"Each of us narrates our life as it suits us."

I am Elena Ferrante.

To be clear, I am not actually Elena Ferrante. I mean, I am Elena Ferrante, but symbolically, in the way people say Je suis Charlie or how one says We are the Borg. We women, we all are Elena Ferrante.

I had started to formulate this post after I finished the third book of the quartet, but then life happened and suddenly I found myself reading the fourth, and I couldn't break away.

(How

Hillary Clinton is able to ration herself, I can't fathom. I would love nothing more than to hear her speak frankly about this series, and it could be very telling of policy: poverty, corruption, small business, communism, education, women's rights. And on and on.)

I've finished them all now, am still processing them. Wondering what else of Ferrante's to read. Bought a copy of

My Brilliant Friend for a brilliant friend.

Then this weekend, it seems the speculation about

Ferrante's identity may have been put to rest, an individual having been pinpointed on the basis of publishing revenues and real estate transactions (cherchez la femme, follow the money). I think I don't care. What does it matter? So long as she writes more...

I could keep reading and reading. Very cleverly, the first three books end on cliff-hangers. But more than that, they are shape-shifting. Each book is different from its predecessor, but the reading of it also changes your understanding of everything that came before.

The first book is a fairy tale. Ogres and princes, prisons and palaces, communists and poets. A coming-of-age story, with folkloric colour.

The second book is a romance. Love and marriage. Childhood crushes and secret affairs.

The third book is political. A feminist awakening. It was less enjoyable to read; reading it became a compulsion, driven by all that came before, and then an obligation: the adage that the personal is political made manifest. I

had to read it, for my own good, for everyone's.

The fourth book is a reconciliation. A synthesis, a Neapolitan golden notebook. A deconstruction and reconstruction. It is how we live with the hypocrisy of adulthood.

In

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Lenu discovers feminism.

First, intrigued by the title, I read an essay entitled We Spit on Hegel. I read it while Elsa slept in her carriage and Dede, in coat, scarf, and woolen hat, talked to her doll in a low voice. Every sentence struck me, every word, and above all the bold freedom of thought. I forcefully underlined many of the sentences, I made exclamation points, vertical strokes. Spit on Hegel. Spit on the culture of men, spit on Marx, on Engels, on Lenin. And on historical materialism. And on Freud. And on psychoanalysis and penis envy. And on marriage, on family. And on Nazism, on Stalinism, on terrorism. And on war. And on the class struggle. And on the dictatorship of the proletariat. And on socialism. And on Communism. And on the trap of equality. And on all the manifestations of patriarchal culture. And on all its institutional forms. Resist the waste of female intelligence. Deculturate. Disacculturate, starting with maternity, don't give children to anyone. Get rid of the master-slave dialectic. Rip inferiority from our brains. Restore women to themselves. Don't create antitheses. Move on another plane in the name of one's own difference. The university doesn't free women but completes their repression. Against wisdom. While men devote themselves to undertakings in space, life for women on this planet has yet to begin. Woman is the other face of the earth. Woman is the Unpredictable Subject. Free oneself from subjection here, now, in this present. The author of those pages was called Carla Lonzi. How is it possible, I wondered, that a woman knows how to think like that. I worked so hard on books, but I endured them, I never actually used them, I never turned them against themselves. This is thinking. This is thinking against.

And as I read, I'm thinking yes! Yes! I must read Carla Lonzi. I know this all already, I know it instinctively, but here it is articulated so plainly.

And soon I'm reliving my relationships and shaking my head at men.

Maybe there's something mistaken in this desire men have to instruct us; I was young at the time, and I didn't realize that in his wish to transform me was the proof that he didn't like me as I was, he wanted me to be different, or, rather, he didn't want just a woman, he wanted the woman he imagined he himself would be if he were a woman. For Franco, I said, I was an opportunity for him to expand into the feminine, to take possession of it: I constituted the proof of his omnipotence, the demonstration that he knew how to be not only a man in the right way but also a woman. And today when he no longer senses me as part of himself, he feels betrayed.

Reading the third of Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels should have put to rest any speculations that the writer of these novels might be a man. For it to be written by a man would be an insult. But this also speaks to the problem of being unmasked — somehow caught out — by a man.

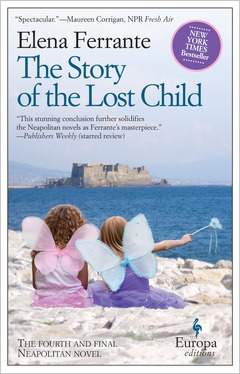

This feminist education is continued in

The Story of the Lost Child.

I talked about my difficult relationship with the feminist groups in Florence and Milan, and, as I did, and experience that I had underestimated suddenly became important: I discovered n public what I had learned by watching that painful effort of excavation. I talked about how, to assert myself, I had always sought to be male in intelligence — I started off every evening saying I felt that I had been invented by men, colonized by their imagination.

So much to relate to: "it seemed to me evident how restrictive, at thirty-two, being a wife and mother might be."

The Story of the Lost Child gets a bit meta. Maybe even metaphysical:

She cited the experience of the earthquake, for more than two years, she had done nothing except complain of how the city had deteriorated. She said that since then she had been careful never to forget that we are very crowded beings, full of physics, astrophysics, biology, religion, soul, bourgeoisie, proletariat, capital, work, profit, politics, many harmonious phrases, many unharmonious, the chaos inside and the chaos outside. So calm down.

Elena is ready to blame the critics, "as if the reviewers hadn't read the book that was in the bookstores but, rather, each had evoked a fantasy book fabricated from his own biases."

This tetralogy is, to put it simplistically, the story of a life-long friendship. But quite apart from how their individual lives are intertwined, apart from the Drama of the Neighbourhood, it's a story of the

idea of friendship. It's about how we reflect each other, how we see ourselves, gauging our ambitions and achievements, wins and losses.

We had become for each other abstract entities, so that now I could invent her for myself both as an expert in in computers and as a determined and implacable urban guerrilla, while she, in all likelihood, could see me both as the stereotype of the successful intellectual and as a cultured and well-off woman, all children, books, and highbrow conversation with an academic husband. We both needed new depth, body, and yet were distant and couldn't give it to each other.

The dissolving margins of the first book in the later volumes are translated as dissolving boundaries. This is the blurring between self and other. Elena and Lila are completely dissolved in each other. "[Lila] perceived herself as a liquid and all her efforts were, in the end, directed only at containing herself." This is both the beauty and the tragedy of the friendship.

I love the slipperiness of the ending. I'd like to believe that the book in my hands is in fact Lila's manuscript, all her research of Naples synthesized and poured into the voice of the Elena she imagines to be trying to define herself in terms of her experience of Lila. We are each others' authors.

I love the ambiguity of the titles of the volumes; they could quite readily apply to either Elena or Lila. Clearly it is Lila who remains in Naples and Elena who has travelled the country, yet Lenu fears that she would stay behind.

Become. It was a verb that had always obsessed me, but I realized it for the first time only in that situation. I wanted to become, even though I had never known what. And I had become, that was certain, but without an object, without a real passion, without a determined ambition. I had wanted to become something — here was the point — only because I was afraid that Lila would become someone and I would stay behind. My becoming was a becoming in her wake. I had to start again to become, but for myself, as an adult, outside of her.

The Story of the Lost Child was somewhat mysterious because for 350 pages there was no obviously lost child. Till that point, the title might've metaphorically been referencing either Elena or Lila, or any one of their children, or all of them, the children of the Neighbourhood, of Naples, of all Italy, lost.

I had a brilliant friend once. Several really, but one in particular, from the age of 11 or so. I kept her letters, from high school and university days. We made very different life choices. In this way I was Elena doing what I was supposed to do but somehow still falling short, and she was Lila doing what she wanted, despite violating societal norms with some catastrophic results, and nobody saw anything but the rightness of her life, the strength of her character. Does everyone have a Lila?

Every night I improvised successfully, starting from my own experience. I talked about the world I came from, about the poverty and squalor, male and also female rages, about Carmen and her bond with her brother, her justifications for violent actions that she would sure never commit. I talked about how, since I was a girl, I had observed in my mother and other women the most humiliating aspects of family life, of motherhood, of subjection to males. I talked about how, for love of a man, one could be driven to be guilty of every possible infamy toward other women, toward children. I talked about my difficult relationship with the feminist groups in Florence and Milan, and, as I did, an experience that I had underestimated suddenly became important: I discovered in public what I had learned by watching that painful effort of excavation. I talked about how, to assert myself, I had always sought to be male in intelligence — I started off every evening saying I felt that I had been invented by men, colonized by their imagination.

[...]

Look, I said to myself, the couple collapses, the family collapses, every cultural cage collapses, every possible social-democratic accommodation collapses, and meanwhile everything tries violently to assume another form that up to now would have been unthinkable: Nino and me, the sum of my children and his, the hegemony of the working class, socialism and Communism, and above all the unforeseen subject, the woman, I. Night after night, I went around recognizing myself in an idea that suggested general disintegration and, at the same time, new composition.

I am Elena Ferrante.

Take note, Senor Gatti, "Unlike stories, real life, when it has passed, inclines toward obscurity, not clarity."

See also

You Want a Piece of Me, by Julianne Ross.