We start the book believing the eponymous Chilean poet is Gonzalo, but later realize it could instead be Carla's son, Vicente. Or perhaps it is neither of them specifically, but rather a breed of poet, like the domestic shorthair, and the novel a study of the creature's history and environment, influences and influence.Whenever dawn caught him in motion, Gonzalo tended to feel like there was some kind of link between the birth of the light and the very fact of moving forward, as if the walker were somehow responsible for the dawn, or the other way around: as if the dawn generated the movement of feet over sidewalk. He was about to say this to Carla, but he wasn't sure he could explain it, he was afraid of getting tangled up, and he felt like anything he said could spoil that beautiful senseless morning.

(Why is there a cat on the cover anyway? Pru wants to write about the stray dogs Chile is overrun by, like the poets are dogs, and she is led by them, or maybe in fact poets are the opposite of dogs — tolerated, cared for, nurtured, loved. The cover illustration is credited to Laura Wächter and titled "Darkness," so it is clearly a portrait of the family pet, who did play a pivotal but not central role in the novel, so unless he's a poet, it's a surprising choice to feature him on the cover.)

I was prepared to dislike Chilean Poet, by Alejandro Zambra, because it might not live up to Multiple Choice, or it would show it up for the gimmick it was and prove Zambra incapable of depth beyond gimmickry. Also, the opening pages felt very male, as if they could not have been written by anyone who hadn't been a teenage boy, and I thought, this may not be something I want to read right now.

But it's charming, that boy somehow charmed me, maybe the fact that he wanted to be a poet gave his character a layer of complexity, took the edge off the masculinity.

Usually Carla wanted to be where she was and who she was.

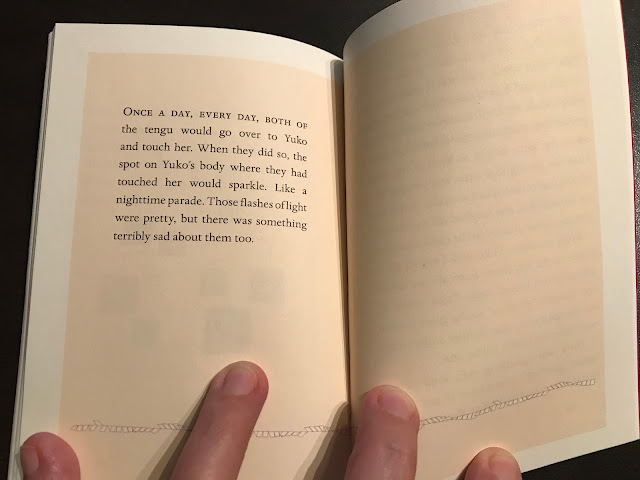

People say that's what happiness is — when you don't feel like you should be somewhere else, or someone else. A different person. Someone younger, older. Someone better.

It's a perfect and impossible idea, but still, during all those years, Carla generally wanted to be exactly were she was.

Chilean Poet is a love story, or two, or more. As an intergenerational drama, everyone's driven by different values, but they all simply want to get the most out of life. This novel is also a crash course in the country's literary tradition and the politics that accompany it.

"It's better to write than not to write. Poetry is subversive because it exposes you, tears you apart. You dare to distrust yourself. You dare to disobey. That's the idea, to disobey everyone. Disobey yourself, that's the most important thing. That's crucial. I don't know if I like my poems, but I know that if I hadn't written them I'd be dumber, more useless, more individualistic. I publish them because they're alive. I don't know if they're good, but they deserve to live."

"A lot of people say that poetry is useless."

"They're afraid of useless things. Everything has to have purpose. They hate pure creation, they're in love with corporations. They're afraid of solitude. They don't know how to be alone."

LitHub: Excerpt

Atlantic: A Fascinating Portrait of a Country at a Turning Point