But how does a person learn to see herself as nothing when she has already had so much trouble learning to see herself as something in the first place? [...] You have been a negative nothing, now you want to be a positive nothing.

— from "New Year's Resolution," in The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, by Lydia Davis.

He asks me about my summer, have I taken vacation. I mumble noncommittally.

I feel the nitrile graze my lip as he positions his fingers inside my mouth. My lip reacts and I suppress my lip from reacting, it is like being touched without being touched, there is no tenderness but it is a gentle sensation.

I tell myself to relax the muscles of my face, around the corners of my mouth, and at my left temple. I wonder how good he is at reading faces. Can he read trepidation? Does he see pain? Has he learned to ignore it? Does he respond to it, does it influence his examination? Maybe he leans into it, tries to extrude it like a fleck of debris with his scaler.I feel a twinge deep in the gum above an upper canine, I think I am reflexively wincing, I tell myself not to wince, I don't actually feel pain, I don't want him to see pain, there is no pain. It tickles a little.

The motor doesn't sound so loud, like I'm hearing everything through a woolen sock, only the sock is lining the inside of my head.

I think about how like it is to the rotary tool I have to sand and finish my sculptures. He is polishing the enamel, and I am like stone, stone flesh with detached nerves, a soft core deep inside wondering how much can the body bear, when will the outer shell crack. But the vibrations are almost delicate — am I so inured, or so removed?

*****

I receive in my inbox an excerpt from "Night Bakery" by Fabio Morábito. It begins thusly:

During my time in Berlin I just walked around and didn’t read a single book. In a way I replaced reading with walking.

I think about this for days, while walking cross my new neighbourhood. It's not mine yet, I haven't fully inhabited it. This is a temporary state. I am hovering above the world, above life, before alighting.

I think about all the nonreading and nonwriting, and this unsatisfying nonwalking, the wondering without concluding. I decide to order this book of stories — it takes what feels like hours to find this line again, to find the newsletter, to trace it to its source, to pinpoint the thing that is affecting me — but am dismayed to learn it will not be published till next spring. Time enough for me to write my own stories. I think all fiction is speculation.

I stumble across a list that looks like the bibliography of my writing project of the last two years. "The books in this list explore, inhabit, and investigate physical hunger." Is it physical?

*****

One day I need to run an errand in the old neighbourhood. I have coffee before setting out, and browse headlines on my phone. I realize the NYRB fiction issue is out, and I think I should pick up a copy. (I want to be the kind of person who picks up the fiction issue. Do I want to be seen or known as the kind of person who picks up the fiction issue? I believe the being seen and being known are not important to me, it's the being that's important, but I can't be sure.)

My errand becomes two errands. The original errand is crucial and time-sensitive, other people rely on its completion for their comfort and well-being, but the new errand born of impulse and frivolity becomes the day's focus.

I finally find a copy and am relieved that it feels right and familiar. This is the kind of person I am. (I know these books reviewed by authors of other books I know.)

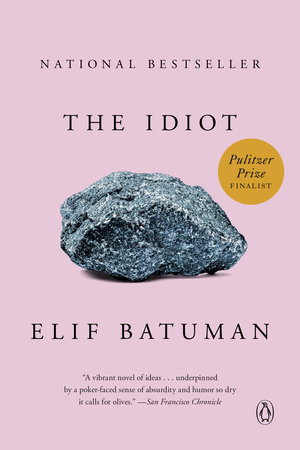

I have not read it cover to cover. I skim the review of Batuman's Either/Or and check my hold at the library; it will easily be September before I read it, my daughter will have started university. (While on the library site, I realize I am #1 on 0 copies of a book that is not available and wonder how I was allowed to reserve it.)

I glance at the piece on Gainza'a Portrait of an Unknown Lady and hope that when I read it later it will enlighten me. What is it about Gainza's books, which I don't particularly enjoy, that inspire me to stubbornly poke and prod at things I don't understand, which — the poking and prodding — I also don't particularly enjoy?

And here, there is a review of Jacqueline Harpman's I Who Have Never Known Men, which title stops me in my tracks.

This mesmerizing oddity opens with a prefatory couple of pages about something—some sort of memoir or testimony—that the narrator has just finished writing:

I was gradually forgetting my story. At first, I shrugged, telling myself that it would be no great loss, since nothing had happened to me, but soon I was shocked by that thought. After all, if I was a human being, my story was as important as that of King Lear or of Prince Hamlet that William Shakespeare had taken the trouble to relate in detail.

I spend days thinking about the title, and thinking about what my story is, it's not one story, it's a multitude. I spend those same days reminding people around me, and myself, that while we may be the hero of our own life, we are not the centre of other people's universes.

It's many more days before I read the review of Harpman's I Who Have Never Known Men and determine that I should read this novel, even while the review is less about the book than it is about the violent and mysterious age we find ourselves in, as Deborah Eisenberg puts it, "our current, very alarming moment." I find myself nodding.

I am the kind of person who picks up a copy, thumbs through it, sets it aside, packs it in her bag to have something to read while waiting, opens it and refolds it, flips back to find that one sentence that caught her eye, thinks about making time to read it later.

*****

There is blood, as usual. I wonder how normal the bleeding is. I don't talk to people about it because I am ashamed. It is a moral shortcoming that I don't floss as often as I should.

Can he sense the tension in my jaw, or see the effects of my teeth clenching? He tells me I should take a vacation, I deserve it.