"Scientists have even begun studying the chants," said Frère Sébastien, "trying to explain the popularity of the recording these monks made. People went nuts for it."— from The Beautiful Mystery, by Louise Penny.

"And have they any explanation?"

"Well, when they hooked up probes to volunteers and played Gregorian chants it was quite startling."

"How so?"

"It showed that after a while their brain waves changed. They started producing alpha waves. Do you know what those are?"

"They're the most calm state," said the Chief. "When people are still alert, but at peace."

"Exactly. Their blood pressure dropped, their breathing became deeper. And yet, they also became, as you said, more alert. It was as though they became 'more so,' you know?"

"Themselves, but their best selves."

"That's it. Doesn't work on everyone, of course. But I think it works on you."

Gamache considered that and nodded. "It does. Perhaps not as profoundly as the Gilbertines, but I've felt it."

"While the scientists say it's alpha waves, the Church calls it 'the beautiful mystery.'"

"The mystery being?"

"Why these chants, more than any other church music, are so powerful. Since I'm a monk I think I'll go with the theory they're the voice of God. Though there's a third possibility," the Dominican admitted. "I was at dinner a few weeks ago with a colleague and he has a theory that all tenors are idiots. Something to do with their brain pans and vibration of the sound waves."

Gamache laughed. "Does he know you're a tenor?"

"He's my boss, and he sure suspects I'm an idiot. And he might be right. But what a glorious way to go. Singing myself into stupidity. Maybe Gregorian chants have the same effect. Make us all into happy morons. Scrambling our brains as we sing the chants. Forgetting our cares and worries. Letting the world slip away." The younger man closed his eyes and seemed to go somewhere else. And the, just as quickly, he came back. Opening his eyes he looked at Gamache, and smiled. "Bliss."

"Ecstasy," said Gamache.

"Exactly."

"But for monks it's not just music," said Gamache. "There's also prayer. The chants and prayers. It's a potent combination. Both mind altering, in their way."

When the monk didn't say anything, Gamache continued.

"I've sat here for a number of services now and watched the monks. To a man they go into a sort of reverie when singing the chants. Or even just listening to them. You did it just now, just thinking about the chants."

"Meaning?"

"I've seen that before, you know. On the faces of drug addicts."

It's one of few memories I have of my father. I was 4, and he took me to church. My mother must have been not feeling well, it was just him and me. I'm sure I fidgeted; I was a good kid, but even then I remember not believing in God. A stern look from my father was enough to still me. But what I remember is him, afterward, amused, telling my mother that I hum along with the priest's chanting. The chanting – that was the only reason I tolerated mass.

I've been self-conscious about my humming ever since. It's stronger than me, the instinctive urge to hum along with almost any type of music. Humming, chanting, is weirdly both physical and spiritual, whether I'm practicing yoga or blissed out on sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll.

Home sick in bed for a couple days last week, I glutted on Louise Penny, downloading whatever my library had readily available. In brief:

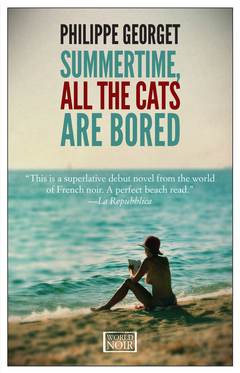

The Beautiful Mystery is set in a monastery in Northern Quebec, completely removed from the village of Three Pines and its inhabitants. Featuring a small, reclusive order of monks once thought vanished, the rule of silence is lifted so that the brothers can help the investigation into the murder of the choirmaster, who was responsible for the recording of chants that brought the order out of obscurity. Although they indulge in chocolate-covered blueberries, Chief Inspector Gamache and Inspector Beauvoir wrestle with powerful personal demons in this one. Monks, music, and manuscripts — this book was heaven for me.

The Long Way Home, on the other hand, is dependent on some familiarity with the cast of regulars in Three Pines. Gamache's wife plays a larger role than I remember in other books, but this is only natural as she is now a resident of the community, the couple having decided to retire there. While the cast travels first to Toronto and then across Quebec to the stony mouth of the Saint Lawrence, the story journeys into the heart of Quebecois art, with a layover at the Garden of Cosmic Speculation.

The Hangman is disappointing. You need to know that this story was written as part of a series designed to encourage adult literacy. It's simplistic, not nuanced at all. It has the kernel of a good story, but the plotting and characterization are thin. Chronologically the events of this book fall between numbers 6 and 7 in the Inspector Gamache series, but it hardly matters, as there are no developments in the greater character or story arcs. It's short, easy to read, and still compelling, and therefore suitable for its target audience, but you won't miss anything if you skip this one.

If I had a cottage, I'd be sure to stock its shelves with a complete set of Penny's books.