Viennese school, in Schonberg the rearrangement of sweet Uncle Claude. And every new sleeper that Glass welds together gives new breath to that rococo clockmaker Haydn, as if only now, in 1980, can we at last hear what pleasing the Esterhazys is all about."

Some lessons:

"There are really only two careers that might be of any help. One can either be a surgeon or a musician." Which merits a discussion that leaves me tongue-tied.

"...he is struck by how much repetitive maintenance it takes just to exist. Existence is the cycle extraordinaire; everything tangent, constantly spinning just to stay in place." The everyday we try so hard to rise above is our purpose in life, the whole fucking point.

"One cannot step into the same theme twice."

A puzzle:

In sitting down to write this I thumbed through my copy for asterisked passages. Right at the front is something I meant to come back to.

RLS CMW DJP RFP J?O CEP JJN PRG

ZTS MCJ JEH BLM CRR PLC JCM MEP

JNH JDM RBS J?H BJP PJP SCB TLC

KES REP RCP DTH I?H CRB JSB SDG

I assumed it was a coded epigraph, but it seems it's a dedication, "which, according to Powers, remains unsolved but can be broken using a codex found in the final third of the book." Perhaps I'll crack it before I die. Perhaps it's meant for me.

The effect in toto:

I'll spend weeks to come listening to Bach like I've never listened to him before, and slipping in and out of infinite regress, resampling Godel, Escher, Bach. I will read Poe's The Gold Bug.

The Gold Bug Variations moves me the way Wings of Desire moves me (a favourite film). (I don't mean to draw nonexistent parallels here; the only obvious similarities are in their effect on me.)

(Hmm. Todd as an angel? A muse and a catalyst, outside of time. Who finally falls to earth.)

Variations on a theme, my theme.

He sits wedged in the inseam between wall and floor, listening, thinking that he can hear distant song straining the contour of a variation beyond the variation. He's lost it; accumulated stress pushes him into the realm of imaginary acoustics. But the trace is real, waving the air molecules however faintly. Then he figures it: the pianist singing, caught on record, humming his insufficient heart out. Transcribing the notes from printed page to keypress is not enough. Some ineffable ideal is trapped in the sequence, some further Platonic aria trail beyond the literal fingers to express. Sound that can only approximated, petitioned by this compulsory, angelic, off-key, parallel attempt at running articulation, the thirty-third Goldberg.

There's a thematic resonance: a contemplation of the human experience. How characters refer to each other: in Variations, "Friend"; in Wings, "Compañero." How we assign meaning to meaninglessness. How I hear these works speaking to each other. How we are pure potential.

When the child was a child,

It threw a stick like a lance against a tree,

And it quivers there still today.

The sense of interconnectedness. The awe.

For years, for ever, I was skeptical, but I'm coming round: maybe, in the end, just maybe, love really does conquer all. (What could be simpler?)

Nous sommes embarqués...

Monday, March 05, 2007

And the week passed

So, where were we? The kid was home for a couple days. My hands ached and my feet swelled beyond being able to put on my boots, and I slept fitfully, waking with excruciatingly itchy extremities, blah, blah, blah. The week was ssssoooo dreadfully long, and I was tired the way only aches and pains exacerbated by a small child can hurt, and I read, quite possibly the best book I've ever read, and I wept — it made me weep! — so I didn't get much of anything done, blah, blah, blah. But then my sister visited! and we did nothing (much)! There was big snow and 1500 jigsaw puzzle pieces, plus a few of the kid's puzzles, and a solid half dozen bottles of wine and a crappy movie rental. The kid feverish with cold (again), but finally I could make my hands into fists and my shoes fit. We ate well, and we wandered out to get fresh bagels. The kid sang and danced, and my sister laughed and then she went home. I finished reading my book. And here we are. Everything is normal again.

Doctored answers

After 2 weeks of a 4-year-old's questions:

Is there Doctor Who tonight?

Is there Doctor Who tomorrow?

Will we ever see Rose again?

Will we ever see Doctor Who again?

Where'd the daleks go?

What's a "void"?

Remember how the daleks squished that man's head? Why'd they do that?

Who's the girl in the white dress?

Can we watch Doctor Who?

Finally, some answers: CBC will air Series 3 of Doctor Who beginning June 2007. Presumably it will be preceded by "The Runaway Bride." Torchwood will air in the fall.

Is there Doctor Who tonight?

Is there Doctor Who tomorrow?

Will we ever see Rose again?

Will we ever see Doctor Who again?

Where'd the daleks go?

What's a "void"?

Remember how the daleks squished that man's head? Why'd they do that?

Who's the girl in the white dress?

Can we watch Doctor Who?

Finally, some answers: CBC will air Series 3 of Doctor Who beginning June 2007. Presumably it will be preceded by "The Runaway Bride." Torchwood will air in the fall.

Peggy in blue

Margaret Atwood is to receive the Grand Prix at the 9th edition of the Blue Metropolis Montreal International Literary Festival, which will be held April 25 to 29, 2007.

The Blue Metropolis International Literary Grand Prix is awarded annually to a writer of international stature and accomplishment as a celebration of a lifetime of literary achievement.

The program for this year's festival will be available April 12.

The Blue Metropolis International Literary Grand Prix is awarded annually to a writer of international stature and accomplishment as a celebration of a lifetime of literary achievement.

The program for this year's festival will be available April 12.

Thursday, March 01, 2007

The 50-year-old cat

Fifty years ago today, one of the great masterpieces of American literature was published: The Cat in the Hat, by Dr Seuss (Theodore Geisel), written in response to the problem of Dick and Jane and "why Johnny can't read" (and specifically, John Hersey's suggestion in a 1954 Life magazine article that Dr Seuss write a reading primer), revolutionized how children learn to read.

Happy birthday, Cat in the Hat!

Philip Nel introduces and annotates the Cat in The Annotated Cat: Under the Hats of Seuss and His Cats. The original pages are reproduced of both The Cat in the Hat and The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (a great bonus for me, because I've never read it!), often alongside Seuss's original sketches, colour prototype pages, or author's proofs with Seuss's notes. The annotations also incorporate cartoons that influenced or were influenced by the Cat, illustrations from other Seuss works, and frames from the animated Cat.

The book is brimming with anecdotes and historical tidbits, regarding both Seuss (biographical details) and the times he was writing in (for example, statistics regarding the average household and the book's reception internationally).

Dr Seuss on where he gets his ideas:

This is a be-yoo-tiful book! There's remarkable insight into how a writer works, revises, perfects, as well as into the editorial process as a whole: why the rhymes and rhythms work, how they work in tandem with the layout to compel the reader to turn the page, how pages were combined or broken up to enhance the flow, how the illustrations were tweaked for colour and repetition of line or shape to contribute to emotional effect. Also, the differences between the book and the animated television special (a household favourite) are spelled out, showing how they serve different but complementary interpretations suited to their respective media.

Helena can't read quite yet, but we're working on it!

Tomorrow is Dr Seuss's birthday. Celebrating both the Cat and the good Doctor is Project 236, a (US) nationwide read-aloud of The Cat in the Hat on March 2 at 2:36 (there are only 236 different words in the book).

Send the Cat a birthday card! Random House will donate one children’s book to First Book, an organization that gives books to disadvantaged kids, for every online birthday card received on its website.

Happy birthday, Cat in the Hat!

The sun did not shine

Till the letter carrier came

Bearing a package.

Look! My name!

I sat with Helena.

We sat there, we two.

With a brand new book

We know just what to do.

We looked!

On either side of this big book we sat.

We looked!

And we loved it!

The Annotated Cat!

And we wondered,

"Why, I didn't know that!"

I know it is cold

And the sun is not sunny.

But we can read

This great book that is funny!

Philip Nel introduces and annotates the Cat in The Annotated Cat: Under the Hats of Seuss and His Cats. The original pages are reproduced of both The Cat in the Hat and The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (a great bonus for me, because I've never read it!), often alongside Seuss's original sketches, colour prototype pages, or author's proofs with Seuss's notes. The annotations also incorporate cartoons that influenced or were influenced by the Cat, illustrations from other Seuss works, and frames from the animated Cat.

The book is brimming with anecdotes and historical tidbits, regarding both Seuss (biographical details) and the times he was writing in (for example, statistics regarding the average household and the book's reception internationally).

Dr Seuss on where he gets his ideas:

This is the most asked question of any successful author. Most authors will not disclose their source for fear that other, less successful authors will chisel in on their territory. However, I am willing to take that chance. I get all my ideas in Switzerland near the Forka Pass. There is a little town called Gletch, and two thousand feet up above Gletch there is a smaller hamlet called Uber Gletch. I go there on the fourth of August every summer to get my cuckoo clock repaired. While the cuckoo is in the hospital, I wander around and talk to the people in the streets. They are very strange people, and I get my ideas from them.

This is a be-yoo-tiful book! There's remarkable insight into how a writer works, revises, perfects, as well as into the editorial process as a whole: why the rhymes and rhythms work, how they work in tandem with the layout to compel the reader to turn the page, how pages were combined or broken up to enhance the flow, how the illustrations were tweaked for colour and repetition of line or shape to contribute to emotional effect. Also, the differences between the book and the animated television special (a household favourite) are spelled out, showing how they serve different but complementary interpretations suited to their respective media.

Helena can't read quite yet, but we're working on it!

Tomorrow is Dr Seuss's birthday. Celebrating both the Cat and the good Doctor is Project 236, a (US) nationwide read-aloud of The Cat in the Hat on March 2 at 2:36 (there are only 236 different words in the book).

Send the Cat a birthday card! Random House will donate one children’s book to First Book, an organization that gives books to disadvantaged kids, for every online birthday card received on its website.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)