Friday, September 30, 2005

Thursday, September 29, 2005

Re rereads

Survey: how many times have you read War and Peace? Ummm, none.

Forget War and Peace. People are sharing their guilty pleasure books at Culture Vulture — the embarassing books they turn to time and again.

I don't often reread books. (Fairy tales don't count.) Too many books, not enough time.

However, I do find myself rereading children's books. They're so short! — the pay-off in comfort is worth every minute.

A Little Princess — Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Gammage Cup — Carol Kendall

The Chronicles of Narnia — C.S. Lewis

The Little Prince — Antoine de St-Exupery

There's the books I read as a teenager that I later reread critically in university, and perhaps again to satisfy a curiosity or discuss with friends. In this category, 1984, among others.

Other books I dip into (I couldn't begin to list these) to retrieve favourite bits, to flesh out current ideas that somehow make that text relevant (the narrative of life), as a kind of research, or as a refresher to a sequel. But cover to cover, rarely.

I don't really want to reread books (so little time), though sometimes I feel I owe it to my more mature self to better understand some so-called classics.

Yet, for the sheer, if inexplicable, fascination I have with them, I have reread some books countless times:

The Fifth Child — Doris Lessing

The First Century after Beatrice — Amin Maalouf

The Razor's Edge — W. Somerset Maugham

Titus Groan (but not the rest of the Gormenghast trilogy) — Mervyn Peake

Short story:

The Nine Billion Names of God — Arthur C. Clarke

But I don't feel any shame about these.

The only book I've reread (certainly 4 times, if not more), and of which I've owned several copies, having to replace the ones I gave to friends, and that I might not openly confess to: Shibumi, by Trevanian.

Oh! and Michael Moorcock's The Warhound and the World's Pain. I love that book!

Forget War and Peace. People are sharing their guilty pleasure books at Culture Vulture — the embarassing books they turn to time and again.

I don't often reread books. (Fairy tales don't count.) Too many books, not enough time.

However, I do find myself rereading children's books. They're so short! — the pay-off in comfort is worth every minute.

A Little Princess — Frances Hodgson Burnett

The Gammage Cup — Carol Kendall

The Chronicles of Narnia — C.S. Lewis

The Little Prince — Antoine de St-Exupery

There's the books I read as a teenager that I later reread critically in university, and perhaps again to satisfy a curiosity or discuss with friends. In this category, 1984, among others.

Other books I dip into (I couldn't begin to list these) to retrieve favourite bits, to flesh out current ideas that somehow make that text relevant (the narrative of life), as a kind of research, or as a refresher to a sequel. But cover to cover, rarely.

I don't really want to reread books (so little time), though sometimes I feel I owe it to my more mature self to better understand some so-called classics.

Yet, for the sheer, if inexplicable, fascination I have with them, I have reread some books countless times:

The Fifth Child — Doris Lessing

The First Century after Beatrice — Amin Maalouf

The Razor's Edge — W. Somerset Maugham

Titus Groan (but not the rest of the Gormenghast trilogy) — Mervyn Peake

Short story:

The Nine Billion Names of God — Arthur C. Clarke

But I don't feel any shame about these.

The only book I've reread (certainly 4 times, if not more), and of which I've owned several copies, having to replace the ones I gave to friends, and that I might not openly confess to: Shibumi, by Trevanian.

Oh! and Michael Moorcock's The Warhound and the World's Pain. I love that book!

Tuesday, September 27, 2005

Brief

Stephen Hawking interviewed on his new book, A Briefer History of Time.

To my delight:

To my delight:

He is working on a children's book about relativity with his daughter Lucy, because children are the best audience: "Naturally interested in space and not afraid to ask why."

The other, stupid, book I've been reading

The review caught my attention, made me jot down the title and, eventually, recently buy it. (In truth, the purchase was a bit of a mistake. I clicked Confirm without reviewing my order. The book was not in fact on my must-read-now-and-at-any-cost list, but on the I'll-get-to-it-someday list, and a proper review of my order would've postponed this purchase for a month or two. Let this be a lesson to me. But at least now, I've gotten it over with.)

Ugh.

While the premise of Glyph, by Percival Everett, is indeed playful, the humour of its execution wears thin within a couple dozen pages. "Genius" (or "accelerated") baby Ralph reads at a more advanced level than I do, but he chooses to remain mute. He becomes an object of scientific study, and is kidnapped, then again, and again. He narrates his story as a 4-year-old, applying a deconstructive reading to his experience, grappling with semiotics and psychology.

Footnotes everywhere, most of them unnecessary. Diagrams. And really bad poetry.

Very tedious. And it makes me feel stupid. Not subtle. I can't really appreciate an author who makes me feel stupid. Not clever.

I read a lot of literary experiments, games, in my university days, but I no longer have time for this shit.

Ugh.

While the premise of Glyph, by Percival Everett, is indeed playful, the humour of its execution wears thin within a couple dozen pages. "Genius" (or "accelerated") baby Ralph reads at a more advanced level than I do, but he chooses to remain mute. He becomes an object of scientific study, and is kidnapped, then again, and again. He narrates his story as a 4-year-old, applying a deconstructive reading to his experience, grappling with semiotics and psychology.

Footnotes everywhere, most of them unnecessary. Diagrams. And really bad poetry.

Very tedious. And it makes me feel stupid. Not subtle. I can't really appreciate an author who makes me feel stupid. Not clever.

I read a lot of literary experiments, games, in my university days, but I no longer have time for this shit.

Monday, September 26, 2005

My very long weekend

J-F was away the last few days — his annual fishing weekend with the boys.

Questions

How can having sole charge of a toddler for more than 24 hours at a time be so exhausting yet so refreshing at the same time?

Better to let her have her own seat on the Metro while tired rush-hour commuters look on resentfully, or give up one (or both) of our seats and let everyone endure a tanrum for the duration of our journey?

Why does Helena not see delicately herbed tomato pizza as a treat, the way I do?

Why is it that I so rarely can muster the energy to be motivated enough to be at the park at 8 in the morning when J-F is around?

How is that I fail to get a proper night's sleep when it's even more important that I be properly rested?

Highlights

The park! All to ourselves! Allowed her to experiment on the big-kid climbing apparatus, tackle the big slide.

Shopping! Fresh air! Exercise! Early bedtimes for her, late nights of reading in bed for me.

I enjoyed the privilege of dropping off and picking up Helena at daycare on Friday. When we got there, Helena didn't want me to leave. What the hell. I stayed about an hour, through snacktime. The educatrice was trying to get everyone excited about going to the park for the rest of the morning. One little girl said she wanted to nap, and all the others thought this was a great idea. (But they were eventually dragged off to the park anyway, and had great fun.) Snack finished, Helena reached for a jigsaw puzzle and didn't blink when I left.

Drop-off and pick-up is J-F's task. The daycare is, after all, across the street from his place of employment. Too, I always looked at this arrangement as their ritual quality time together. But sometimes I feel like I'm missing out.

Vacation's over now. Back to normal.

Questions

How can having sole charge of a toddler for more than 24 hours at a time be so exhausting yet so refreshing at the same time?

Better to let her have her own seat on the Metro while tired rush-hour commuters look on resentfully, or give up one (or both) of our seats and let everyone endure a tanrum for the duration of our journey?

Why does Helena not see delicately herbed tomato pizza as a treat, the way I do?

Why is it that I so rarely can muster the energy to be motivated enough to be at the park at 8 in the morning when J-F is around?

How is that I fail to get a proper night's sleep when it's even more important that I be properly rested?

Highlights

The park! All to ourselves! Allowed her to experiment on the big-kid climbing apparatus, tackle the big slide.

Shopping! Fresh air! Exercise! Early bedtimes for her, late nights of reading in bed for me.

I enjoyed the privilege of dropping off and picking up Helena at daycare on Friday. When we got there, Helena didn't want me to leave. What the hell. I stayed about an hour, through snacktime. The educatrice was trying to get everyone excited about going to the park for the rest of the morning. One little girl said she wanted to nap, and all the others thought this was a great idea. (But they were eventually dragged off to the park anyway, and had great fun.) Snack finished, Helena reached for a jigsaw puzzle and didn't blink when I left.

Drop-off and pick-up is J-F's task. The daycare is, after all, across the street from his place of employment. Too, I always looked at this arrangement as their ritual quality time together. But sometimes I feel like I'm missing out.

Vacation's over now. Back to normal.

What I read this weekend

Dante's Equation, by Jane Jensen.

A missing manuscript by a Jewish mystic who vanished from Auschwitz.

The study of Torah code.

Quantum physics and a mathematical equation for the universal forces of "good" and "evil."

I eat that stuff up.

Dante's Equation has the additional draw, for me, of alternate universes. Throw in a government operative who monitors scientific research for potential weapons technology.

Many reviews liken the elements of Dante's Equation — a thriller built around religious symbology — to Dan Brown's The DaVinci Code (which I enjoyed, if only because of those "religious" elements). The comparison is fair (Jensen told in her Grail Templar conspiracy story in another medium years ago). The writing is, to be polite about it, inelegant.

The characters are mostly unlikeable, but this in fact serves a purpose in the second half of the book. At that point, the physical laws of the universe sort the characters off to alien worlds that reflect their truest natures, their own personal heaven-hell, from which they all emerge in the end, perhaps too neatly, enlightened.

As one review notes:

Another review points out some shortcomings:

There's so little science talk in this novel, I can't say I noticed. And I don't really care. The ideas are still pretty cool.

Excerpt.

A missing manuscript by a Jewish mystic who vanished from Auschwitz.

The study of Torah code.

Quantum physics and a mathematical equation for the universal forces of "good" and "evil."

I eat that stuff up.

Dante's Equation has the additional draw, for me, of alternate universes. Throw in a government operative who monitors scientific research for potential weapons technology.

Many reviews liken the elements of Dante's Equation — a thriller built around religious symbology — to Dan Brown's The DaVinci Code (which I enjoyed, if only because of those "religious" elements). The comparison is fair (Jensen told in her Grail Templar conspiracy story in another medium years ago). The writing is, to be polite about it, inelegant.

The characters are mostly unlikeable, but this in fact serves a purpose in the second half of the book. At that point, the physical laws of the universe sort the characters off to alien worlds that reflect their truest natures, their own personal heaven-hell, from which they all emerge in the end, perhaps too neatly, enlightened.

As one review notes:

Jane Jensen is careful to make clear that "good" and "evil", with all their moral baggage, are subjective concepts, while the universal forces these ideas reflect are simply physical laws, devoid of moral weight. Also, for all the lavish employment of religious imagery, she is wise enough to leave relative the question of God. While Aharon finds in his experience a new and restored faith, to Jill it's all about science.

Another review points out some shortcomings:

For any reader who has some basic knowledge of quantum mechanics or wave theory, the scientific concepts that represent the core of the book are ludicrous mumbo jumbo. It is also annoying in an SF novel for the author not to know the difference between a bacterium and a virus, or not know that rotting fruits are not dying but being consumed by microorganisms. It is also annoying for the scientists not to express surprise that Torah code provides insights into quantum physics and future history.

There's so little science talk in this novel, I can't say I noticed. And I don't really care. The ideas are still pretty cool.

Excerpt.

Mind your language

Today: European Day of Languages 2005 (being also a day featuring European languages). "The Day aims to encourage language learning among all age groups, to emphasise the importance of diversifying language learning, and to foster respect for all of Europe’s languages, including those spoken in regions and by minorities."

Quiz, in 6 thematic areas (general; scripts and writing; etymology; countries and languages; language families; miscellaneous), in which you may learn how much you don't know.

Interactive game: official languages of Europe.

Say "hello."

See The Literary Saloon for links to articles on second-language stats and rankings.

Quiz, in 6 thematic areas (general; scripts and writing; etymology; countries and languages; language families; miscellaneous), in which you may learn how much you don't know.

Interactive game: official languages of Europe.

Say "hello."

To be monolingual is to be dependent on the linguistic competence, and goodwill, of others. Learning to use another language is about more than the acquisition of a useful skill — it reflects an attitude, of respect for the identity and culture of others and tolerance of diversity.

See The Literary Saloon for links to articles on second-language stats and rankings.

Friday, September 23, 2005

The Snow Queen, and more

I did re-read Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen and, while I'm sure I could read many other fairytales in ways that tell me about my world, this one suits me well.

One translation begins simply: "When we are at the end of the story, we shall know more than we know now." Words to live by.

From Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen (from the first part, of seven):

That's the version I pulled off my shelf yesterday. The Polish version, unsurprisingly, maintains the same references to angels; the demon nears not only the heavens, but God himself. But checking another English edition (yes, I have many books of fairytales) I find the demon is a wicked magician, the "grins" in the mirror are "wrinkles." Elsewhere a goblin. Yet another secular version (online) features a wicked sprite who flies up to the stars.

I note now that the demon keeps a school. Their "education" is filtered. Know thy source.

How it frames my worldview:

That people are inherently good. Evil acts have an external source, in experience and environment.

That when one loses focus, strays from one's task, it is owing to treachery and deceit. Even then, the heart remains true.

That everyone, everything (the river, the flowers, the sparrows), "knows" things, but we cannot expect them to know things beyond their experience.

The power of tears to clear one's vision.

The seductive power of snow. The witch of that book with the lion and the wardrobe is surely based in this queen.

The universal experience of reading The Snow Queen (from Deborah Eisenberg as quoted here):

How it ends:

Someone else's Snow Queen life.

More on Little Red Riding Hood:

Read about Crane Maiden at Pratie Place.

One translation begins simply: "When we are at the end of the story, we shall know more than we know now." Words to live by.

From Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen (from the first part, of seven):

You must attend to the commencement of this story, for when we get to the end we shall know more than we do now about a very wicked hobgoblin; he was one of the very worst, for he was a real demon. One day, when he was in a merry mood, he made a looking-glass which had the power of making everything good or beautiful that was reflected in it almost shrink to nothing, while everything that was worthless and bad looked increased in size and worse than ever. The most lovely landscapes appeared like boiled spinach, and the people became hideous, and looked as if they stood on their heads and had no bodies. Their countenances were so distorted that no one could recognize them, and even one freckle on the face appeared to spread over the whole of the nose and mouth. The demon said this was very amusing. When a good or pious thought passed through the mind of any one it was misrepresented in the glass; and then how the demon laughed at his cunning invention. All who went to the demon’s school — for he kept a school — talked everywhere of the wonders they had seen, and declared that people could now, for the first time, see what the world and mankind were really like. They carried the glass about everywhere, till at last there was not a land nor a people who had not been looked at through this distorted mirror. They wanted even to fly with it up to heaven to see the angels, but the higher they flew the more slippery the glass became, and they could scarcely hold it, till at last it slipped from their hands, fell to the earth, and was broken into millions of pieces. But now the looking-glass caused more unhappiness than ever, for some of the fragments were not so large as a grain of sand, and they flew about the world into every country. When one of these tiny atoms flew into a person’s eye, it stuck there unknown to him, and from that moment he saw everything through a distorted medium, or could see only the worst side of what he looked at, for even the smallest fragment retained the same power which had belonged to the whole mirror. Some few persons even got a fragment of the looking-glass in their hearts, and this was very terrible, for their hearts became cold like a lump of ice. A few of the pieces were so large that they could be used as window-panes; it would have been a sad thing to look at our friends through them. Other pieces were made into spectacles; this was dreadful for those who wore them, for they could see nothing either rightly or justly. At all this the wicked demon laughed till his sides shook—it tickled him so to see the mischief he had done. There were still a number of these little fragments of glass floating about in the air, and now you shall hear what happened with one of them.

That's the version I pulled off my shelf yesterday. The Polish version, unsurprisingly, maintains the same references to angels; the demon nears not only the heavens, but God himself. But checking another English edition (yes, I have many books of fairytales) I find the demon is a wicked magician, the "grins" in the mirror are "wrinkles." Elsewhere a goblin. Yet another secular version (online) features a wicked sprite who flies up to the stars.

I note now that the demon keeps a school. Their "education" is filtered. Know thy source.

How it frames my worldview:

That people are inherently good. Evil acts have an external source, in experience and environment.

That when one loses focus, strays from one's task, it is owing to treachery and deceit. Even then, the heart remains true.

That everyone, everything (the river, the flowers, the sparrows), "knows" things, but we cannot expect them to know things beyond their experience.

The power of tears to clear one's vision.

The seductive power of snow. The witch of that book with the lion and the wardrobe is surely based in this queen.

The universal experience of reading The Snow Queen (from Deborah Eisenberg as quoted here):

The febrile clarity and propulsion [of the story] is accomplished at the expense of the reader's nerves. Especially taxing are the claims on the reader by both Kay and Gerda. Who has not, like Gerda, been exiled from the familiar comforts of one's world by the departure or defection of a beloved?

And what child has not been confounded by the daily employment of impossible obstacles and challenges? Who has not been forced to accede to a longing that nothing but its object can allay? On the other hand, who has not experienced some measure or some element of Kay's despair? Who has not, at one time or another, been paralyzed and estranged as his appetite and affection for life leaches away? . . . Who has not, at least briefly, retreated into a shining hermetic fortress from which the rest of the world appears frozen and colorless? Who has not courted an annihilating involvement? Who has not mistaken intensity for significance? What devotee of art has not been denied art's blessing? And who, withholding sympathy from his unworthy self, has not been ennobled by the sympathy of a loving friend?

How it ends:

But Gerda and Kay went hand-in-hand towards home . . . They went upstairs into the little room, where all looked just as it used to do. The old clock was going “tick, tick,” and the hands pointed to the time of day, but as they passed through the door into the room they perceived that they were both grown up, and become a man and woman. . . And they both sat there, grown up, yet children at heart; and it was summer, — warm, beautiful summer.

Someone else's Snow Queen life.

More on Little Red Riding Hood:

Beauty, horror, wonders, violence, and magic have always tumbled thick and fast through fairy tales. Folk raconteurs gave their audiences what they wanted, indulging the desire for audacious eroticism, hyperbolic fantasies, and casual cruelty. For those gathered around the hearth, Little Red Riding Hood was not necessarily an innocent who strays from the forest path. In tales that formed part of an adult storytelling culture in premodern France, she unwittingly feasts on the flesh and blood of her grandmother, performs an elaborate striptease for the wolf, and manages to escape by telling the predatory beast that she needs to go outdoors to relieve herself. Firmly rooted in the familiar, she introduces us to the great existential mysteries, in a miniature and manageable form. Her irreverent behavior, effortless mobility, willingness to take detours, and daring resourcefulness modeled possibilities for those lingering at the fireside.

Read about Crane Maiden at Pratie Place.

Thursday, September 22, 2005

Fairytales

An exploration of the fairytales underlying A.S. Byatt's short stories.

Said article is fairly academic and, well, boring (and, frankly, I prefer Byatt's novels to her short stories, but I prefer novels in general over short stories) — and I've had far too little coffee yet this morning to be able to process it — but this jumped out at me:

My mother's favourite fairy tale is Little Red Riding Hood. Perhaps it speaks to her worldview, or to her deepest, darkest, truest self, more than I ever previously considered. A journey, a task, beset by danger; a naive initiated into adulthood. Perhaps her affinity for this tale is purely sentimental, as the one she remembers most distinctly her mother telling her. But it may have taken on larger significance when her childhood was interrupted by war in Poland in 1939 and treacherous journeys ensued.

(If I asked her what her second favourite story is, I'm certain she would tell me The Little Match Girl.)

My sentimental favourite is Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen. It was read to me in Polish, and I was affected by the accompanying illustrations by J.M. Szancer as much as by the story itself. (The book was my sister's, but she's now bestowed it on Helena.) I'm inspired to re-read it now to know what it tells me about my world.

My sentimental favourite is Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen. It was read to me in Polish, and I was affected by the accompanying illustrations by J.M. Szancer as much as by the story itself. (The book was my sister's, but she's now bestowed it on Helena.) I'm inspired to re-read it now to know what it tells me about my world.

What fairytale are you?

Said article is fairly academic and, well, boring (and, frankly, I prefer Byatt's novels to her short stories, but I prefer novels in general over short stories) — and I've had far too little coffee yet this morning to be able to process it — but this jumped out at me:

Byatt reveals her concept of fairytale images as a way of understanding the working of imagination: "You can understand a lot about yourself by working out which fairytale you use to present your world to yourself in."

My mother's favourite fairy tale is Little Red Riding Hood. Perhaps it speaks to her worldview, or to her deepest, darkest, truest self, more than I ever previously considered. A journey, a task, beset by danger; a naive initiated into adulthood. Perhaps her affinity for this tale is purely sentimental, as the one she remembers most distinctly her mother telling her. But it may have taken on larger significance when her childhood was interrupted by war in Poland in 1939 and treacherous journeys ensued.

(If I asked her what her second favourite story is, I'm certain she would tell me The Little Match Girl.)

My sentimental favourite is Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen. It was read to me in Polish, and I was affected by the accompanying illustrations by J.M. Szancer as much as by the story itself. (The book was my sister's, but she's now bestowed it on Helena.) I'm inspired to re-read it now to know what it tells me about my world.

My sentimental favourite is Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen. It was read to me in Polish, and I was affected by the accompanying illustrations by J.M. Szancer as much as by the story itself. (The book was my sister's, but she's now bestowed it on Helena.) I'm inspired to re-read it now to know what it tells me about my world.What fairytale are you?

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

Nominibus suis

I was never any good at naming things. My childhood toys bore such imaginative monikers as "Teddy." One rust-coloured bear went by the it-sounds-slightly-more-like-a-real name "Rusty," but even then, though I'd had him from birth, the name wasn't fixed till a good ten years on.

When I was 7, my sister brought home a kitten. Apparently she tried out the prog-rock-inspired handle Talybont (I only learned of this in recent years). But I, and the rest of the family and neighbours, so easily swayed by a 7-year-old's pronouncements, knew him as Blacky.

(I might've been 6. Blacky came to an early and tragic end, news of which was delivered to our door by a neighbour, while we were waiting for our pizza (what a treat!) to arrive.)

When I was 25 another black kitten came into my life. While I aspired to something more evocative than "Blacky," weeks passed before anything stuck. Still, many consider naming a pet for a favourite author precious.

Cat number 2 (Blur reference aside, not her real name) was adopted from the Humane Society. Fortunately, she already had a name, even if it is kind of stupid.

Arguably, the naming of my child was an exception amid my sorry history. However, while Helena's name had been "chosen" weeks beforehand, I fought committing it to paper for days after her birth. I was waiting to know that it suited her, looking for a sign of confirmation from her that she liked it, that it spoke to her essence.

I'm not comfortable with naming Helena's toys. My track record provides ample enough reason for me to shy away from this responsibility. And I do see it as a responsibility. They're her toys after all — it's her right to designate the essential.

Many stuffed toys come pre-named these days. Only rarely do name and object feel like a proper match. Peanut the teddybear is one of these rarities. For some reason, only the giraffe who awaited Helena's arrival and the elephant who showed up later readily gave up their sewn-in labels to become, respectively, Ginger and Fred (named — by me! — without thought for their pairing, but it's a happy fit). All the others are blank slates.

I wonder how christenings transpire in other households. Is it a parent's spontanous blurt? Is it a child's naive babble? Do families consult on the matter?

Umberto Eco in The Search for the Perfect Language:

Which is it?

I've asked Helena about her creature's names. She shows as much creativity as I ever did. Her cheval is Horsey, one chien is Puppy. Her dolls, all of them, are Lala (which is the Polish word for, you guessed it, "doll"). They have temperaments and preferences, individual routines and distinct styles, but no names.

At long last, I am pleased to announce that Helena, after much deliberation on the dozens of suggestions proferred by J-F and myself, has named two of her toys. Over the course of the first day, they switched identities a few times, but in the last week they have become firmly established. The bear and the (space!) dog: respectively, Tolstoy and Buzz.

When I was 7, my sister brought home a kitten. Apparently she tried out the prog-rock-inspired handle Talybont (I only learned of this in recent years). But I, and the rest of the family and neighbours, so easily swayed by a 7-year-old's pronouncements, knew him as Blacky.

(I might've been 6. Blacky came to an early and tragic end, news of which was delivered to our door by a neighbour, while we were waiting for our pizza (what a treat!) to arrive.)

When I was 25 another black kitten came into my life. While I aspired to something more evocative than "Blacky," weeks passed before anything stuck. Still, many consider naming a pet for a favourite author precious.

Cat number 2 (Blur reference aside, not her real name) was adopted from the Humane Society. Fortunately, she already had a name, even if it is kind of stupid.

Arguably, the naming of my child was an exception amid my sorry history. However, while Helena's name had been "chosen" weeks beforehand, I fought committing it to paper for days after her birth. I was waiting to know that it suited her, looking for a sign of confirmation from her that she liked it, that it spoke to her essence.

I'm not comfortable with naming Helena's toys. My track record provides ample enough reason for me to shy away from this responsibility. And I do see it as a responsibility. They're her toys after all — it's her right to designate the essential.

Many stuffed toys come pre-named these days. Only rarely do name and object feel like a proper match. Peanut the teddybear is one of these rarities. For some reason, only the giraffe who awaited Helena's arrival and the elephant who showed up later readily gave up their sewn-in labels to become, respectively, Ginger and Fred (named — by me! — without thought for their pairing, but it's a happy fit). All the others are blank slates.

I wonder how christenings transpire in other households. Is it a parent's spontanous blurt? Is it a child's naive babble? Do families consult on the matter?

Umberto Eco in The Search for the Perfect Language:

'Out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them'. The interpretation of this passage is an extremely delicate matter. Clearly we are here in the presence of a motif, common to other religions and mythologies — that of the nomothete, the name-giver, the creator of language. Yet it is not at all clear on what basis Adam actually chose the names he gave to the animals. The version in the Vulgate, the source for European culture's understaning of the passage, does little to resolve this mystery. The Vulgate has Adam calling the vaious animals 'nominibus suis', which we can only translate, 'by their own names'. The King James version does not help us any more: 'Whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.' But Adam might have called the animals 'by their own names' in two senses. Either he gave them the names that, by some extra-linguistic right, were already due to them, or he gave them those names we still use on the basis of a convention initiated by Adam. In other words, the names that Adam gave the animals are either the names that each animal intinsically ought to have been given, or simply the names that the nomothete arbitrarily and ad placitum decided to give to them.

Which is it?

I've asked Helena about her creature's names. She shows as much creativity as I ever did. Her cheval is Horsey, one chien is Puppy. Her dolls, all of them, are Lala (which is the Polish word for, you guessed it, "doll"). They have temperaments and preferences, individual routines and distinct styles, but no names.

At long last, I am pleased to announce that Helena, after much deliberation on the dozens of suggestions proferred by J-F and myself, has named two of her toys. Over the course of the first day, they switched identities a few times, but in the last week they have become firmly established. The bear and the (space!) dog: respectively, Tolstoy and Buzz.

Tuesday, September 20, 2005

Les Deux Magots

In The New Yorker, "The strange liaison of Sartre and Beauvoir," by Louis Menand. "He liked to drink and talk all night, and so did she."

The first time I saw Paris, I had 52 hours from debarkation to boarding for home again. Very little time was spent sleeping. Drinking, dining, dancing, but mostly walking, breathing, walking.

It wasn't exactly a pilgrimage, and I'm not entirely sure what my inspiration was, but for all the glorious things to see and do in Paris, it was for some reason a priority for me to visit, of all things, not the Eiffel Tower or the Louvre, not even the touristy gravesides of the inhabitants of Père Lachaise cemetery, but the site of the remains of Jean-Paul and Simone in Montparnasse, stopping to have a drink in their honour at Les Deux Magots.

I'd studied philosophy, but by then I'd pretty much given it up as dead. I realized I was more interested in literature as a derivative of philosophical though (and interested in pursuing neither as a career). I'd been through a phase, reading all of their fiction I could get my hands on. I'd also read The Second Sex.

I enjoyed the novels, not least because of the obviousness of de Beauvoir's romans a clef. Not anything they wrote or said had the impact on me of the example of how they lived their life, particularly their emotional, romantic, sexual life. Together. Apart but still together. Buried together.

In many ways, then, in my early twenties, I likened myself to de Beauvoir; I embarked on experiments rather than relationships, exercising seuxual politics, looking for an intellectual and emotional equal (equally average, that is), looking for my Sartre. I came close, I think, a couple times.

(I'm considering revisiting some of those novels I read. Reading Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook this summer jarred me into some kind of new consciousness — though, no, I can't bring myself to write about it just yet — of my place as a consequence of the experiences, primarily emotional, that formed me, not least drinking and talking all night. This recollection is part of that. My bed is very different from what I once thought it would be.)

It still fascinates: Apart but still together. Buried together.

The Second Sex (English translation).

Simone de Beauvoir, portrait.

The first time I saw Paris, I had 52 hours from debarkation to boarding for home again. Very little time was spent sleeping. Drinking, dining, dancing, but mostly walking, breathing, walking.

It wasn't exactly a pilgrimage, and I'm not entirely sure what my inspiration was, but for all the glorious things to see and do in Paris, it was for some reason a priority for me to visit, of all things, not the Eiffel Tower or the Louvre, not even the touristy gravesides of the inhabitants of Père Lachaise cemetery, but the site of the remains of Jean-Paul and Simone in Montparnasse, stopping to have a drink in their honour at Les Deux Magots.

I'd studied philosophy, but by then I'd pretty much given it up as dead. I realized I was more interested in literature as a derivative of philosophical though (and interested in pursuing neither as a career). I'd been through a phase, reading all of their fiction I could get my hands on. I'd also read The Second Sex.

I enjoyed the novels, not least because of the obviousness of de Beauvoir's romans a clef. Not anything they wrote or said had the impact on me of the example of how they lived their life, particularly their emotional, romantic, sexual life. Together. Apart but still together. Buried together.

In many ways, then, in my early twenties, I likened myself to de Beauvoir; I embarked on experiments rather than relationships, exercising seuxual politics, looking for an intellectual and emotional equal (equally average, that is), looking for my Sartre. I came close, I think, a couple times.

With the publication of "Letters to Sartre," it was clear that, privately, he and Beauvoir held most of the people in their lives in varying degrees of contempt. They enjoyed, especially, recounting to each other the lies they were telling.

(I'm considering revisiting some of those novels I read. Reading Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook this summer jarred me into some kind of new consciousness — though, no, I can't bring myself to write about it just yet — of my place as a consequence of the experiences, primarily emotional, that formed me, not least drinking and talking all night. This recollection is part of that. My bed is very different from what I once thought it would be.)

But it is clear now that Sartre and Beauvoir did not simply have a long-term relationship supplemented by independent affairs with other people. The affairs with other people formed the very basis of their relationship. The swapping and the sharing and the mimicking, the memoir- and novel-writing, right down to the interviews and the published letters and the duelling estates, was the stuff and substance of their "marriage." This was how they slept with each other after they stopped sleeping with each other.

It still fascinates: Apart but still together. Buried together.

The Second Sex (English translation).

Simone de Beauvoir, portrait.

Sunday, September 18, 2005

What were you expecting?

What to Expect When You're Expecting was my pregnancy bible. When I learned I was pregnant, I hied me to a bookstore and hung out there for a few hours, checking out all that was on offer. Then I bought me one. Just one. One single solitary pregnancy book. (And a Lemony Snicket volume.)

It seems many people don't like the book nearly as much as I did.

Maybe cuz I'm not a very touchy-feely wonder-of-childbirth kind of person. Maybe cuz I rather enjoy considering worst case scenarios. Yet I still basked in the glow of pregnancy. I like information.

No doubt, the book requires regular updating to adjust for scientific advances as well as for society's sensibilites.

However, what truly shocks me is that someone might purchase a title (nonfiction — a manual! for pregnancy! not exactly a one-size-fits-all experience) based on some expert's recommendation without having a clue what might be inside, without cracking the cover, without having achieved a personal confidence that "this book is right for me."

(Based on my "success" with this book, I got myself the follow-up What to Expect the First Year, but I never did read the whole thing. Mostly I'm just winging this child-rearing thing. With a little help from my blogging buddies.)

It seems many people don't like the book nearly as much as I did.

[I]n its third decade the book has turned into a publishing conundrum: It is the most popular and widely trusted book in its category and yet is coming under such regular criticism that its authors are revising some of its key tenets. The reaction comes in part from expecting parents who call it a worst-case-scenario handbook. (Nicknames include "What to Freak Out About When You Are Expecting" and "What to Expect if You Want to Develop an Eating Disorder.") Though many parents swear by it, a startling number protest that, instead of emphasizing the wondrous process of fetal development, the book dwells mostly on complications, including the pedestrian (anemia), the more exotic ("incompetent cervix") and a catalog of horrors at the book's end ("uterine rupture").

Maybe cuz I'm not a very touchy-feely wonder-of-childbirth kind of person. Maybe cuz I rather enjoy considering worst case scenarios. Yet I still basked in the glow of pregnancy. I like information.

No doubt, the book requires regular updating to adjust for scientific advances as well as for society's sensibilites.

However, what truly shocks me is that someone might purchase a title (nonfiction — a manual! for pregnancy! not exactly a one-size-fits-all experience) based on some expert's recommendation without having a clue what might be inside, without cracking the cover, without having achieved a personal confidence that "this book is right for me."

(Based on my "success" with this book, I got myself the follow-up What to Expect the First Year, but I never did read the whole thing. Mostly I'm just winging this child-rearing thing. With a little help from my blogging buddies.)

Friday, September 16, 2005

What the wise man says

Review of the Dalai Lama's new book, The Universe in a Single Atom: The Convergence of Science and Spirituality.

"If scientific analysis were conclusively to demonstrate certain claims in Buddhism to be false, then we must accept the findings of science and abandon those claims," he writes. No one who wants to understand the world "can ignore the basic insights of theories as key as evolution, relativity and quantum mechanics."

Book buying

For education!

I received an email some time ago asking me to help promote booksXYZ. It sounds like a worthwhile endeavour (though I was unable to establish how funds from purchases from Canadians are distributed).

From the press release:

Note that the organization is based in Louisiana; existing resources are aiding schools affected by Hurricane Katrina.

For fun!

Buy a Friend a Book! week, during which one is to buy a book for a friend for no good reason, is fast approaching:

I received an email some time ago asking me to help promote booksXYZ. It sounds like a worthwhile endeavour (though I was unable to establish how funds from purchases from Canadians are distributed).

From the press release:

booksXYZ.com, an innovative on-line bookstore sends all profits to education, and 5% of each purchase goes to the school of the customer’s choice. All 120,000 U.S. schools, public and private, kindergarten through college, are included on the website. booksXYZ currently lists over 1.4 million titles and adds more constantly.

booksXYZ is owned by The American Public School Endowments and its affiliate and founding entity, The Acadiana Educational Endowment; both are 501(c)3 non-profit organizations. The AEE was founded in 1989 and has distributed over $200,000 to public education.

Note that the organization is based in Louisiana; existing resources are aiding schools affected by Hurricane Katrina.

For fun!

Buy a Friend a Book! week, during which one is to buy a book for a friend for no good reason, is fast approaching:

Spread the word by blogging about your choice of book and book recipient. Look at me, you'll be saying to your site's visitors, I am the sort of person who buys gifts for my friends for no good reason. Befriend me! Love me! Read me.

Thursday, September 15, 2005

Belonging

The Star of Kazan, by Eva Ibbotson. I read a review of this book more than a year ago. I often save reviews, but not this one. I don't recall a thing the review said, but it must've been good. I jotted down the title, and, finally, early last week it arrived on my doorstep.

(It came in a box with a large assortment of other literary delights. Embarrassingly large. I ripped through the cardboard, stashed the contents under my side of the bed, and dismantled the box, hurriedly stuffing it and the wrapping material in the recycle bin, which fortunately was already on the curb awaiting pick-up — all traces gone, before J-F returned home from work.)

The Star of Kazan has all the classic elements of a classic children's tale, and then some:

Perhaps most importantly, it features a cast of kindly characters with imagination and dreams, and a love and respect for truth and books. And some villains who are pretty nasty. What's not to love!?

This is an adventure showcasing courage in the face of great adversity.

In brief (from School Library Journal):

It seems to me that the best children's books feature orphans. At the very least, the parents are out of sight. What child doesn't sometimes wonder what it'd be like if their parents weren't their real parents? These stories allow kids to explore the idea, taste the freedom of it, while giving them control to come to their own conclusions about their condition.

The point of this story, succintly expressed in regard to a horse: "People belong to the people who care for them."

The title alludes to the name of a jewel, about which there is some mystery and for which there is a quest of sorts. I'm not convinced it's the most appropriate title for this book, but it does have a marvelously exotic flavour. It hardly matters.

The story was somewhat, but not entirely, predictable — though I doubt it would be tranparent to a 9-year-old — and I kept turning pages regardless. It's so lovingly told.

What I love best is that none of Ibbotson's inhabitants are one-dimensional caricatures of good or evil. They are morally nuanced. Very few decisions are black and white or to be taken lightly. For example, "Disobeying one's mother was difficult... But what if it had to be done?"

One of Annika's friends destroys the music professor's treasured and very expensive harp, for the greater good, of course. I shed a tear when Stefan admits to the deliberateness with which he acted, and Professor Gertrude assures him he did the right thing.

Even our story's villain, acting despicably and valuing the superficial, is shown to be capable of love; the deeds are the result of misplaced priorities and loyalty to tradition.

The language is simple but rich, conveying a different culture and time, while explaining to young readers the nature of spas and Swiss bank accounts.

My hardcover edition has nice black-and-white illustrations by Kevin Hawkes, but, frankly, they do nothing for me — the text paints far richer pictures. I love that a map of central Europe, 1908, sprawls across the inside covers.

The Guardian on Eva Ibbotson, who spent her early years in Vienna and whose parents separated when she was 2, and the experience that informed The Star of Kazan:

School Library Journal Best Book of the Year 2004.

Booklist Editor's Choice 2004.

ALA Notable Book 2005.

This book belongs on every young girl's shelf.

(It came in a box with a large assortment of other literary delights. Embarrassingly large. I ripped through the cardboard, stashed the contents under my side of the bed, and dismantled the box, hurriedly stuffing it and the wrapping material in the recycle bin, which fortunately was already on the curb awaiting pick-up — all traces gone, before J-F returned home from work.)

The Star of Kazan has all the classic elements of a classic children's tale, and then some:

- An orphan foundling

- Eccentric professors

- Horses (Lippizaner, no less)

- Pastries (Viennese, of course)

- Aging chorus girls

- Fabulous jewels

- Castles (dank)

- Gypsies

- Crippled dogs

- Boarding schools (severe and punishing)

Perhaps most importantly, it features a cast of kindly characters with imagination and dreams, and a love and respect for truth and books. And some villains who are pretty nasty. What's not to love!?

This is an adventure showcasing courage in the face of great adversity.

In brief (from School Library Journal):

Abandoned as a baby, Annika is found and adopted by Ellie and Sigrid, cook and housemaid for three professors. Growing up in early-20th-century Vienna, she learns to cook and clean and is perfectly happy until a beautiful aristocrat appears and claims to be her mother, sweeping her off to a new life in a crumbling castle in northern Germany. Annika is determined to make the best of things, and it takes a while for her to realize that her new "family" has many secrets, most of them nasty.

It seems to me that the best children's books feature orphans. At the very least, the parents are out of sight. What child doesn't sometimes wonder what it'd be like if their parents weren't their real parents? These stories allow kids to explore the idea, taste the freedom of it, while giving them control to come to their own conclusions about their condition.

The point of this story, succintly expressed in regard to a horse: "People belong to the people who care for them."

The title alludes to the name of a jewel, about which there is some mystery and for which there is a quest of sorts. I'm not convinced it's the most appropriate title for this book, but it does have a marvelously exotic flavour. It hardly matters.

The story was somewhat, but not entirely, predictable — though I doubt it would be tranparent to a 9-year-old — and I kept turning pages regardless. It's so lovingly told.

What I love best is that none of Ibbotson's inhabitants are one-dimensional caricatures of good or evil. They are morally nuanced. Very few decisions are black and white or to be taken lightly. For example, "Disobeying one's mother was difficult... But what if it had to be done?"

One of Annika's friends destroys the music professor's treasured and very expensive harp, for the greater good, of course. I shed a tear when Stefan admits to the deliberateness with which he acted, and Professor Gertrude assures him he did the right thing.

Even our story's villain, acting despicably and valuing the superficial, is shown to be capable of love; the deeds are the result of misplaced priorities and loyalty to tradition.

The language is simple but rich, conveying a different culture and time, while explaining to young readers the nature of spas and Swiss bank accounts.

My hardcover edition has nice black-and-white illustrations by Kevin Hawkes, but, frankly, they do nothing for me — the text paints far richer pictures. I love that a map of central Europe, 1908, sprawls across the inside covers.

The Guardian on Eva Ibbotson, who spent her early years in Vienna and whose parents separated when she was 2, and the experience that informed The Star of Kazan:

Ibbotson, as loving as she is sharp, lives now surrounded by children and grandchildren but her childhood was a recurring search for mothering.

Her mother went to Paris, while she stayed in Edinburgh with her father - a scientist who pioneered artificial insemination - and a governess. Does she remember what her eight-year-old self felt? "I think I expected things to be chaotic. I was always wanting my mother to come, waiting and rushing out into the street, looking at people with hats like hers. Thirties hat, velour, very sort of clochey.

"She was wonderful when she came. But I think it was just too soon for her to be a mother."

School Library Journal Best Book of the Year 2004.

Booklist Editor's Choice 2004.

ALA Notable Book 2005.

This book belongs on every young girl's shelf.

Wednesday, September 14, 2005

Sky notes

Last month when we arrived at my mother's house, a perfect half moon hung big and low in the sky. That first evening, I pointed it out to Helena in amazement.

She made it our habit, for the duration of our stay, at bedtime to step outside and gaze at the moon. She started singing, "Au claire de la lune...," but neither of us could remember the words. We half hummed, half mumbled; giggled and hugged. It was beautiful.

I called J-F daily to remind me of the lyrics, but they didn't take. It didn't matter.

I've since learned the words and can sing them on demand. Only there's been little need. We've been too busy or too tired to look up. Until we went to the cottage last week.

Since our return, it's been her habit at bedtime to ask Papa to show her the stars. He drops everything at that moment (he wanted be an astronaut). Helena wants a star. They step out into the courtyard.

This evening after supper, Helena and I went for a stroll. The moon was yellow, big and low in the sky. And we sang.

(Even Malaysia goes to the Moon!)

sun moon stars rain

children guessed (but only a few

...)

She made it our habit, for the duration of our stay, at bedtime to step outside and gaze at the moon. She started singing, "Au claire de la lune...," but neither of us could remember the words. We half hummed, half mumbled; giggled and hugged. It was beautiful.

I called J-F daily to remind me of the lyrics, but they didn't take. It didn't matter.

I've since learned the words and can sing them on demand. Only there's been little need. We've been too busy or too tired to look up. Until we went to the cottage last week.

stars rain sun moon

(and only the snow can begin to explain

how children are apt to forget to remember

...)

Since our return, it's been her habit at bedtime to ask Papa to show her the stars. He drops everything at that moment (he wanted be an astronaut). Helena wants a star. They step out into the courtyard.

This evening after supper, Helena and I went for a stroll. The moon was yellow, big and low in the sky. And we sang.

(Even Malaysia goes to the Moon!)

A bunch of junk

(in no way connected, other than giving me way too much to think about, or coherently organized).

Salman Rushdie proposes points for a reform movement of Islam, in which he reminds readers that "the people most directly injured by radical Islam are other Muslims." This after his article in response to the London bombings and the debate it sparked.

Julia Alvarez (whose A Cafecito Story is in my to-read stack) on the challenge of post-9/11 fiction.

The Christian Science Monitor on Jane Smiley's Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel (in which the second half catalogs the 100 books Smiley read for her project, her reasons for choosing them, and her reactions to them).

Slate's second annual Fall Fiction Week.

The relative irrelevance of plot:

Style is not the surface, as might be assumed, but rather . . . it's plot and event that rest lightly on the surface, while style and language do the hard work of plumbing the depths.

Clive Thompson on the video-game novel.

Of course, it's the wrong way 'round. Novels ought to inspire games — the narrative structure, the opportunities for character and plot development and backstory are perhaps even better suited to this medium than to film.

Some years ago I played Timeline. The game was packaged with the paperback, by Michael Crichton, though I assume the book came first. Later there was a film. They were all crap.

Jane Jensen created games that she later developed into novels. I've not read them, but I love her subject material. (Dante's Equation is on the bedside table.)

Books that would make interesting video games? Codex. Perdido Street Station. Maybe Foucault's Pendulum. The Three Musketeers.

The best headline ever, according to Splinters (and I have to agree):

Suicide Grasshoppers Brainwashed by Parasite Worms

Salman Rushdie proposes points for a reform movement of Islam, in which he reminds readers that "the people most directly injured by radical Islam are other Muslims." This after his article in response to the London bombings and the debate it sparked.

Julia Alvarez (whose A Cafecito Story is in my to-read stack) on the challenge of post-9/11 fiction.

Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz once commented that "poetry below a certain awareness is not good poetry . . . that we move, that mankind moves in time together and there is a certain awareness of a particular moment below which we shouldn't go because then that poetry is no good." The same can be said of fiction.

The Christian Science Monitor on Jane Smiley's Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel (in which the second half catalogs the 100 books Smiley read for her project, her reasons for choosing them, and her reactions to them).

Non-English majors read to inform themselves. But English majors read because they like to.

There is a sizable third group that ought to be recognized as well. These could be called the über-English majors: people who, long after school is done, continue to read exactly the same kinds of books required in lit courses. They are often also book club-participants. For them, hurling themselves into weighty books is a pleasure that is most delightful when shared by others.

Slate's second annual Fall Fiction Week.

The relative irrelevance of plot:

Style is not the surface, as might be assumed, but rather . . . it's plot and event that rest lightly on the surface, while style and language do the hard work of plumbing the depths.

Clive Thompson on the video-game novel.

Cross-branding is nothing new, of course, and in the video-game universe it has a long and wretched pedigree, with movie studios producing howlingly awful films like Super Mario Bros. and Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. But even when they sucked, these movies at least seemed like an obvious step, insofar as today's games already closely imitate cinema.

But a novel? When you're in the territory of Jane Austen and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, you're expected to go deeper. You're supposed to probe the internal lives of your characters. And this is where these books become really fascinating: They're like the Us Weekly of the gaming universe.

Of course, it's the wrong way 'round. Novels ought to inspire games — the narrative structure, the opportunities for character and plot development and backstory are perhaps even better suited to this medium than to film.

Some years ago I played Timeline. The game was packaged with the paperback, by Michael Crichton, though I assume the book came first. Later there was a film. They were all crap.

Jane Jensen created games that she later developed into novels. I've not read them, but I love her subject material. (Dante's Equation is on the bedside table.)

Books that would make interesting video games? Codex. Perdido Street Station. Maybe Foucault's Pendulum. The Three Musketeers.

The best headline ever, according to Splinters (and I have to agree):

Suicide Grasshoppers Brainwashed by Parasite Worms

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

Toilet paper notes

This morning, for the first time, of her own accord and because it needed doing, the resident toddler changed the toilet paper roll. Sadly, it appears that she is of the under school.

Monday, September 12, 2005

This is a test

This morning she whined. A lot. A moaning kind of half-cry that tells me she wants something, that not all is to her highness's satisfaction, that her milk isn't warm enough, that her blanket isn't quite right, that she's dropped her stuffed toy and wouldn't deign to pick it up herself, that for my attention to turn to her is taking longer than she'd like.

I wonder sometimes if I spoil her, dote on her. I wonder if others think I do. I'm fairly certain they do.

On the whole, I believe I treat her even-handedly, with love and respect. Her needs are met; her wants are understood and considered, but not always humoured. Not always. Still, I put her before everyone and everything else. And so I should, on the whole. She is, after all, only 2.

Still, when she calls out from another room, I walk away from a conversation. I try to wait for an appropriate pause, but from the moment I hear "Mama," my attention is diverted. When I entertain phonecalls my attention is always divided. It's only polite to at the very least acknowledge her, I think, and we can't expect her to have the patience of an adult.

The whining is unpleasant, a behaviour she's adopted over the last couple months with little sign of abating. It's effective for her — I'm quick to discern and resolve whatever the problem, though increasingly it is a minor disturbance, a mere inconvenience, that sets her vocal chords to work. And still, on the whole, I find myself rationalizing that it's not worth struggling over with her — easier to, say, peel her orange for her, or reach some object or other, than to insist she do it herself, or she wait, and easier by far than to listen to the whining.

I don't believe it's simply to draw and maintain attention on herself. It is, however, manipulative, both a lazy and clever means to a desired end. How much of this is a test? What's the right answer?

This is a test, but this is not a test.

We — she and I — are establishing limits of sorts, learning and settling into our respective roles. He's there too, of course, but, in ways I can't explain, I feel it doesn't concern him. I don't by any means intend to relegate him to a minor role. This particular dramatic tension, one thread among many in the theatre of family life, is somehow personal and private — between her and me. A kind of a power struggle. We need to come an understanding. We are on the brink of a turning point in our character development.

How will her early childhood (in)form her adult attitudes? What kind of person is she going to be?

What kind of mother do I want to be?

We've been establishing a new level of communication. She's told that the whining is not nearly so effective as words. That the whining often impedes communication and delays the desired resolution. That there's no sense in getting worked up about some things. That some things have to wait, and others aren't going to happen. That some things she's perfectly capable of doing for herself. She applies the points of our discussions to subsequent like situations — whatever it was that sparked that particular whining episode. For example, she no longer whines from her bed at night; she clearly states that she'd like some milk or we forgot to leave a light on. But she has yet to generalize — to realize that everything I say applies to all her whining (or rather, that one of those points applies. As I write this I realize perhaps it's too much for me to expect of her, to sift through the options for appropriateness, to know which one applies this time, to foresee the resolution).

This morning she whined a lot. More whining in the bathroom. Was it because I lifted her onto the toilet seat when she'd wanted to wiggle up be herself? Had I pinched her in so doing? Did she want to pull her pants off instead of just down? Had I turned the fan on accidentally (she hates the noise of the fan)? Does she not want to go peepee after all? What? Tell me. Use words. The whining doesn't do anything other than signal your displeasure (and piss me off); the pointing is vague.

The lever for the bathroom sink drain was in the "wrong" position.

This morning I yelled at her. It's not the first time. It won't be the last. It's the worst feeling in the world.

I wonder sometimes if I spoil her, dote on her. I wonder if others think I do. I'm fairly certain they do.

On the whole, I believe I treat her even-handedly, with love and respect. Her needs are met; her wants are understood and considered, but not always humoured. Not always. Still, I put her before everyone and everything else. And so I should, on the whole. She is, after all, only 2.

Still, when she calls out from another room, I walk away from a conversation. I try to wait for an appropriate pause, but from the moment I hear "Mama," my attention is diverted. When I entertain phonecalls my attention is always divided. It's only polite to at the very least acknowledge her, I think, and we can't expect her to have the patience of an adult.

The whining is unpleasant, a behaviour she's adopted over the last couple months with little sign of abating. It's effective for her — I'm quick to discern and resolve whatever the problem, though increasingly it is a minor disturbance, a mere inconvenience, that sets her vocal chords to work. And still, on the whole, I find myself rationalizing that it's not worth struggling over with her — easier to, say, peel her orange for her, or reach some object or other, than to insist she do it herself, or she wait, and easier by far than to listen to the whining.

I don't believe it's simply to draw and maintain attention on herself. It is, however, manipulative, both a lazy and clever means to a desired end. How much of this is a test? What's the right answer?

This is a test, but this is not a test.

We — she and I — are establishing limits of sorts, learning and settling into our respective roles. He's there too, of course, but, in ways I can't explain, I feel it doesn't concern him. I don't by any means intend to relegate him to a minor role. This particular dramatic tension, one thread among many in the theatre of family life, is somehow personal and private — between her and me. A kind of a power struggle. We need to come an understanding. We are on the brink of a turning point in our character development.

How will her early childhood (in)form her adult attitudes? What kind of person is she going to be?

What kind of mother do I want to be?

We've been establishing a new level of communication. She's told that the whining is not nearly so effective as words. That the whining often impedes communication and delays the desired resolution. That there's no sense in getting worked up about some things. That some things have to wait, and others aren't going to happen. That some things she's perfectly capable of doing for herself. She applies the points of our discussions to subsequent like situations — whatever it was that sparked that particular whining episode. For example, she no longer whines from her bed at night; she clearly states that she'd like some milk or we forgot to leave a light on. But she has yet to generalize — to realize that everything I say applies to all her whining (or rather, that one of those points applies. As I write this I realize perhaps it's too much for me to expect of her, to sift through the options for appropriateness, to know which one applies this time, to foresee the resolution).

This morning she whined a lot. More whining in the bathroom. Was it because I lifted her onto the toilet seat when she'd wanted to wiggle up be herself? Had I pinched her in so doing? Did she want to pull her pants off instead of just down? Had I turned the fan on accidentally (she hates the noise of the fan)? Does she not want to go peepee after all? What? Tell me. Use words. The whining doesn't do anything other than signal your displeasure (and piss me off); the pointing is vague.

The lever for the bathroom sink drain was in the "wrong" position.

This morning I yelled at her. It's not the first time. It won't be the last. It's the worst feeling in the world.

Sunday, September 11, 2005

All things China

The final instalment of China Miéville's interview in 3 parts at Long Sunday is finally here (though, honestly, part the first was the most exciting). (Via The Mumpsimus.)

Part 1 (previously mentioned).

Part 2 (which I somehow missed), in which he muses on prose stylings; on political narrative

[...that all political reality will be given a narrative form is inevitable — both on the left and the right. The right, though, pays only the feeblest lip service to making it believable, and instead wants to make it clearly generic not so that consumers will be fooled but so that they will understand the rules. For that purpose, the simpler the pulp form, the better.];

on Palestine; on international law ["The chaotic and bloody world around us IS the rule of law."]; and on his predilection for the Weird.

(Also he notes being pleasantly surprised by the film 'Reign of Fire', — "Post apocalypse. Christian Bale. Dragons. The only film Matthew McConaughey was ever good in. What's not to like?" — although he is mistaken in believing he is the only person in the world to have liked it.)

Part 3, on blogging, on fantasy (and whether the genre has national threads), on magic realism, and a whole lot more on international law.

On world-building and its relation with realism:

On the London bombings at Bionic Octopus.

On Katrina fallout at Lenin's Tomb.

Freshly released short stories: Looking for Jake.

Currently finishing another novel, "licking afterbirth off a kitten."

Part 1 (previously mentioned).

Part 2 (which I somehow missed), in which he muses on prose stylings; on political narrative

[...that all political reality will be given a narrative form is inevitable — both on the left and the right. The right, though, pays only the feeblest lip service to making it believable, and instead wants to make it clearly generic not so that consumers will be fooled but so that they will understand the rules. For that purpose, the simpler the pulp form, the better.];

on Palestine; on international law ["The chaotic and bloody world around us IS the rule of law."]; and on his predilection for the Weird.

(Also he notes being pleasantly surprised by the film 'Reign of Fire', — "Post apocalypse. Christian Bale. Dragons. The only film Matthew McConaughey was ever good in. What's not to like?" — although he is mistaken in believing he is the only person in the world to have liked it.)

Part 3, on blogging, on fantasy (and whether the genre has national threads), on magic realism, and a whole lot more on international law.

On world-building and its relation with realism:

Part of the reason that it is very hard for me to conceive of a truly great Liberal novel for the last few decades is because more or less definitionally they'd be novels that take the world at its own claims. They take it for granted. That I think is partly what Trotsky's after when he says that 'art that loses a sense of the social lie' is what 'becomes mannerism.'...

I think part of the problem with the modern 'liberal' novel is that it often tends not to conceive of the totality of social life: instead it abstracts one element (stereotypically the middle-class family), and universalises it. By contrast, fantastic fiction that 'world-creates' creates a world — a totality. So whether or not it explicitly spells it out, there's a sense that an economic problem conceived of as background and the romantic plot foregrounded are part of the same universe. That's what the classic 19thC realist novel also did. Of course the bad fantasy novel proposes an utterly unconvincing totality, one with elements that we viscerally know to be present, absent.

On the London bombings at Bionic Octopus.

On Katrina fallout at Lenin's Tomb.

Freshly released short stories: Looking for Jake.

Currently finishing another novel, "licking afterbirth off a kitten."

U

Helena hasn't quite got the hang of letter names yet, though she readily associates letters with words they initialize. For example, for "d" she produces "dinosaur," "dragon," "Dora," etc.

This morning, playing with letter magnets:

Me: What's that letter? [I'm pointing at "u," expecting "umbrella."]

Helena: [No response. Looks at me expectantly.]

Me: That's the letter "u."

Helena: Moi? [Her eyes linger on "h," compare with "u," and question me.]

Me: No, "u."

Helena: Toi?

This morning, playing with letter magnets:

Me: What's that letter? [I'm pointing at "u," expecting "umbrella."]

Helena: [No response. Looks at me expectantly.]

Me: That's the letter "u."

Helena: Moi? [Her eyes linger on "h," compare with "u," and question me.]

Me: No, "u."

Helena: Toi?

Saturday, September 10, 2005

Typewriter notes

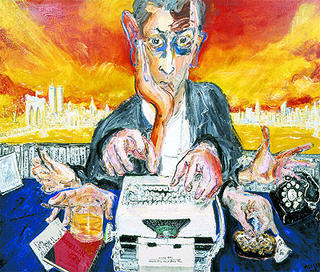

The Story of My Typewriter, by Paul Auster and Sam Messer, is both a love story and a ghost story. Bittersweet because we know eventually the ribbons will run out, the ink will run dry.

This slim volume is disappointing because Auster's spare text is so very short. The relationship between the artist and his machine is complicated, their lives intertwined, yet Auster admits he'd never really given it much thought.

(What does it say about me that I've wanted to fetishize objects — pens, notebooks, and, yes, even typewriters — and these particular objects, instruments of writing, instruments of writers, but I could never really get into it. When I realized, as did Auster, that typewriters were fast becoming dinosaurs, I thought it'd be cool to collect them. I bought a few in junk shops, a couple dollars apiece, thought one would serve nicely as a planter, a couple others as bookends or shelf supports. When I moved to the next apartment, they ended up on the curb. Perhaps because I hadn't actually written anything with these machines. But even if I had? Would I see them as anything other than a tool? I've thrown out pencils, ripped up notebooks that had written or contained some brilliant jottings. None ever became a talisman. I've blogged on more than one keyboard, monitor, computer. I prefer some over others as aesthetic objects, and still others as utilitarian ones, but none has ever evoked object lust.

[The only collection of mine that has taken on a life of its own is the bookmarks. But then, I'm a reader, after all.])

The typewriter, as a thing in itself, if it is a muse or catalyst for anyone, inspires Sam Messer. He paints the Olympia both as a ghostly presence and as a visceral monster.

Most interesting are the paintings depicting Auster and Olympia together, the weird hold they have on each other (the kind of relationship only the outsider can identify), how they intrude on and expand each other.

On Sam Messer (with particular attention to "The Wizard of Brooklyn"):

Exhibition.

I can't help but be reminded of David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch and all it had to say about the creative process (and the utter shit most writers produce).

I can't help but be reminded of David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch and all it had to say about the creative process (and the utter shit most writers produce).

The paintings are brilliantly done, and I am proud of my typewriter for proving itself to be such a worthy subject, but at the same time Messer has forced me to look at my old companion in a new way. I am still in the process of adjustment, but whenever I look at one these paintings now (there are two of them hanging on my living room wall), I have trouble thinking of my typewriter as an it. Slowly but surely, the it has turned into a him.

This slim volume is disappointing because Auster's spare text is so very short. The relationship between the artist and his machine is complicated, their lives intertwined, yet Auster admits he'd never really given it much thought.

(What does it say about me that I've wanted to fetishize objects — pens, notebooks, and, yes, even typewriters — and these particular objects, instruments of writing, instruments of writers, but I could never really get into it. When I realized, as did Auster, that typewriters were fast becoming dinosaurs, I thought it'd be cool to collect them. I bought a few in junk shops, a couple dollars apiece, thought one would serve nicely as a planter, a couple others as bookends or shelf supports. When I moved to the next apartment, they ended up on the curb. Perhaps because I hadn't actually written anything with these machines. But even if I had? Would I see them as anything other than a tool? I've thrown out pencils, ripped up notebooks that had written or contained some brilliant jottings. None ever became a talisman. I've blogged on more than one keyboard, monitor, computer. I prefer some over others as aesthetic objects, and still others as utilitarian ones, but none has ever evoked object lust.

[The only collection of mine that has taken on a life of its own is the bookmarks. But then, I'm a reader, after all.])

The typewriter, as a thing in itself, if it is a muse or catalyst for anyone, inspires Sam Messer. He paints the Olympia both as a ghostly presence and as a visceral monster.

Most interesting are the paintings depicting Auster and Olympia together, the weird hold they have on each other (the kind of relationship only the outsider can identify), how they intrude on and expand each other.

On Sam Messer (with particular attention to "The Wizard of Brooklyn"):

As Messer depicts him, Auster looks like a more robust Kafka — Kafka as a private eye — all dark circles and angst, with a cocked ear the size of a small satellite dish. The head (figuratively speaking) is in one place and the body (which consists of a withered trunk and seven separate hands) in another. One hand, expressionistically elongated, supports his chin, but the others, which are as grasping and acquisitive as claws, lead lives of their own. One stubs out a cigarette while another dials a number on a rotary phone (that other mechanical dinosaur); others type, take notes and smoke; one prepares to lift a glass of whiskey. The page in the typewriter is blank except for the words "The Story of My Typewriter by Paul Auster."

Exhibition.