Flora

I.

One evening last week, Helena announced she didn't want any meat for supper, which was a little odd — the girl loves her red meat. Just broccoli. And, after she scanned the contents of the refrigerator, mango. In no mood to argue, I obliged her. There are worse meals in the world. A whole mango as an appetizer, then three helpings of steamed broccoli. After which, she was pretty set on heading straight to bed. Then she threw up.

The next time Helena wants broccoli and mango for supper, I'll probably think twice before conceding. Probably.

Days later, we're out for a walk and hear sirens. Helena cranes her neck, anticipating a glimpse of a camion pompier. She was a little disappointed to see an ambulance. What's an ambulance? I explain that perhaps there was an accident or someone is very sick and called for help. She runs with the idea: "Peut-etre c'est un monsieur qui a mangé trop du mango."

II.

We did some planting last weekend, which with Helena's help was easily three times the work, time, and mess I'd counted on. We have a nice little container garden now, with a sturdy tomato plant, herbs, and a few flowers.

We've planted some morning glory too. We don't know if it'll thrive in this container environment, but thus far it's been particularly gratifying: opening the packet and counting out the seeds, germinating them in wet paper towel, transferring the seedlings to soil — visible growth, daily, even hourly.

Helena imagines them growing tall, tall, taller than the roof. We must install buttons on them that we can push in order to tell them to stop.

Fauna

(or things Helena cannot believe)

I.

Helena asks what's for supper. Barbecued porkchops, I say. J-F tells her we're having pig. Helena find this to be ridiculous, quite a joke.

Obviously, we've not watched Charlotte's Web often or carefully enough.

II.

There's a mosquito perched on the balcony railing, evidently waiting for the rain to subside. Helena checks on it every few minutes. She asks me where it lives, do I think it's lost, where are its mama and papa. I tell her I don't know. All I know is that when it gets hungry it'll sit on her, poke its "leg" inside her like a needle and drink her blood.

This story yielded wide-eyed amazement, then laughter. Days later Helena has settled into gentle mockery of Mama's crazy story. So crazy, it couldn't possibly be true.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Monday, May 29, 2006

The reading hell into which I descended

So I finally got through the other ingenious and erudite book. I'll give it "erudite." "Ingenious" is perhaps too generous — maybe I'm too stingy? would I call any book ingenious? A blurb from me would say "pretty clever" and "way cool." (But what do I know? Neither do I review books for the New York Times nor am I Doris Lessing — if I met either of these conditions I might be ready and confident to call a work "ingenious.")

The Dante Club, by Matthew Pearl, is what I've been reading the last couple weeks, along with a couple old kids' books I'd dug up. I've been consumed with work — a good thing in the grand scheme of my life, but sheer hell for the now. There is an irony to the fact that the editing project that caused me so much anxiety was in fact about anxiety disorders. One panic attack, another, 782 references to verify, trouble sleeping, yes, I must have panic disorder, I'm sure of it, letting the house go hell in the meantime, no, it's generalized anxiety disorder, job performance anxiety, checking, double-checking, triple-checking, it's obsessive—compulsive (Copyediting! Turn your OCD into a career!), but it's over now, I did a damn good job, and I'm pretty sure any remaining anxiety symptoms I have are subsyndromal.

(This has nothing to do with anything: Did you know only 60% of OCD sufferers are women? That's a significantly lower proportion of women than for any other anxiety disorder. And OCD is the only anxiety disorder for which neurosurgical treatment is actually occasionally considered to be a viable option. Do you think those facts might be connected? A lot of men have OCD, so it must have a biological basis, we can't just keep them drugged up... No, I'm not a psychiatrist or otherwise qualified to draw any conclusions from arbitrarily juxtaposing those two facts. It's just something I noticed and thought odd.)

Oh, right, The Dante Club. In 1865, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was working on a translation of Dante's Divine Comedy and met regularly with Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, and publisher JT Fields to work through some difficulties. This much is historical fact. They grapple with Board politics at Harvard. Meanwhile, some apparently Dante-inspired murders terrorize the city. The victims are sinners representative of those Dante encountered in Hell and are punished accordingly. Boston's brains are on the case. Premise: way cool.

I really hated the first 60 pages. None of the characters were at all differentiated from each other. This muddle was made somewhat muddier by the fact that I know absolutely nothing about Longfellow, Holmes, or Lowell, let alone Dante. But very suddenly, I couldn't put the book down, in part because these characters were finally given back stories and I could finally distinguish between them (a little late perhaps for the average lay reader — I seriously considered giving up on this book, something I never do but am with age considering the merits of), but I think mostly because my work project was wrapping up and I could finally allow myself to give myself over to the story.

The resolution of the murder mystery was somewhat disappointing, but I say that about every single mystery I read, so this criticism of mine really doesn't mean anything. I don't like most endings to most books. Maybe I just don't like them to end. The thrill of the journey and all that.

So, what does this give us? A tedious beginning, a lame ending. And I loved it. Really. Go figure. Plus, I'm dying to check out Dante now.

Excerpt.

Check out the gallery of covers. I have a UK edition (I don't know why) — the flies are in glossy relief on an otherwise smooth matte cover and are realistically unsettling.

In related news, Matthew Pearl has a new book out, The Poe Shadow, featured during Slate's pulp fiction week (the recent boom in historical fiction is briefly discussed). Pearl lists his top 10 books inspired by Poe.

The Dante Club, by Matthew Pearl, is what I've been reading the last couple weeks, along with a couple old kids' books I'd dug up. I've been consumed with work — a good thing in the grand scheme of my life, but sheer hell for the now. There is an irony to the fact that the editing project that caused me so much anxiety was in fact about anxiety disorders. One panic attack, another, 782 references to verify, trouble sleeping, yes, I must have panic disorder, I'm sure of it, letting the house go hell in the meantime, no, it's generalized anxiety disorder, job performance anxiety, checking, double-checking, triple-checking, it's obsessive—compulsive (Copyediting! Turn your OCD into a career!), but it's over now, I did a damn good job, and I'm pretty sure any remaining anxiety symptoms I have are subsyndromal.

(This has nothing to do with anything: Did you know only 60% of OCD sufferers are women? That's a significantly lower proportion of women than for any other anxiety disorder. And OCD is the only anxiety disorder for which neurosurgical treatment is actually occasionally considered to be a viable option. Do you think those facts might be connected? A lot of men have OCD, so it must have a biological basis, we can't just keep them drugged up... No, I'm not a psychiatrist or otherwise qualified to draw any conclusions from arbitrarily juxtaposing those two facts. It's just something I noticed and thought odd.)

Oh, right, The Dante Club. In 1865, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was working on a translation of Dante's Divine Comedy and met regularly with Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, and publisher JT Fields to work through some difficulties. This much is historical fact. They grapple with Board politics at Harvard. Meanwhile, some apparently Dante-inspired murders terrorize the city. The victims are sinners representative of those Dante encountered in Hell and are punished accordingly. Boston's brains are on the case. Premise: way cool.

I really hated the first 60 pages. None of the characters were at all differentiated from each other. This muddle was made somewhat muddier by the fact that I know absolutely nothing about Longfellow, Holmes, or Lowell, let alone Dante. But very suddenly, I couldn't put the book down, in part because these characters were finally given back stories and I could finally distinguish between them (a little late perhaps for the average lay reader — I seriously considered giving up on this book, something I never do but am with age considering the merits of), but I think mostly because my work project was wrapping up and I could finally allow myself to give myself over to the story.

The resolution of the murder mystery was somewhat disappointing, but I say that about every single mystery I read, so this criticism of mine really doesn't mean anything. I don't like most endings to most books. Maybe I just don't like them to end. The thrill of the journey and all that.

So, what does this give us? A tedious beginning, a lame ending. And I loved it. Really. Go figure. Plus, I'm dying to check out Dante now.

Excerpt.

Check out the gallery of covers. I have a UK edition (I don't know why) — the flies are in glossy relief on an otherwise smooth matte cover and are realistically unsettling.

In related news, Matthew Pearl has a new book out, The Poe Shadow, featured during Slate's pulp fiction week (the recent boom in historical fiction is briefly discussed). Pearl lists his top 10 books inspired by Poe.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Wacky Wednesday

One of the very first things I did when Helena was born was sign her up for the Beginning Readers’ Program book club. As a first-time mother who had done absolutely no research about parenting, didn't consort much with other parents, and basically had no idea what she had gotten herself into, it was obvious to me that a steady supply of children's books for the preverbal infant was the utmost priority.

Needless to say, in only a few short months my ideas about parenting were turned upside-down. However, three and a half years later, those few dozen book-club books have found a comfortable place in our lives, though the spines of a couple of them have yet to be cracked.

About once a week (though only rarely on Wednesdays) for the last few months, with a certain mischievous twinkle Helena pulls out Wacky Wednesday, by Theo LeSieg (yes, the good doctor), illustrated by George Booth.

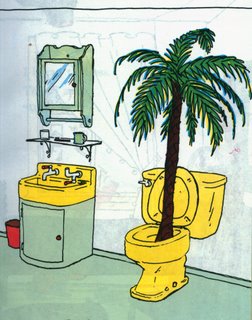

She loves pointing out all the crazy things going on in these pictures — shoes on walls, trees growing out of chimneys, people without heads (she can't yet identify the spelling mistakes in the signage). But this:

— this is the funniest thing Helena has ever seen. This is the page she keeps coming back to. This is the page that prompts hysterical, sometimes maniacal, laughter.

— this is the funniest thing Helena has ever seen. This is the page she keeps coming back to. This is the page that prompts hysterical, sometimes maniacal, laughter.

As we go about our daily business, this is the page that keeps coming to her mind. She'll suddenly remember, "Il y a un arbre dans la toilette." Wait, she says, she'll show me, and she rushes off to retrieve the book. Book in hand, she makes a great show of it, are you ready?, because this is the funniest thing you'll ever see. She laughs and laughs, and I laugh, and eventually we settle into exploring the relative subwackiness of the rest of the book.

Every week. She still thinks it's funny.

Needless to say, in only a few short months my ideas about parenting were turned upside-down. However, three and a half years later, those few dozen book-club books have found a comfortable place in our lives, though the spines of a couple of them have yet to be cracked.

About once a week (though only rarely on Wednesdays) for the last few months, with a certain mischievous twinkle Helena pulls out Wacky Wednesday, by Theo LeSieg (yes, the good doctor), illustrated by George Booth.

She loves pointing out all the crazy things going on in these pictures — shoes on walls, trees growing out of chimneys, people without heads (she can't yet identify the spelling mistakes in the signage). But this:

— this is the funniest thing Helena has ever seen. This is the page she keeps coming back to. This is the page that prompts hysterical, sometimes maniacal, laughter.

— this is the funniest thing Helena has ever seen. This is the page she keeps coming back to. This is the page that prompts hysterical, sometimes maniacal, laughter.As we go about our daily business, this is the page that keeps coming to her mind. She'll suddenly remember, "Il y a un arbre dans la toilette." Wait, she says, she'll show me, and she rushes off to retrieve the book. Book in hand, she makes a great show of it, are you ready?, because this is the funniest thing you'll ever see. She laughs and laughs, and I laugh, and eventually we settle into exploring the relative subwackiness of the rest of the book.

Every week. She still thinks it's funny.

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

Clit lit

The 25 sexiest novels ever written. Some decidedly literary.

What does is say that I've read significantly more of the books on this list than of the best American fiction of the last 25 years?

The sexy list is by far the sexier, not least because it spans many sexy decades (centuries, really) and sexy cultures. (Really, there's not much sexy about either the 80s or America.)

What does it say that Philip Roth is on both lists (although for different titles)?

What does it say that I'd actually be willing to waste time on arguing that Quiet Days in Clichy is by far sexier than Tropic of Cancer?

What does it say that I'm dying to lay my hands on a copy of George Bataille's Story of the Eye?

See also behind the The Story of O:

What's the sexiest novel you've ever read (whatever sexy means to you)?

What does is say that I've read significantly more of the books on this list than of the best American fiction of the last 25 years?

The sexy list is by far the sexier, not least because it spans many sexy decades (centuries, really) and sexy cultures. (Really, there's not much sexy about either the 80s or America.)

What does it say that Philip Roth is on both lists (although for different titles)?

What does it say that I'd actually be willing to waste time on arguing that Quiet Days in Clichy is by far sexier than Tropic of Cancer?

What does it say that I'm dying to lay my hands on a copy of George Bataille's Story of the Eye?

See also behind the The Story of O:

Histoire d'O (Story of O) is an erotic parable about more achieving less. It has far more in common with the travails of medieval saints than with the beleaguered female of modern-day pornography. The book tells the profound, and disturbing, story of a woman who wishes to exist without existing: "She lost herself in a delirious absence from herself."

What's the sexiest novel you've ever read (whatever sexy means to you)?

Saturday, May 20, 2006

Waiting for Beckett

Ian Brown amends his resolution to read the complete works of Samuel Beckett and then write about them, deciding instead to read them all in a single day. "But having done it, I can tell you this: It doesn't make any difference. I imagined Beckett would approve."

By the sounds of it, Brown could've saved himself the better part of a day and spent an hour or so banging his head against the wall to similar effect.

I've never read Beckett apart from that little Godot thing, but this essay makes me want to wallow in the whole mess of it.

By the sounds of it, Brown could've saved himself the better part of a day and spent an hour or so banging his head against the wall to similar effect.

...by the time he gets to The Unnamable, Beckett is content to simply slam your head repeatedly into the thick planks of linguistic hopelessness, proving again and again how meaningless meaning can be.

I've never read Beckett apart from that little Godot thing, but this essay makes me want to wallow in the whole mess of it.

Friday, May 19, 2006

Colouring

This morning when Helena woke me up, I installed her at the kitchen table with crayons and colouring book. I sneaked back to bed to steal a few more minutes' rest, kicking J-F out to take care of child and coffee.

This morning when Helena woke me up, I installed her at the kitchen table with crayons and colouring book. I sneaked back to bed to steal a few more minutes' rest, kicking J-F out to take care of child and coffee.Some minutes later, J-F brought me latte and Helena brought me this picture.

It's the first picture of hers I've seen that looks coloured. That is, somehow ordered, controlled.

Till recently, it seemed our colouring books would just as well have been filled with blank pages. While Helena might take a second to remark on whatever animal or flower was outlined, the crayoning that ensued was a chaotic tangle of colour scribbles with seemingly no correlation to the underlying image. Lately I'd noticed a more careful approach: a proclamation that a particular object should be a certain shade and then a token wisp of wax to make it so.

But this is colouring.

Monday, May 15, 2006

The most beautiful flowers in the world

I never thought Mother's Day was a big deal. I was always extra nice to my mother on that day. We'd prepare a crafty card or some such thing in school, and I remember stealing lilacs off the bush that poked through the fence in a nearby parking lot to give to her all the years we lived in that spot. But I always considered it one of those made-up, commercialized excuses of a holiday, not a cause for real celebration.

Of course, that all changed when I became a mother.

I can't put my finger on it. I'm tempted to say that every day — at least, all those good days, when my girl laughs, when we're in sync, when we're full of love and joy — is Mother's Day. But this weekend was something special.

I was treated to a Saturday without the child, which I spent lazily, puttering and listening to the CBC. (I never thought such a simple pleasure might be thwarted by the presence of a little one, but games, questions, little attentions, and meal preparations are enough to distract me from the point of a story, to miss a punchline. Lazy Saturday mornings is a habit we're only just now being able to slowly, gradually reinstate as she's better able to amuse herself.) We braved torrents of rain to enjoy lunch out. On the drive to retrieve Helena, we hear a recording of an interview with Salman Rushdie, the one I'd ultimately opted not to attend back in the fall but I was glad to hear it now. (I'm unable to find links to audio files or transcripts, though I did find a couple write-ups, one of which I'm certain misquoted Rushdie and neither of which managed to synthesize all the interesting things he had to say. I'm not able to do that either, but he did say wonderfully inspiring things about the purpose of literature to help readers view the world — the real world — a little differently, to incite discussion, to shake things up. It almost makes me want to read The Satanic Verses.)

Sunday was simply lovely, brimming with thoughtful little attentions I won't enumerate here. I did receive as a gift a copy of Stendhal's The Red and the Black, which I'm certain Helena's father had a hand in choosing (if you ask Helena what Mommy's reading, she's still likely to say Don Quixote). (I'm torn whether I want to read it along with a group or savour it all for myself. I cannot explain why I suddenly have so much enthusiasm for this book.)

Et cetera.

Somehow, all weekend, I managed to suppress all work-related stress. Panic erupted this morning and is sure to have a tangible presence all the coming week. I will remind myself to stop and smell the flowers.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

The reading goup project

I've posted a shortlist of possible titles for the next reading group project.

Discussion of Middlemarch is still ongoing. Some are still reading. I for one still have things to say about it (but I've been swamped with work), including my impressions of the 1994 BBC adaptation, which I'm halfway through watching.

But I'd like to start another reading project in a few weeks' time.

The shortlist:

War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ulysses, James Joyce

The Red and the Black, Stendhal

Fathers and Sons, Ivan Turgenev

I'd narrowed it down to the first 4 titles some weeks ago. I added Turgenev only because of the references to it I encountered in Snow.

By coincidence, I was reading an essay, "A book that changed me," by Doris Lessing just this morning:

I'm struck by the overlap in our lists, what it might indicate about where my mind is at.

If you read Middlemarch with us, or if you didn't, and if you want to read one of the above titles, leave a comment at Reading Middlemarch indicating your preference. Reading will likely begin mid-June and carry on through August.

Discussion of Middlemarch is still ongoing. Some are still reading. I for one still have things to say about it (but I've been swamped with work), including my impressions of the 1994 BBC adaptation, which I'm halfway through watching.

But I'd like to start another reading project in a few weeks' time.

The shortlist:

War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ulysses, James Joyce

The Red and the Black, Stendhal

Fathers and Sons, Ivan Turgenev

I'd narrowed it down to the first 4 titles some weeks ago. I added Turgenev only because of the references to it I encountered in Snow.

By coincidence, I was reading an essay, "A book that changed me," by Doris Lessing just this morning:

I do not believe that one can be changed by a book (or by a person) unless there is already something present, latent or in embryo, ready to be changed. Books have influenced me all my life. I could say as an autodidact — a condition that has advantages and disadvantages — that books have made me what I am. But it is hard to say of this book or that one: it changed me. How about War and Peace? Fathers and Sons? The Idiot? The Scarlet and the Black? Remembrance of Things Past? But now they all seem dazzling stages in a long voyage of discovery, which continues.

I'm struck by the overlap in our lists, what it might indicate about where my mind is at.

If you read Middlemarch with us, or if you didn't, and if you want to read one of the above titles, leave a comment at Reading Middlemarch indicating your preference. Reading will likely begin mid-June and carry on through August.

A complication, of sorts

As it turns out, The Grand Complication, by Allen Kurzweil, is neither ingenious nor particularly erudite, as Doris Lessing claimed it to be, and for this, Lessing has fallen a little in my estimation, though I console myself a little, thinking that were I to confront her on this shameless blurbing, she'd wave it off, "Business, you know, and besides, that was years ago; maybe I exaggerated, but still, it was quite fun."

I shouldn't gripe. I hadn't wanted ingenious or erudite; I'd wanted something light, and that's what I got. A nice little diversion, about library cataloguing and research.

(I'd enjoyed A Case of Curiosities a couple years ago.)

The resolution is clumsy, the villain's motivations never made clear (I love a bit of ambiguity, but this just lacked sense), the love story not quite credible. There are some annoying shifts in tone, for which I'm sure I could muster up a logical rationale if I set my mind to it, but I can't be bothered.

The Literary Saloon has a review, along with a comprehensive list of others.

It's a little bit clever, but there's really not much else to it. Which is fine.

I shouldn't gripe. I hadn't wanted ingenious or erudite; I'd wanted something light, and that's what I got. A nice little diversion, about library cataloguing and research.

(I'd enjoyed A Case of Curiosities a couple years ago.)

The resolution is clumsy, the villain's motivations never made clear (I love a bit of ambiguity, but this just lacked sense), the love story not quite credible. There are some annoying shifts in tone, for which I'm sure I could muster up a logical rationale if I set my mind to it, but I can't be bothered.

The Literary Saloon has a review, along with a comprehensive list of others.

It's a little bit clever, but there's really not much else to it. Which is fine.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

Literary "gentlemen"

A while ago (Is it already a month? Ack!) I attended a reading as part of Montreal's Blue Metropolis Literary Festival. The event was to feature 3 "literary gentlemen."

As should be obvious from the amount of time I allowed to lapse before filing this report, I felt no pressing need to tell the world about what I'd seen and heard. Still, it was nice to get out.

Tim Parks

I wondered why the name was so familiar. Of course, I'd seen the name splashed across his novels but was never tempted to pick one up. It turns out that I know his name because he has translated the work of Italo Calvino.

Tim Parks is an odd little man. He seemed friendly enough, cracking jokes about the coffee and chocolates some of the audience carried in with them. After about 50 of us have taken our places, he is introduced. In response to the host's remarks, he mutters audibly and with a wink that there's "no such thing as an important literary prize."

He chats briefly about the book tour circuit (something to the effect of: People read! They come to these things!), and manages to disparage the quality of Harry Potter and The DaVinci Code while implying he is more worthy of their rankings.

Parks will read from Rapids. He provides some context, warns about the use of kayaking terminology, for example "stopper" — "not a word you're familiar with, but we'll see." He reads from a paperback, well-worn and dog-eared. I can see he has marked passages, scribbled notes in the margins.

He's nervous. His eyes dart. His hands are shaking. I'm sitting quite close and am distracted by the rustling of the cloth over the authors' table; I realize he's kicking.

The reading is animated, expressive. He does voices, accents. The story is boring.

There's time for only 2 questions: One had something to do with age or experience and elucidated the audience as to how the questioner spent his morning and his delayed reaction to an art exhibition he saw last week. The other question, posed by the moderator, pointed out that Tim Parks, living in Italy, is essentially cut off from the evolving Enlgish language. He responds vaguely but wisely that when you know something is going to be one way, you'd better decided early on it was an advantage.

Later, as I'm leaving, I overhear someone asking Parks about translating Calvino. Parks seems modest, clarifies that he's only translated a couple works (interestingly, I find these to be among the very least engrossing of Calvino's oeuvre); then, looking over his shoulder as if to ensure he's overheard by only the right people, "Most of them are translated by William Weaver, and not very well."

Gentleman? Not so much.

José Carlos Somoza

Somoza looks serious and suspicious. There's no doubt he is taking in everything.

This is only the second time, he says, that he's given a reading in English. He mispronounces (for example, "you-nexpected" for "unexpected" — quite charming really after the initial moment of deciphering), stammers and repeats, but he is very composed. The story speaks for itself.

From the book jacket of The Art of Murder:

Excerpt.

Somoza pauses to give us some context for the various snippets he reads. He clarifies that artists work not only on the canvas bodies, but on their minds, to prepare them to be art.

It's worth noting that Somoza gave up a career in psychiatry to pursue writing. His training is put to obvious use in developing symbols, themes, character psychologies — attics hold the secrets of childhood, the attraction of the forbidden. Some of the writing comes off as cliché, but it's gripping nonetheless.

I will be reading this novel.

Gentleman? I think yes.

David Bezmozgis

The reason for which I purchased a ticket. Cancelled. His father ill.

Perhaps he's too young to be seriously considered a gentleman. His writing: decidedly ungentlemanly, if at times gentle.

Ironically, Bezmozgis's casual style, his material, family stories, short stories — the idea of his writing — appeals to me least (compared with the other authors at this event). But his book was undeniably touching and entertaining, and it's what drew me there. Parks is the self-proclaimed literary one, boring in his book and a bit of an asshole in person. Somoza strikes me as a happy medium, his novel like literary pulp (maybe a little like Arturo Perez-Reverte), and I'm glad to have discovered him.

(More readings should be multiauthor events! How better to be introduced to work that is vaguely similar to that by an admired author but new!)

Bonus gentleman: José Saramago

No, I did not see him that weekend. However, while wondering around the festival venue and perusing various flyers it came to my attention that, at long last, the transcript of his conversation with Adrienne Clarkson, to which I was witness last summer in Ottawa, is allegedly now available in English (though I am unable to find it among the archives).

His latest novel, Seeing, is recently released. (No, I haven't read it yet.)

Ursula K LeGuin: "It's hard not to gallop through prose that uses commas instead of full stops, but once I learned to slow down, the rewards piled up: his sound, sweet humour, his startling imagination, his admirable dogs and lovers, the subtle, honest workings of his mind. Here indeed was a novelist worthy of a reader's trust."

As should be obvious from the amount of time I allowed to lapse before filing this report, I felt no pressing need to tell the world about what I'd seen and heard. Still, it was nice to get out.

Tim Parks

I wondered why the name was so familiar. Of course, I'd seen the name splashed across his novels but was never tempted to pick one up. It turns out that I know his name because he has translated the work of Italo Calvino.

Tim Parks is an odd little man. He seemed friendly enough, cracking jokes about the coffee and chocolates some of the audience carried in with them. After about 50 of us have taken our places, he is introduced. In response to the host's remarks, he mutters audibly and with a wink that there's "no such thing as an important literary prize."

He chats briefly about the book tour circuit (something to the effect of: People read! They come to these things!), and manages to disparage the quality of Harry Potter and The DaVinci Code while implying he is more worthy of their rankings.

Parks will read from Rapids. He provides some context, warns about the use of kayaking terminology, for example "stopper" — "not a word you're familiar with, but we'll see." He reads from a paperback, well-worn and dog-eared. I can see he has marked passages, scribbled notes in the margins.

He's nervous. His eyes dart. His hands are shaking. I'm sitting quite close and am distracted by the rustling of the cloth over the authors' table; I realize he's kicking.

The reading is animated, expressive. He does voices, accents. The story is boring.

There's time for only 2 questions: One had something to do with age or experience and elucidated the audience as to how the questioner spent his morning and his delayed reaction to an art exhibition he saw last week. The other question, posed by the moderator, pointed out that Tim Parks, living in Italy, is essentially cut off from the evolving Enlgish language. He responds vaguely but wisely that when you know something is going to be one way, you'd better decided early on it was an advantage.

Later, as I'm leaving, I overhear someone asking Parks about translating Calvino. Parks seems modest, clarifies that he's only translated a couple works (interestingly, I find these to be among the very least engrossing of Calvino's oeuvre); then, looking over his shoulder as if to ensure he's overheard by only the right people, "Most of them are translated by William Weaver, and not very well."

Gentleman? Not so much.

José Carlos Somoza

Somoza looks serious and suspicious. There's no doubt he is taking in everything.

This is only the second time, he says, that he's given a reading in English. He mispronounces (for example, "you-nexpected" for "unexpected" — quite charming really after the initial moment of deciphering), stammers and repeats, but he is very composed. The story speaks for itself.

From the book jacket of The Art of Murder:

In 2006, the art world has moved far beyond sheep in formaldehyde and the most avant-garde movement is to use living people as artwork. Undergoing weeks of preparation to become 'canvases', the models are required to stay in their pose for ten to twelve hours a day and, as art pieces, they are also for sale. After being exhibited, the 'canvases' can be bought and taken to the purchaser's home, where they are rented for weeks or months.

Many beautiful young men and women long to become a 'canvas' — knowing they are a masterpiece and worth millions seems to make all the sacrifices worthwhile...

Excerpt.

Somoza pauses to give us some context for the various snippets he reads. He clarifies that artists work not only on the canvas bodies, but on their minds, to prepare them to be art.

It's worth noting that Somoza gave up a career in psychiatry to pursue writing. His training is put to obvious use in developing symbols, themes, character psychologies — attics hold the secrets of childhood, the attraction of the forbidden. Some of the writing comes off as cliché, but it's gripping nonetheless.

I will be reading this novel.

Gentleman? I think yes.

David Bezmozgis

The reason for which I purchased a ticket. Cancelled. His father ill.

Perhaps he's too young to be seriously considered a gentleman. His writing: decidedly ungentlemanly, if at times gentle.

Ironically, Bezmozgis's casual style, his material, family stories, short stories — the idea of his writing — appeals to me least (compared with the other authors at this event). But his book was undeniably touching and entertaining, and it's what drew me there. Parks is the self-proclaimed literary one, boring in his book and a bit of an asshole in person. Somoza strikes me as a happy medium, his novel like literary pulp (maybe a little like Arturo Perez-Reverte), and I'm glad to have discovered him.

(More readings should be multiauthor events! How better to be introduced to work that is vaguely similar to that by an admired author but new!)

Bonus gentleman: José Saramago

No, I did not see him that weekend. However, while wondering around the festival venue and perusing various flyers it came to my attention that, at long last, the transcript of his conversation with Adrienne Clarkson, to which I was witness last summer in Ottawa, is allegedly now available in English (though I am unable to find it among the archives).

His latest novel, Seeing, is recently released. (No, I haven't read it yet.)

Ursula K LeGuin: "It's hard not to gallop through prose that uses commas instead of full stops, but once I learned to slow down, the rewards piled up: his sound, sweet humour, his startling imagination, his admirable dogs and lovers, the subtle, honest workings of his mind. Here indeed was a novelist worthy of a reader's trust."

Monday, May 08, 2006

On my television

Edward R Murrow, speech to the Radio-Television News Directors Association, 1958:

Forty-eight years later...

Good night, and good luck.

Our history will be what we make it. And if there are any historians about fifty or a hundred years from now, and there should be preserved the kinescopes for one week of all three networks, they will there find recorded in black and white, or color, evidence of decadence, escapism and insulation from the realities of the world in which we live.

*****

This instrument can teach, it can illuminate; yes, and it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise it is merely wires and lights in a box. There is a great and perhaps decisive battle to be fought against ignorance, intolerance and indifference.

Forty-eight years later...

Good night, and good luck.

Friday, May 05, 2006

The new Number 6

This news is the most exciting thing I've had to be excited about in a long time! Kind of like the excitement of last year's Dr Who revival and the excitement of getting The Prisoner DVD boxset for my birthday a couple years ago combined!

(Thanks for the news, Ed!)

(Oh, I'm so excited!)

(Thanks for the news, Ed!)

(Oh, I'm so excited!)

It's a girl!

I remember the horrid experience of the ultrasound. I was overwhelmed, scared, tense. Alone (J-F couldn't make the appointment), in an unfamiliar setting (having just moved to a new city), grappling poorly in a second language for any hope of communication with the staff, waiting with an overfull bladder, and generally worried, confused, emotional. Everything was OK, normal, no reason not to be, just fine; but a little voice niggled: Are you sure? How can they be sure? I won't let my guard down. I have every reason to be concerned, tense.

I remember the horrid experience of the ultrasound. I was overwhelmed, scared, tense. Alone (J-F couldn't make the appointment), in an unfamiliar setting (having just moved to a new city), grappling poorly in a second language for any hope of communication with the staff, waiting with an overfull bladder, and generally worried, confused, emotional. Everything was OK, normal, no reason not to be, just fine; but a little voice niggled: Are you sure? How can they be sure? I won't let my guard down. I have every reason to be concerned, tense.Then she told me, It's a girl, and for the first time in days, I smiled. That smile imprinted itself on my heart, I think — my heart melted a little and I could no longer control the muscles in my face.

Of course, I'm pretty sure I'd've had the exact same reaction if she'd told me I was having a boy. Pretty sure.

I'd never envisioned a baby girl in pink or daydreamed about doing mother–daughter stuff. But then I'd never been dreamy-eyed over motherhood at all or had any vision of that future except as a vague, blurry Someday. I was relieved to have a girl, because I know nothing about boys. But it turns out it's not so simple.

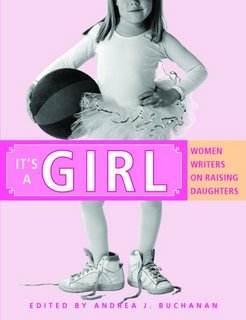

It's a Girl: Women Writers on Raising Daughters is the latest anthology edited by Andrea J Buchanan. As it's so succintly and accurately stated at Parent Hacks, "Andi's books are a central part of the growing conversation (in print and online) about the realities of middle-class, American motherhood." (The review there has sparked a great discussion on gender identity.)

Read the Introduction.

Mothering a girl, according to these writers, makes a woman face herself anew, reliving her own experiences growing up as a girl. The mother of a girl must plumb the depths of the girlhood she'd thought she had safely escaped — but this time through the eyes of her daughter, whose experience is necessarily different. The pain and joy of this reliving, the merging of mother and daughter experience, and the bittersweet, inevitable separation between the two, is at the core of mothering a girl — and at the heart of the essays that make up this book.

That's it, really. This collection is less about daughters than it is about mothers coming to terms with themselves, their own sense of girlness and womanhood, the awareness of how that sense grew out their relationships with their mothers. Emulate our mothers, or distance ourselves from their legacy?

I'm sure many readers will find it reassuring, but I find it troubling that so many (were there really that many, or did my reaction to them exaggerate their number in my mind?) of these essays centred on body-image. (Maybe I'm too much in denial, my vehemence in eschewing the latest fashion trends and resistance to dieting betrays an overcompensation, an armour of words I've built up around a less-than-perfect body.) I'd hoped we were past that.

No essay reflects my experience closely, but every one of them has a little something I relate to.

See Mothershock this week for Andi's take on specific essays.

Follow the blog book tour:

Arch Words

Left-handed Trees and Other Lies: Keeping It All Honest

Mom Brain

The Mommy Blog

Mommy Needs Coffee

Mom Writes

MUBAR

Parent Hacks

Phantom Scribbler

Scribbling Woman

Wet Feet

Woulda Coulda Shoulda

Related books also edited by Andi:

Literary Mama: Reading for the Maternally Inclined, my review of.

It's A Boy: Women Writers on Raising Sons, a few words about.

When I first wrote to Andi to express my interest in It's A Girl, I mentioned some of the issues I'd been grappling with.

The way J-F rolls his eyes and mutters "Women..." when Helena has a tantrum. Even little girls are emotionally complex, he says. When a boy has a tantrum you know exactly why. Is it because I'm female that I'm quicker to figure her tantrums out, because I'm her mother, because I spend more time with her — which of these is behind my knowing her better? Is it true that boys are simpler, easier?

His surprise at my sister's choice of a trainset as a birthday gift for a little girl.

That Helena for a while seemed to be far more girly than I thought possible as the daughter of someone who's never cared for clothes, makeup, etc. Where does she get it from? And what do I do about it (nurture, suppress, ignore)? (The girliness has waned somewhat in recent months, or maybe I don't notice anymore.)

As a counterbalance to the girliness, Helena's bossy and even bully-ish, decidedly "unfeminine," in her daycare group (she's physically larger than most of them).

Just yesterday Helena asked for a new toothbrush, her Winnie-the-Pooh brush at daycare is getting old. She wants a Power Rangers toothbrush, or maybe Batman. J-F is uncomfortable with the un-girliness of it all, and I'm uncomfortable with the fact that he's uncomfortable about it.

How much control do I really have over any of this? Does any of it matter?

The essays in It's A Girl don't have any answers. But they're honest about it.

Pamuk, PEN World Voices

Orhan Pamuk on April 25 delivered the inaugural Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Memorial Lecture at the PEN World Voices festival:

I don't know that it's a peculiarly modern condition, but it's one Pamuk explores superbly in Snow.

I always have difficulty expressing my political judgments in a clear, emphatic, and strong way — I feel pretentious, as if I'm saying things that are not quite true. This is because I know I cannot reduce my thoughts about life to the music of a single voice and a single point of view — I am, after all, a novelist, the kind of novelist who makes it his business to identify with all of his characters, especially the bad ones. Living as I do in a world where, in a very short time, someone who has been a victim of tyranny and oppression can suddenly become one of the oppressors, I know also that holding strong beliefs about the nature of things and people is itself a difficult enterprise. I do also believe that most of us entertain these contradictory thoughts simultaneously, in a spirit of good will and with the best of intentions. The pleasure of writing novels comes from exploring this peculiarly modern condition whereby people are forever contradicting their own minds. It is because our modern minds are so slippery that freedom of expression becomes so important: we need it to understand ourselves, our shady, contradictory, inner thoughts, and the pride and shame that I mentioned earlier.

I don't know that it's a peculiarly modern condition, but it's one Pamuk explores superbly in Snow.

Thursday, May 04, 2006

Choosing a book

Trying to decide what to read next.

I want something light, something without politics. I read a chapter of China Miéville's Iron Council and decide the language is too rich for me to digest right now, and it is far too political, even if this revolution brews in a wholly imagined world.

I go through the stack (there's another stack downstairs, but that's far too far away to be relevant) and methodically eliminate the possiblities. I'm left with two books for closer inspection and begin to compare blurbs.

One book:

"Ingenious... Sparkling with erudition."

The other book:

"I admire this ingenious, erudite book."

What kind of choice is that? Who wants erudition?

I want something light, something without politics. I read a chapter of China Miéville's Iron Council and decide the language is too rich for me to digest right now, and it is far too political, even if this revolution brews in a wholly imagined world.

I go through the stack (there's another stack downstairs, but that's far too far away to be relevant) and methodically eliminate the possiblities. I'm left with two books for closer inspection and begin to compare blurbs.

One book:

"Ingenious... Sparkling with erudition."

The other book:

"I admire this ingenious, erudite book."

What kind of choice is that? Who wants erudition?

Snow

Snow, by Orhan Pamuk, is wonderfully evocative and extremely complex.

Snow is the most recent selection of the Reading Matters book group. I'd previously read Pamuk's My Name is Red (set in 16th-century Istanbul) — I particularly enjoyed the philosophical discussion of the nature of art and how Eastern and Western attitudes toward art differ, although the novel's structure felt contrived. Snow, set in modern times, touches on similar themes but goes well beyond them, to touch on pretty much everything.

Snow is quite obviously the prevailing motif of Snow. It works to isolate the city of Kars (roads are closed), while something dark metaphorically falls over it. Snow makes it picturesque, temporarily obliterating its squalor (which makes itself felt otherwise). Our hero in snow recaptures childhood, innocence, God, peace. Snow's crystalline structure is the inspiration for a series of poems Ka writes; the novel has its own geometry. While the snow falls Kars is suspended from reality; the first half of the novel itself freezes time, relating events that occur over about a day. Then the thaw, the ugliness, the hidden workings; time becomes fluid again.

Excerpt.

For a plot summary, see the reviews:

Margaret Atwood's review.

(Some comments on that review.)

The Literary Saloon has its own review along with a comprehensive list of others.

For my thoughts on more specific aspects of the book, see Reading Matters.

I particularly like the characterizations of Snow's minor players. They're complicated products of circumstance and ideals, sometimes weird, riddled with contradictions and failures, larger than life, but all still sympathetic and believable.

Turgenev's Father and Sons is mentioned a few times in Snow. I think I actually read it for school but remember nothing of it. I suspect these two novels have a closer relationship than anyone has yet discussed: the struggle with tradition and national identity, revolution in the air.

See also:

Discussion at Bookninja Magazine.

The NY Times Reading Group discussion includes some informative points (and links to other sources) on the following:

-Turkish history, Turkey's relationship to Europe and specifically Germany.

-The issue of headscarves, both in relation to Turkey and to Islam.

-The metafictional aspects of the novel, how the narrator's intrusion works to complement the tensions of the novel and underscore the theme of the significance, impact, and place of art.

What all these reviews and discussions highlight for me is just how big Snow is. While they raise fascinating points on Turkish history, Islam, religious state vs secularism, tradition vs modernity, East vs West, the nature art, art & politics, women in Islam, women vs men (in how both events and emotions are processed), love, God, betrayal, revolution, national identity, memory, failure, shame, metafiction, and purity, I still come away with the feeling the surface of this novel has been barely scratched.

Snow is the most recent selection of the Reading Matters book group. I'd previously read Pamuk's My Name is Red (set in 16th-century Istanbul) — I particularly enjoyed the philosophical discussion of the nature of art and how Eastern and Western attitudes toward art differ, although the novel's structure felt contrived. Snow, set in modern times, touches on similar themes but goes well beyond them, to touch on pretty much everything.

Snow is quite obviously the prevailing motif of Snow. It works to isolate the city of Kars (roads are closed), while something dark metaphorically falls over it. Snow makes it picturesque, temporarily obliterating its squalor (which makes itself felt otherwise). Our hero in snow recaptures childhood, innocence, God, peace. Snow's crystalline structure is the inspiration for a series of poems Ka writes; the novel has its own geometry. While the snow falls Kars is suspended from reality; the first half of the novel itself freezes time, relating events that occur over about a day. Then the thaw, the ugliness, the hidden workings; time becomes fluid again.

Excerpt.

For a plot summary, see the reviews:

Margaret Atwood's review.

(Some comments on that review.)

The Literary Saloon has its own review along with a comprehensive list of others.

For my thoughts on more specific aspects of the book, see Reading Matters.

I particularly like the characterizations of Snow's minor players. They're complicated products of circumstance and ideals, sometimes weird, riddled with contradictions and failures, larger than life, but all still sympathetic and believable.

Turgenev's Father and Sons is mentioned a few times in Snow. I think I actually read it for school but remember nothing of it. I suspect these two novels have a closer relationship than anyone has yet discussed: the struggle with tradition and national identity, revolution in the air.

See also:

Discussion at Bookninja Magazine.

The NY Times Reading Group discussion includes some informative points (and links to other sources) on the following:

-Turkish history, Turkey's relationship to Europe and specifically Germany.

-The issue of headscarves, both in relation to Turkey and to Islam.

-The metafictional aspects of the novel, how the narrator's intrusion works to complement the tensions of the novel and underscore the theme of the significance, impact, and place of art.

What all these reviews and discussions highlight for me is just how big Snow is. While they raise fascinating points on Turkish history, Islam, religious state vs secularism, tradition vs modernity, East vs West, the nature art, art & politics, women in Islam, women vs men (in how both events and emotions are processed), love, God, betrayal, revolution, national identity, memory, failure, shame, metafiction, and purity, I still come away with the feeling the surface of this novel has been barely scratched.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

What I've been up to

My eyeballs!

In tax crap. The paperwork is mostly over now, with some more organizing and filing away still to do. I don't even mind the number-crunching and paperwork so much. It's the stinging slap of reality that lingers and weighs on me. Sigh.

In work. A new project I desperately want to not fuck up. Must not procrastinate. Must discipline myself.

In rain. I love rain. But I could do without the fuzzy sinuses and migraines.

In Snow. Discussion ongoing, if lacking in participants. Read it! It's... important. Somehow.

In the sunshine of my life:

I have the distinct impression Helena is practicing her English. Since she started daycare, she's favoured speaking French. I've asked her about this in the past and she's shrugged her shoulders — I speak to her primarily in English, there's no doubt she understands everything I say, and her exposure to books and television is also generally via English; but French is easier for her, it's the language of her daily activities and her peers. From Dora she hears Spanish. From my mother, Polish. We also have books in Polish, songs, and I sprinkle phrases here and there. Suddenly this weekend, she is aware of different languages. After one motherly admonition in Polish slips out, she asks, "Pourquoi tu parles comme Babcia?" She knows there are multilingual seeds planted in her. For now, she practices English, looking to me for confirmation, even asking me about particular words.

We took Helena for a haircut on the weekend. While awaiting our turn, we stop into the pet store next door. The resident big blue parrot says "buh-bye" while lifting one foot and flexing his talons in a makeshift wave. Helena hasn't stopped talking about this amazing bird.

In tax crap. The paperwork is mostly over now, with some more organizing and filing away still to do. I don't even mind the number-crunching and paperwork so much. It's the stinging slap of reality that lingers and weighs on me. Sigh.

In work. A new project I desperately want to not fuck up. Must not procrastinate. Must discipline myself.

In rain. I love rain. But I could do without the fuzzy sinuses and migraines.

In Snow. Discussion ongoing, if lacking in participants. Read it! It's... important. Somehow.

In the sunshine of my life:

I have the distinct impression Helena is practicing her English. Since she started daycare, she's favoured speaking French. I've asked her about this in the past and she's shrugged her shoulders — I speak to her primarily in English, there's no doubt she understands everything I say, and her exposure to books and television is also generally via English; but French is easier for her, it's the language of her daily activities and her peers. From Dora she hears Spanish. From my mother, Polish. We also have books in Polish, songs, and I sprinkle phrases here and there. Suddenly this weekend, she is aware of different languages. After one motherly admonition in Polish slips out, she asks, "Pourquoi tu parles comme Babcia?" She knows there are multilingual seeds planted in her. For now, she practices English, looking to me for confirmation, even asking me about particular words.

We took Helena for a haircut on the weekend. While awaiting our turn, we stop into the pet store next door. The resident big blue parrot says "buh-bye" while lifting one foot and flexing his talons in a makeshift wave. Helena hasn't stopped talking about this amazing bird.

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Family portrait

That's me in red. Helena's green. The yellow is sometimes the cat (who is in real life black as night), but usually the light is such that it's not visible at all. The blue folk keep changing identities, but include J-F, all the grandparents, and others.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)