This is how the story ends:

To the accompaniment of Victor's snoring, Ali-Baba reviewed her life and swallowed the pills. The next morning Victor found her lying facedown on the desk. He read her note and called an ambulance. Paramedics pumped Ali-Baba's stomach, then took her to a mental hospital. Shaking with a hangover, Victor pulled on some clothes and trotted off to work to wait for the liquor store to open.

Ali-Baba was lying in a clean bed in a ward for the insane. She would stay there at least a month. Soon there would be a hot breakfast and conversation with a family doctor. Later, as she knew, her neighbors would swap life stories. Ali-Baba also had a story or two to share. She wanted to tell them, for example, about the first time she took pills, when she went blind for twenty-four hours. The second time put her to sleep for two days, but the sixth time she woke up in the morning fresh as a daisy.

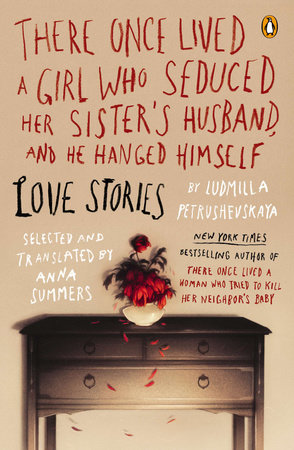

That's how one of the stories ends. But all the stories end like this, just life continuing without end. Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's slim volume of love stories, There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister's Husband, and He Hanged Himself, is brutal and true.

In the introduction, translator Anna Summers writes:

Petrushevskaya's genius as a literary artist lies in her ability to make the strangeness of her mothers, her would-be mothers, her once-were mothers, and her other characters worthy of our sympathy in the partial absence of our understanding. The changes she introduces in vocabulary, perspective, rhythm, and intonation sneak up on us, and before we know it we have implicitly forgive bizarre, bewildering, and often vulgar behaviors and qualities.These stories are small, as small as the lives they depict. Very many of them are forgettable lives. They are also surprisingly light; they waft away.

I read these stories last month, even though my husband had just left me for a younger woman. And they made me feel better. Because other people's lives are so much more tragic than mine. Although, I was drunk for much of the time I was reading.

Life, love — all of it is so inconsequential.

Reviews

A.V. Club

Bookslut

New York Times