The lecture purports to be about images in literature from visual art. Where do writers draw their inspiration? Lessing says we make things too simple; people tend to offer banal answers — composites of acquaintances, a dream, a picture reminds one of a character.

But there must be more to it? Something deeper? That a picture, as an indirect inference, corresponds with one's view of life.

Virginia Woolf describes, she says, an old woman's mind as an opening of doors, letting in a stream of ideas and associations.

With age, space and time become extremely fluid. Every face one encounters reminds one of other faces, in other times and different places.

The webcast is over an hour long, with the first 25 minutes, and then some at the end, devoted to Proust and Vermeer's yellow patch of sunlight.

This is difficult for me to summarize. Lessing rambles and digresses through her mind's labyrinth of associations, and connections are not always evident. Is it contradictory then for me to say what I admire most about her is her straightforwardness? She says what she thinks. And she thinks a great deal.

Mara and Dann is an adventure story (possibly, she confides, soon to be an animated film) with that most classic element of stories found the world over: orphan children.

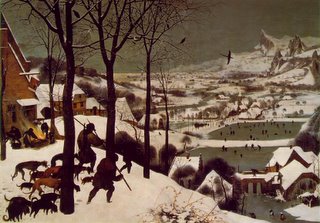

Set in the future, Europe is in an ice age. She pictures it like the mountains in the background of Brueghel's "Hunters in the Snow," a poster of which she has hanging on a door: unnatural and otherworldly, not a real part of Brueghel's countryside, improbable, mythical mountains of snow.

Now there is sequel, The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog.

Mara's daughter looks like this:

Because she does. This painting ("The Parasol," Goya) makes Lessing feel like she's being stroked like a cat.

What strikes me most from this lecture is what she unwittingly divulges about her writing process. She knows the end, knows her characters; she still allows for minor characters to pop up, some unexpected incidents to occur, but she knows where's she going, she knows the shape of the thing. Yet for the first time — remarkably I think, for a woman of 89 years who has published scads of novels — in Griot did a character "take on a life of his own." She always knows how things turn out, but not so with Griot.

(Remarkable, I say, because I read and hear often about writers discussing the ease of writing: characters simply come to life, stories write themselves. I wonder how many of them are lying, what is their motivation in perpetuating the myth of the inspired artist, in denying the hard work; does their reliance on that myth condemn them to lesser accomplishments, relinquish them of the responsibility to do hard work; can they be serious writers?)

So an hour after having raised the question about the source of inspiration, she answers it honestly. Sometimes things come in dreams. How can one know why something draws you, inspires you? But it does. Perhaps one shouldn't ask. "Where do all these things come from? They come from everywhere."

Through all her rambling runs a thread of... melancholy? A weight of the world, a weight of wisdom. And cynicism and even anger (at Alexander the Great, and Banda; how the media is a mechanism in keeping life tame, ordinary, boring; her lost Africa). She talks about humankind's destructive tendencies and her despair if she thinks about it too much — better to pretend it isn't there. And yet. What we destroy, we will rebuild. It won't necessarily be better, but it will persevere.

Lessing would like to be remembered as a hard worker. "Life is really very hard work."

(Why, why, why do I have such a hard time writing about Doris Lessing? It's not for lack of anything to say, it's my inability to break it down, to do so concisely. It's too big somehow. Lessing says, "The human mind, can't stand too much complexity, I've come the conclusion. We have to simplify things." I think she's right, and I think she implies that this is not necessarily the right way to grapple with life, and I agree with that, and this is very much what The Golden Notebook was about for me, insofar as compartmentalizing is an attempt to simplify. Our efforts to simplify often have the opposite effect. Maybe I should stop trying to say anything about Doris Lessing, just delight in the ideas sparked and tangents followed.)

I've not yet read The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog, but I plan to. In case you're wondering, there will not be another book in this story — what happens after this novel leaves off is obvious, and Lessing has nothing more to say about it.

Recent interview: San Francisco Chronicle.

9 comments:

I've not read any Lessing although I constantly peruse her books in my local store and then, unable to choose which one to start first, I walk away empty handed...

Can you recommend a good first one to try?

So, everything associating with everything, surefire rigid youth giving away to too much data, even though we all have an innate love of simplicty, that's the process that's been acting on me. Sounds like an interesting lady. Have you read Albert Goldbarth? He drifts, seemingly yet had that tight point come at circularly too.

Sigh. Oh, Isabella...

After Middlemarch, The Golden Notebook. But I'll try to remember to watch this webcast soon.

I shouldn't come here anymore; you give me too much to think about. :p

As you know, I love Lessing too. I still take my dogeared copy of The Golden Notebook (read many years ago during a heady time when I was full of a lot of ideas..many not my own) off the shelf and just flip through it time to time. I think a re-read might be in the offing. Thank you for pointing the way to this webcast.

I agree with you about writers always dreamily saying the characters write themselves easily on the page. It is this very claim that made me feel certain, for far too many years, that I was not a real writer. My characters don't just show up and dance. It is WORK. Writers who claim otherwise drive me nuts. I do believe, though, there will be a character one day that creates their own destiny and surprises me despite all my planning. Certainly that must happen to writers sometimes...or else where would the myth come from?

I think when authors claim the characters come to life and surprise them, it's intended to impart a kind of mysticism to the process. They come up with ideas, but can't work backwards to find the origin, so they give a bullshit explanation. My mother used to claim god moved her paintbrush. It's the same damn thing.

One of my most common writing experiences is to come up with a story and have every intention of moving forward with it only to have a better idea at the last possible second. In my comic, for example, a possible Lalo-Niesta relationship did not even occur to me until I had drawn that picture of Niesta, looking sad and pretty, in the first chapter. I changed my outline, and it ended up being the emotional centre of the book.

Did the characters themselves do that? No. It was my own little brain.

Heh. I told that to a friend of mine, once, and he said: "Sooo... your brain gets you out of the tight spot it got you into in the first place?!?"

Smart-ass.

I think Rachel's on the right track. While a lot of writers, particularly mystery writers, work from the end of a story, it's silly to think that the characters take on a life of their own.

It is true that as you write, the story seems to unfold around you and the little details about your character start to emerge. However, all of that is part of the process and has nothing to do with them "coming to life."

Conversely, I do believe there are any number of writers who don't put a lot of work into their writing. Though I don't think that's what you were really talking about here.

Kimbofo: I recommend The Fifth Child. It's short and the language quite spare, so the themes (eg, a mother's love, nature vs nurture in a child's character) are all the more haunting and powerful for it. Mara and Dann is my favourite to date, though; don't let "future" put you off (it could just as easily take place thousands of years ago); also, the ecological warnings are subtle.

Diana: I can't think of anyone to whom I'd recommend the Golden Notebook (I'm not sure I know you well enough, but maybe...). I know a few people who read it in school or in their 20s, and didn't see what the big deal is. Me, it came at the right time and place. So read the preface, then read it because you want to, not because you think you should.

Pearl: I'm not familiar with Goldbarth but will look him up.

Callie, Rachel, Tim:

I'm not sure what my point is. Mostly I'm relieved to hear someone admit to the work of it, probably for a couple reasons.

1. My work is frustrating these days (copyediting medical stuff). When scientist non-writers have flashes of writerly inspiration, it's messy, and throws my concept of the process of writing into doubt.

2. I'm grappling with my wanting to want to write, and perhaps like Callie, I'm put off by this myth. Not being someone prone to dreams, flashes of inspiration, or letting things unfold around me, I can see myself more clearly in a writer's role if it IS framed as hard work to make it work. That is, perhaps, as a craft as opposed to an innate talent.

And 3. Yes, Tim, there are a lot of writers who don't put a lot of work into their writing. And it shouldn't be that way. As a reader, I deserve better. And part of me is starting to think I could do it better than many of them.

And Rachel: Poor, poor Lalo! Your brain did a very good job on him.

This is an interesting discussion. I'm not a writer, and when I did try to write (before I realized I was not a writer), I was really awed to discover what hard work it is. I am a painter, however, and I think there are parallels in any creative process. Painting my own work (as opposed to murals, which are collaborative) is an agonizing process, hard hard work and frustration punctuated by sublime periods when what happens on the canvas seems to come into being of its own accord. It is a surprise and a delight when this happens. Maybe that's what writers are talking about when they say a character comes to life? I don't know. But it seems to me there's a lot of work going on in our minds that we're not consciously aware of. I can never just sit down and do a design-- I have a long period at first where I can barely sit at my table. I do laundry. I look at blogs. I dawdle, and pore over art books. And then at some point, I'm able to work, and I think that really I was working all the time, only it was coming together in a place I don't have conscious access to. So I guess, to conclude this long and rambling comment, I think someone doing creative work is a conduit of sorts, but the hard work has to happen first.

Also, thanks Isabella for bringing Doris Lessing to mind again-- I read a lot of her work in my teens and twenties, and what I loved then was just the beauty and purity of the writing. I think now I would better understand what she was writing about. You give me motivation to do some rereading.

Post a Comment