I enjoyed Subtly Worded, by Teffi, and more so because of book club, but probably more for its value as a historical oddity than on its literary merits. This collection is career-spanning and chronologically ordered.

The stories featuring historical figures — Tolstoy and Rasputin — were fascinating to me (more essay than story?).

However, some of the stories made me roll my eyes at the obviousness of their twist endings. They were truly less than subtle. Other bookclubbers disagreed on this point. And there is indeed a cleverness in the way Teffi uses words and makes them central to her stories. The title story, for example, is about censorship — words and meaning and double-meaning. I might argue that these stories are about subtlety more than they exercise it.

Some of this material is satirical, other bits are just plain funny. She has a comedic sense of timing — knows when to keep it short and when to go long. She is a master at capturing ordinary speech.

The introduction states that shortly before her death, Teffi wrote, "An anecdote is funny when it's being told, but when someone lives it, it's a tragedy. And my life has been sheer anecdote, that is — a tragedy."

So why did Teffi fall off the literary map? Because she was a woman? And why is she back?

I can't quite put my finger on why I don't connect with most of Teffi's stories. Some are too light, others too ponderous. Some bookclubbers posited that as a woman, she may have felt compelled to write a certain way, to play into her role as socialite and play to expectations. More style than sincerity?

That said, I favoured a few standouts I wouldn't hesitate to recommend to anyone: "The Quiet Backwater," "Ernest with the Languages," and "The Dog (A Story from a Stranger)."

Reviews

Subtly Worded, and Other Stories by Teffi review – a traditional Russian form is given a good hiding

Compared to Chekhov, Colette and Now Sedaris: 'Subtly Worded' Brings Teffi to Non-Russian Readers

Thursday, August 31, 2017

Comedy and tragedy

Labels:

bookclub,

short stories,

Teffi

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Prufrocked

She... and here I rear back and halt myself, ashamed, prufrocked into a sudden pudeur, for, after all, how should I presume? Shall I say, I have known them all, I have seen her like a yellow fog rubbing her back against, rubbing her muzzle upon, shall I say, licking her tongue into the corners of this evening? Do I dare, and do I dare? And who am I, after all? I am not the prince. An attendant lord, deferential, glad to be of use. Almost, at times, the Fool... But, setting aside poetry, I'm too deeply in to stop now.— from The Golden House, by Salman Rushdie.

|

| Source |

However, I'm only a quarter of the way in, and I'm worried about where Rushdie might be going with this tale with the makings of a presidential parable. We'll see where we end up.

But. Prufrocked! I sat up and paid attention!

I wrote a response to Alfred J. when I was 17.

[I can't find the damn poem. I can't find in anywhere. It's in a puke-beige duotang (not the boring-beige one), along with a weird essay I wrote on Pythagorean dualism. This is a thing I kept for 30 years. Or thought I kept. Did I lose it in the divorce? I mean, physically. Not like that story I lost on a bet. Did I throw it away in anger, or sheer drunken stupidity? Could I have been so careless? Maybe the poem's no good. Maybe I threw it out because it was no good, and I was so horrified by the poem's horribleness, I blocked the whole episode from my memory. Have I merely misplaced it? I grow old.)

Last week I met a boy who writes poetry. He devotes himself to it. He will be a writer. A poet.

It takes guts, being a poet.

Maybe I should've been a poet.

Labels:

poetry,

Salman Rushdie,

T.S. Eliot,

TS Eliot

Saturday, August 26, 2017

The ultimate shiver running up the ultimate spine

Propagating at a significant fraction of the speed of light, a frisson of alarm travelled the length of the Atlantic Space Elevator, like the ultimate shiver running up the ultimate spine.There's a lot going on in The Night Sessions, by Ken MacLeod. It's a police procedural. It's science fiction. It's an ecologically challenged future where religion has been eradicated from public discourse, the Faith Wars having culminated in the discharge of nuclear arms. There's a Third Covenant on the rise in Edinburgh.

And robots are attaining consciousness.

Detecting Hardcastle might or might not be difficult, but preventing that entity from accomplishing whatever it had planned was likely to be violent and, as far as Skulk2 was concerned, terminal. It had been thrown into this unenviable position by its original self, from which its sense of identity was diverging by the millisecond. Skulk2 was still Skulk, with all the original machine's emotions and loyalties, memories and reflections, but it found itself both baffled and despondent about the decision its past self had taken — that blithe disregard for a separate being that was, after all, as close to itself as it was possible to be. Some of that resentment begin to jaundice its feelings about Adam Ferguson. The man had been as casual as Skulk had been in sending his old friend on this probably suicidal mission.I read this book earlier this summer while in Edinburgh. That made for spectacular reading: wandering the wynds of the Old Town by day, and settling into our hotel to read about those same paths by night. Plus I learned a little about the Covenanters along the way, which definitely added to my understanding of the issues in the novel.

Remembering their conversation just before the copying, Skulk2 made a cold assessment of how much separate existence it could experience before it drifted so far from its original that would find the switch to self-sacrifice mode painful. This projection of a future potential state of mind was an absorbing exercise, and in itself intensified its self-awareness. The time, it discovered could be reckoned in minutes.

About two-thirds of the way through my interest waned a bit, partly because of the distractions of vacation, but also the story gets a little chaotic — there are just so many weighty issues in this 260-page novel that they start to suffocate a little. That said, I'd like to come back to this book someday.

Reviews

Los Angeles Review of Books: Taking the Future on Faith

It's here that the capabilities of the robots and their superiority to mere humans becomes clear. It isn't just their speed and versatility, or their ability to toggle their minds from one state to another, from self-preservation to self-sacrifice. Two different characters ask two different robots whether they are saved — whether they have backed up their memories and mental states. On one level, it's a trite pun; on another, it's the kind of science-fictional sentence that creates a new reality by collapsing the gap between metaphor and literal act. Robots can save themselves, and can be resurrected by downloading a copy into a new body. They are, essentially, physically immortal. And it's here, too, that we begin to realize that the conspiracy Ferguson has been so doggedly unraveling cloaks the true meaning of the Third Covenant, that the real story has been happening elsewhere, and that MacLeod has ruthlessly followed the logic of his intelligent, ambitious novel to a conclusion that’s truly world-changing.io9: Do Protestant Terrorist Robots Have Souls?

There is something brilliant in MacLeod's idea that when robots achieve human-style intelligence that they'll become as irrational as humans too.Strange Horizons: The Night Sessions by Ken MacLeod

See also the Complete Review for its comprehensive review round-up.

Labels:

Ken MacLeod,

mystery,

philosophy,

religion,

science fiction

Monday, August 21, 2017

Art is not a mirror but a hammer

I googled "written on the body" and down that rabbit hole I discovered Shirin Neshat.

Shirin Neshat is an Iranian-born visual artist.

See NPR: Artist Shirin Neshat Captures Iran's Sharp Contrasts In Black And White.

(Art is not a mirror but a hammer.)

Shirin Neshat is an Iranian-born visual artist.

See NPR: Artist Shirin Neshat Captures Iran's Sharp Contrasts In Black And White.

(Art is not a mirror but a hammer.)

Labels:

art,

Shirin Neshat

Sunday, August 20, 2017

Apocalyptic body song

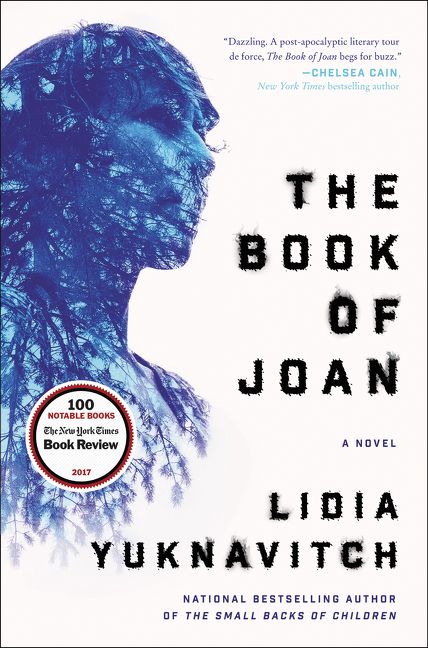

"There is no self and other," she said, laughing into the mouth of death, the blue light at her temple gleaming laser-like into the sky and surrounding air, the song in her head crescendoing in tidal waves and reverberating in the bones of every man, woman, and child around her, her armies plunging and rising as if carried by apocalyptic body song.It's been a while since I read The Book of Joan, but I think I still have things to say about it.

And when she rested her body down upon the dirt, arms spread, legs spread, face down, there was a breach to history as well as evolution.

And the sky lit with fire, half from the weapons of his attack, half from her summoning of the earth and all its calderas — war and decreation all at once, a seeming impossibility.

It was not an easy read for me. Overly literary, almost poetic. That's not always a bad thing. Usually I would blame myself for not connecting with a book. For some reason, this time, I am perfectly comfortable in not taking the blame. Another time, another place, I imagine I would feel similarly, just that I might explain it away differently.

I mean, "apocalyptic body song." Come on.

While the turns of phrase are sometimes beautiful, they took me out of the story rather than propel me along by fleshing it out.

That said, there's an awful lot to think about here. The trajectory on which our planet is headed, ecologically, politically, maybe morally. "We are what happens when the seemingly unthinkable celebrity rises to power." Resources. "Reproduction wasn't what we mourned. We mourned the carnal." The nature of love, gender, energy, power, narrative. "I wonder sometimes if that's why grafting was born. It restores us to the evidence of a body." Physicality and magicality. "The physical world seemed only a membrane between humans and the speed and hum of information." Rebellion.

In 2049 there is a space station colony where live — if you can call it that — Earth's last survivors, among whom 49-year-old Christine, soon to be "aged out" and thus having nothing to lose, grafts the story of Joan onto her body. "What is the word for her body?"

[It's hard not to think that I would be aged out soon, too.]

[It's hard not to think of Jeanette Winterson's Written on the Body. It's been eons since I read it, I don't remember it, but I'm going to go out on a limb and say these novels share some themes and theory.]

Two things have always ruptured up and through hegemony: art and bodies. That is how art has preserved its toehold in our universe. Where there was poverty, there was also a painting someone stared at until it filled them with grateful treas. Where there was genocide, there was a song that refused to quiet. Where a planet was forsaken, there was someone telling a story with their last breath, and someone else carrying it like DNA, or star junk. Hidden matter.Reviews

|

| Shirin Neshat. Divine Rebellion, 2012. |

Now is a fine time for tales of women's resistance, which, above all else, is what The Book of Joan has on offer. Lidia Yuknavitch mines literary and political history for impressive, timely heroines based on the iconic Joan of Arc and her contemporary Christine de Pizan, the only chronicler to write during Joan’s lifetime. Yuknavitch grafts these findings onto layers of material drawn equally from contemporary critical theory, our dire political and ecological realities, and an array of speculative fiction ranging from Shakespeare's The Tempest to Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? In the convoluted folds and counterfolds of her narrative, Yuknavitch binds these various strains together with the fates of an Earth that has not quite survived eco-catastrophe and a parasitic sky realm, CIEL, ruled over by Jean de Men, a sadistic and egotistical television-billionaire-become-dictator: "His is a journey from opportunistic showman, to worshipped celebrity, to billionaire, to fascistic power monger," a rise made possible by the "acquiescence" of the powerful and wealthy.The Rumpus: "A Full-Throated Cry from a Clarion"

In The Book of Joan, the last members of the human race, having "ascended" to a colony in space after a violent event, have lost their sexual organs in a devolutionary process. Insects and reptiles populate the station where these semi-humans orbit a dead Earth; the bugs and lizards are neither animal nor synthetic, but something between. The relationship of Joan, around whom the book revolves, to her companion Leone, is not sexual or platonic but something else. Everything in the novel is both-and, not either-or.Tor.com: "Bodies in Space"

When you center a story in the body, particularly the female body, you're going to have to grapple with ideas of autonomy, consent, life and death. We like the female body when it is wet, unless that wet is urine or period blood. We like the female body when it is DTF, not as much when it is Down To Eat or Down To Fight or, Ishtar save us, Down To Think. As the book twists and turns and changes shape it becomes far less the familiar story of a young girl leading a war, or becoming a nation's sacrificial lamb, and becomes much more about women having control over what is done to their bodies. It also mediates long and hard on those people who want to assert their desire on other people, animals, or the Earth itself.

**********

I can't imagine whom I would recommend this book to. The beauty is all gone now — but the vastness remains, and I can almost feel beauty just under the surface of things. It hurts to look at it.

Sunday, August 13, 2017

What did they do?

"Who's that you're talking to? Who is it you're calling to the table?"— from "The Quiet Backwater," in Subtly Worded, by Teffi.

"Why you, Granny. And you, Grandpa."

"Then that's what you should say. There was a woman who called everyone to dinner with the words: 'Come and sit yourselves down.' But she didn't say, 'Let the baptized souls come and sit themselves down.' So anyone who felt like it came to dinner: they crawled out from on top of the stove, from behind the stove, from the sleeping shelf, from the bench and from under the bench, all the unseen and unheard, all the unknown and undreamt of. Great big eyes peering, great big teeth clacking. 'You called us,' they said. 'Now feed us.' But what could she do? She could hardly feed such a crowd."

"What happened? What did they all do?" asked the girl, goggle-eyed.

"What do you think?"

"What?"

"Well, they did what they do."

"What did they do?"

"They all did what they had to do."

"But what was it they had to do, Granny?"

"Ask too many questions — there's no knowing who'll answer."

I'm reading this because I'm interested — I've been hearing about Teffi — but also for the Reading Across Borders Book Club, which will be discussing the book Wednesday, August 23, at 7, at Librairie Drawn & Quarterly.

See also Ten Things You Didn't Know about Teffi.

Labels:

bookclub,

short stories,

Teffi

Thursday, August 10, 2017

Downstairs neighbour

|

| When a door closes, a window opens. |

He smiles hello as I cross the courtyard to get to the stairs. I live on the second level.

He's married, two kids, but almost always outside on his own with a drink, smoking or vaping. Maybe even waiting for me, I begin to fantasize. Always acknowledges me, with a nod or sometimes even, Bon soir. An affair certainly would be convenient.

My key turns the lock, but the door sticks. It's been getting worse the last few days, must be the humidity. Oh, but it's really sticking this time. I bang on the door to get my daughter's attention, maybe if she pulls from the inside...

Mon voisin, meanwhile, is sitting downstairs, enjoying the evening air and his glass of wine. He can't not hear me; we'd see each other if we were looking.

The door is definitely not opening. I instruct my daughter to open the window, I punch the screen out from its frame. I pass my bag of groceries through first. Thank goodness for the bench outside, it'll give me a leg up.

My daughter is embarrassed for me. It's all so ridiculous.

Once inside, I still can't open the door.

I wonder if the neighbour looked up my skirt.

True story.

Monday, August 07, 2017

Misfit

I'm still trying to wrap my head around Lidia Yuknavitch's The Book of Joan. I thought I didn't like it much — I want to say it's overwritten and self-indulgent. But I'm still thinking about this book, and I still haven't decided how I feel about it. So that's something.

I'll write more about it soon, but in the meantime, here's a TED Talk Yuknavitch delivered last year.

I'll write more about it soon, but in the meantime, here's a TED Talk Yuknavitch delivered last year.

Even at the moment of your failure, right then, you are beautiful. You don't know it yet, but you have the ability to reinvent yourself endlessly. That's your beauty.

Labels:

Lidia Yuknavitch,

writing

Thursday, August 03, 2017

What do we mean by love anymore?

I've been thinking a lot about love lately.

Here's an explication of the idea of love:

Electric Love • Time Lapse from Android Jones on Vimeo.

I've been thinking about love, because I'm wondering if I'm missing some. I might agree that it's a selfish impulse.

I have a few chapters to go to finish The Book of Joan — the days of this summer are long and full. On some level, the book seems to be saying that we have evolved past the narrative of love (or, we will have by the time of the novel's not-too-distant future setting). Love is not to have, it's to be. Yet it laments the private and personal.

How will this love story end?

Here's an explication of the idea of love:

What do we mean by love anymore? Love is not the story we were told. Though we wanted so badly for it to hold, the fairy tales and myths, the seamless trajectories, the sewn shapes of desire thwarted by obstacles we could heroically battle, the broken heart, the love lost the love lorn the love torn the love won, the world coming back alive in a hard-earned nearly impossible kiss. Love of God love of country love for another. Erotic love familial love the love of a mother for her children platonic love brotherly love. Lesbian love and homosexual love and all the arms and legs of other love. Transgressive love too — the dips and curves of our drives given secret sanctuary alongside happy bright young couplings and sanctioned marriages producing healthy offspring.— from The Book of Joan, by Lidia Yuknavitch.

Oh love.

Why couldn't you be real?

It isn't that love dies. It's that we storied it poorly. We tried too hard to contain it and make it something to have and to hold.

Love was never meant to be less than electrical impulse and the energy of matter, but that was no small thing. The Earth's heartbeat or pulse or telluric current, no small thing. The stuff of life itself. Life in the universe, cosmic or as small as an atom. But we wanted it to be ours. Between us. For us. We made it small and private so that we'd be above all other living things. We made it a word, and then a story, and then a reason to care more about ourselves than anything else on the planet. Our reasons to love more important than any others.

The stars were never there for us — we are not the reason for the night sky.

The stars are us.

We made love stories up so we could believe the night sky was not so vast, so unbearably vast, that we barely matter.

Electric Love • Time Lapse from Android Jones on Vimeo.

I've been thinking about love, because I'm wondering if I'm missing some. I might agree that it's a selfish impulse.

I have a few chapters to go to finish The Book of Joan — the days of this summer are long and full. On some level, the book seems to be saying that we have evolved past the narrative of love (or, we will have by the time of the novel's not-too-distant future setting). Love is not to have, it's to be. Yet it laments the private and personal.

How will this love story end?

Labels:

Lidia Yuknavitch,

love,

science fiction

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)