The execution

Inky and tentacled

He also maintains he doesn't mind if people still identify him primarily as the author of Flaubert's Parrot. He mentions a story of someone asking the late Kingsley Amis if Lucky Jim, Amis's most famous novel, was an "albatross" around his neck. It's better than having no albatross, Amis replied. "I thought that was a very good reply," Barnes says. "So I have a parrot around my neck."

Don Quixote went up to Sancho, and in his ear he whispered:

"Sancho, just as you want people to believe what you have seen the sky, I want you to believe what I saw in the Cave of Montesinos. And that is all I have to say."

One finds the obsession with cleanliness everywhere in Bleak House. Dickens's filthmeter is always turned on. It goes into whirring overdrive in such scenes as that of the first visit to the brickmakers' hovel in St Alban's. "Is my daughter awashin?" asks the drunken brute of a brickmaker, in response to Mrs Pardiggle's condescending inquiries as to the state of his soul and whether he has read the uplifting tracts she has kindly left him: "Yes, she is awashin. Look at the water. Smell it! That's wot we drinks. How do you like it, and what do you think of gin, instead? An't my place dirty? Yes, it is dirty - it's nat'rally dirty, and it's nat'rally unwholesome; and we've had five dirty and onwholesom children, as is all dead infants, and so much the better for them, and for us besides. Have I read the little book wot you left? No, I an't read the little book wot you left."

"La forza del destino" is an Italian phrase meaning "the force of destiny," and "destiny" is a word that tends to cause arguments among the people who use it. Some people think destiny is something you cannot escape, such as death, or a cheesecake that has curdled, both of which always turn up sooner or later. Other people think destiny is a time in one's life, such as the moment one becomes an adult, or the instant it becomes necessary to construct a hiding place out of sofa cushions. And still other people think that destiny is an invisible force, like gravity, or a fear of paper cuts, that guides everyone throughout their lives, whether they are embarking on a mysterious errand, doing a treacherous deed, or deciding that a book they have begun reading is too dreadful to finish. In the opera La Forza del Destino, various characters argue, fall in love, get married in secret, run away to monasteries, go to war, announce that they will get revenge, engage in duels, and drop a gun on the floor, where it goes off accidentally and kills someone in an incident eerily similar to one that happens in chapter nine of this very book, and all the while they are trying to figure out if any of these troubles are the result of destiny. They wonder and wonder at all the perils in their lives, and when the final curtain is brought down even the audience cannot be sure what all these unfortunate events may mean.

The canon agreed, and going on ahead with his servants, listened with attention to the account of the character, life, madness, and ways of Don Quixote, given him by the curate, who described to him briefly the beginning and origin of his craze, and told him the whole story of his adventures up to his being confined in the cage, together with the plan they had of taking him home to try if by any means they could discover a cure for his madness. The canon and his servants were surprised anew when they heard Don Quixote's strange story, and when it was finished he said,

"To tell the truth, senor curate, I for my part consider what they call books of chivalry to be mischievous to the State; and though, led by idle and false taste, I have read the beginnings of almost all that have been printed, I never could manage to read any one of them from beginning to end; for it seems to me they are all more or less the same thing; and one has nothing more in it than another; this no more than that. And in my opinion this sort of writing and composition is of the same species as the fables they call the Milesian, nonsensical tales that aim solely at giving amusement and not instruction, exactly the opposite of the apologue fables which amuse and instruct at the same time. And though it may be the chief object of such books to amuse, I do not know how they can succeed, when they are so full of such monstrous nonsense. For the enjoyment the mind feels must come from the beauty and harmony which it perceives or contemplates in the things that the eye or the imagination brings before it; and nothing that has any ugliness or disproportion about it can give any pleasure. What beauty, then, or what proportion of the parts to the whole, or of the whole to the parts, can there be in a book or fable where a lad of sixteen cuts down a giant as tall as a tower and makes two halves of him as if he was an almond cake? And when they want to give us a picture of a battle, after having told us that there are a million of combatants on the side of the enemy, let the hero of the book be opposed to them, and we have perforce to believe, whether we like it or not, that the said knight wins the victory by the single might of his strong arm. And then, what shall we say of the facility with which a born queen or empress will give herself over into the arms of some unknown wandering knight? What mind, that is not wholly barbarous and uncultured, can find pleasure in reading of how a great tower full of knights sails away across the sea like a ship with a fair wind, and will be to-night in Lombardy and to-morrow morning in the land of Prester John of the Indies, or some other that Ptolemy never described nor Marco Polo saw? And if, in answer to this, I am told that the authors of books of the kind write them as fiction, and therefore are not bound to regard niceties of truth, I would reply that fiction is all the better the more it looks like truth, and gives the more pleasure the more probability and possibility there is about it. Plots in fiction should be wedded to the understanding of the reader, and be constructed in such a way that, reconciling impossibilities, smoothing over difficulties, keeping the mind on the alert, they may surprise, interest, divert, and entertain, so that wonder and delight joined may keep pace one with the other; all which he will fail to effect who shuns verisimilitude and truth to nature, wherein lies the perfection of writing. I have never yet seen any book of chivalry that puts together a connected plot complete in all its numbers, so that the middle agrees with the beginning, and the end with the beginning and middle; on the contrary, they construct them with such a multitude of members that it seems as though they meant to produce a chimera or monster rather than a well-proportioned figure. And besides all this they are harsh in their style, incredible in their achievements, licentious in their amours, uncouth in their courtly speeches, prolix in their battles, silly in their arguments, absurd in their travels, and, in short, wanting in everything like intelligent art; for which reason they deserve to be banished from the Christian commonwealth as a worthless breed."

The curate listened to him attentively and felt that he was a man of sound understanding, and that there was good reason in what he said; so he told him that, being of the same opinion himself, and bearing a grudge to books of chivalry, he had burned all Don Quixote's, which were many; and gave him an account of the scrutiny he had made of them, and of those he had condemned to the flames and those he had spared, with which the canon was not a little amused, adding that though he had said so much in condemnation of these books, still he found one good thing in them, and that was the opportunity they afforded to a gifted intellect for displaying itself; for they presented a wide and spacious field over which the pen might range freely, describing shipwrecks, tempests, combats, battles, portraying a valiant captain with all the qualifications requisite to make one, showing him sagacious in foreseeing the wiles of the enemy, eloquent in speech to encourage or restrain his soldiers, ripe in counsel, rapid in resolve, as bold in biding his time as in pressing the attack; now picturing some sad tragic incident, now some joyful and unexpected event; here a beauteous lady, virtuous, wise, and modest; there a Christian knight, brave and gentle; here a lawless, barbarous braggart; there a courteous prince, gallant and gracious; setting forth the devotion and loyalty of vassals, the greatness and generosity of nobles. "Or again," said he, "the author may show himself to be an astronomer, or a skilled cosmographer, or musician, or one versed in affairs of state, and sometimes he will have a chance of coming forward as a magician if he likes. He can set forth the craftiness of Ulysses, the piety of AEneas, the valour of Achilles, the misfortunes of Hector, the treachery of Sinon, the friendship of Euryalus, the generosity of Alexander, the boldness of Caesar, the clemency and truth of Trajan, the fidelity of Zopyrus, the wisdom of Cato, and in short all the faculties that serve to make an illustrious man perfect, now uniting them in one individual, again distributing them among many; and if this be done with charm of style and ingenious invention, aiming at the truth as much as possible, he will assuredly weave a web of bright and varied threads that, when finished, will display such perfection and beauty that it will attain the worthiest object any writing can seek, which, as I said before, is to give instruction and pleasure combined; for the unrestricted range of these books enables the author to show his powers, epic, lyric, tragic, or comic, and all the moods the sweet and winning arts of poesy and oratory are capable of; for the epic may be written in prose just as well as in verse."

This past weekend was its final run of the season. Both the summer and our carousel ride were commmemorated in a small way this week by Helena digging out her souvenir T-shirt. It's too big for normal wear, but I struck a deal with her — if she dressed in sensible clothes for daycare, she could wear the carousel shirt to sleep in.

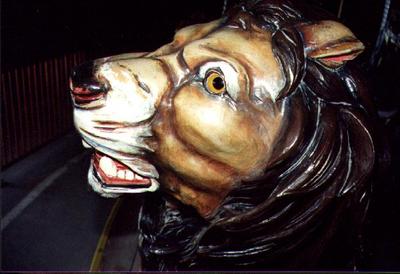

This past weekend was its final run of the season. Both the summer and our carousel ride were commmemorated in a small way this week by Helena digging out her souvenir T-shirt. It's too big for normal wear, but I struck a deal with her — if she dressed in sensible clothes for daycare, she could wear the carousel shirt to sleep in.According to the U.S. National Carousel Association, between 3,000 and 4,000 wooden carousels were carved across North America between the years 1885 and 1930. Today, less than 150 of these original carousels are left, and only 9 historic carousels reside in Canada.

Midway hawkers calling

'Try your luck with me'

Merry-go-round wheezing

The same old melody

A thousand ten cent wonders

Who could ask for more

A pocketful of silver

The key to heaven's door

Niagara Woodcarvers are helping the Friends of the Carousel (a not-for-profit organization) with the ongoing restoration project. There's also a gift shop now, with all proceeds helping to fund the work. In addition to the T-shirt, we bought a sticker book for Helena.

Niagara Woodcarvers are helping the Friends of the Carousel (a not-for-profit organization) with the ongoing restoration project. There's also a gift shop now, with all proceeds helping to fund the work. In addition to the T-shirt, we bought a sticker book for Helena.Sources show it currently has a Frati band organ which plays Wurlitzer 150 rolls, and that this organ was refurbished in 1985. The Artizan organ resides in The St. Catharines Historical Museum, having been moved there in 1976.

Another important setting in my childhood and early teens was Lakeside Park, in Port Dalhousie...When I was fourteen and fifteen, I worked summers at Lakeside Park as a barker ('Catch a bubble, prize every time,' all day and night)... And there was music: some of the kids brought transistor radios to work, and the music of that summer of 1966 played up and down the midway... At night, when the midway closed, we gathered around a fire on the beach, singing... Lakeside Park resonated in my life in so many deep ways, especially those fundamental exposures to music that would be forever important... It's all gone now. All that's left, apart from memories, is the old merry-go-round...

Some journalists have behaved appallingly. They've been ringing on the door insisting on entrance. They don't like it if you don't respond like a chimpanzee. But I'm not a chimpanzee and I don't intend ever to be a fucking chimpanzee. Not that I've anything against chimpanzees.

In 1958 I wrote the following:

"There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false."

I believe that these assertions still make sense and do still apply to the exploration of reality through art. So as a writer I stand by them but as a citizen I cannot. As a citizen I must ask: What is true? What is false?

Considered Britain's greatest living playwright for plays like The Birthday Party, The Caretaker and The Homecoming, "Pinter restored theatre to its basic elements: an enclosed space and unpredictable dialogue, where people are at the mercy of each other and pretence crumbles," the academy said.

Though a human rights activist since the early 1970s, Pinter has recently become more outspoken about politics, specifically criticizing U.S. President George W. Bush, British Prime Minister Tony Blair and the war in Iraq.

Dirty dishes are a blessing, because when they are put away I am blessing my family. Laundry is the same way. I am no longer chained to a chore but I have been given a chance to show my sweet darling that I care for him. After all, nothing says I love you, like clean underwear. So when we have a change in our attitude from feeling martyred to finding joy in blessing our family, we will have time to do just a little.

addressing Aramis, [the governor] added in a lower tone of voice, 'Do you know what it is? I warrant it is something about as interesting as this: "Keep fire away from you powder magazine," or, "Keep an eye on so-and-so; he is an expert gaol-breaker."'

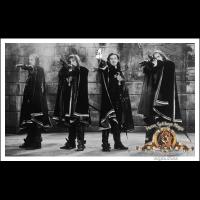

Did you see the movie? With those gloriously cast aging musketeers? The book is nothing like that. The movie picks up a plot point that in my edition begins on page 178 (of 616) and carries on for maybe two hundred pages, but it's difficult to measure precisely because the movie goes off to resolve that plot in a wildly different (if still thrillingly entertaining) manner. (That bit where the 4 of them charge the line of musketeers at the Bastille and they're shocked when the smoke clears to find themselves still standing — I love that scene. But this scene is not to be found in the book; I don't think the 4 of them are ever even together on the same page in the book.)

Did you see the movie? With those gloriously cast aging musketeers? The book is nothing like that. The movie picks up a plot point that in my edition begins on page 178 (of 616) and carries on for maybe two hundred pages, but it's difficult to measure precisely because the movie goes off to resolve that plot in a wildly different (if still thrillingly entertaining) manner. (That bit where the 4 of them charge the line of musketeers at the Bastille and they're shocked when the smoke clears to find themselves still standing — I love that scene. But this scene is not to be found in the book; I don't think the 4 of them are ever even together on the same page in the book.)