The narrator of Jonathan Dee's Sugar Street has as little social contact as possible, in the interest of self-preservation, but he is far from silent. There's a jarring meta moment about two-thirds of the way through, when the narrator admits to having always wanted to write a novel, and you think, there is no crime, he is not on the run, he is only disconnecting from the distractions of a banal existence so he can write, these are not his thoughts, they are his character's.How did silence get such a bad rap? Everybody these days things the world of their own voice, things that by raising that voice, they're doing something. Wrong. Nobody except you cares what you have to say. Silence does not equal complicity; silence equals humility and also practicality. Silence turns your attention away from yourself. Am I talking about the importance of listening? Yeah, sure, a little I suppose, but it's more inward looking, more personal than that. Just stop talking, stop posting, stop tweeting. Shut up. A lot opens up to you, to your mind and your senses, once you do that.

Maybe he should just shut up.

He's talking about radio when he says, "Something ugly is eventually released when you keep talking and talking with no idea who's listening to you." But I think the same principle applies to his output.

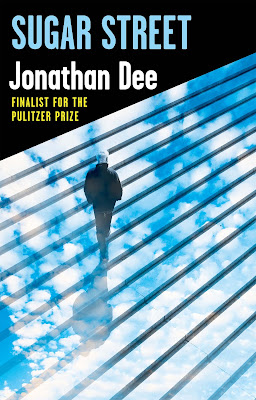

This novel came to my attention because it was long-listed for the 2023 Tournament of Books. For an overview of the setup, see Lionel Shriver's excellent write-up; the book starts much the way Hitchcock's Psycho does, which braces me for the potential stakes. The description, the mood, put me in mind of any number of Simenon stories, where a man walks out on his life. It felt almost fresh in its matter-of-factness, about crime, the state of the world, the inherent shittiness of people.

What a cesspool this world is. Democracy, capitalism, liberalism: all in the lurid end-stages of their own failure, yet we won't even try to imagine anything different, any other principle around which life might be organized: we would sooner choke each other to death, which is basically what we're doing.

I love my fiction with a dose of cynicism, but this book wore me down. Maybe because, still, I Need to Work, and rumours abound about mass layoffs. Maybe because it's cold and I'm tired. Maybe because he's right.

I'm not one of those people who Needs to Work. The whole culture of employment: what does it serve, really? It serves the cause of maintaining the world as it is. You're like a particle of blood circulating through the way things are, and the way things are is pretty fucking toxic, terrible, destructive, nasty, vicious, brutal, and corrosive. In exchange for some money? No. Not anymore. Pass.

So what is he doing here in the middle of nowhere, living a nothing life, without money, without people? What could have life been before for him to walk away from it?

He watches a public protest and wonders what these people were really doing.

"Well, at least we did something," everyone would feel afterward, when in practical terms they had done nothing, except to show themselves something about themselves that they wanted to see [...] so that they might later tell themselves a story about how they'd done everything they could.

Maybe that's what he's doing on Sugar Street, telling himself the same kind of story, that he did something, and that'll appease his his privileged white male conscience about the life he led until he left it.

The world is a ruined place, and that is our doing. Some of us much more that others. Still, it's a fantasy that you are somehow going to make this world better by adding something to it, bringing something to it. The only way to improve this world is to substract from it. Only subtract.