Noble people don't do things for the money, they simply have money, and that's what allows them to be noble. They don't really have to think about it much; they sprout benevolent acts the way trees sprout leaves.So says Felix's figment daughter Miranda of her father, who's staging The Tempest at a local correctional facility and casting himself as Prospero. Hag-Seed, like The Tempest which it retells, is about vengeance, that most noble of acts.

I'm an Atwood fan from way back — 30 years now. I'm more familiar with Atwood than I am with Shakespeare. Sure, I like Shakespeare as much as anyone does — I acknowledge his genius even if I don't always recognize it. But Atwood never fails to disappoint. Noble Atwood sprouting devourable fiction.

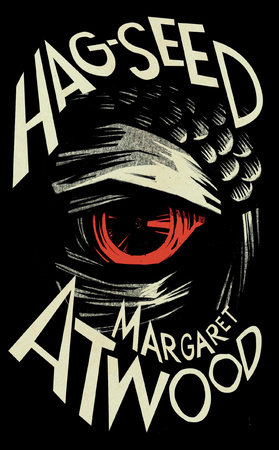

The reviews of Margaret Atwood's Hag-Seed: The Tempest Retold are quite boring in their consistent and unsurprising praise for her wit and overall skill. There is nothing, absolutely nothing, to find fault with. That may not sound much like praise; more like the absence of criticism. It's a relatively compact, near-perfect novel.

So I'm not sure what I can offer you by way of review. I give you this.

You don't need to know anything about The Tempest to enjoy Atwood's Hag-Seed.

I don't know The Tempest. I always assumed it must be cool, based on it being quoted by Laurie Anderson in Blue Lagoon; oh, and by Eliot in The Wasteland. I did see Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books, but, visually and aurally stunning as it was, it can't be said that I understood it. I suspect that knowledge of Shakespeare's original would give the reader an added layer or two of appreciation, but it's not a prerequisite for reading this book.

I now want to see The Tempest staged.

More specifically, I want to see Atwood's version of The Tempest staged, just as she outlines the direction in this novel. A cloak of the pelts of stuffed animals, heads and all, nightmarified Disney princess puppets, rap musical numbers. Sounds awesome. (A couple reviews nitpick that Atwood's rhymes are substandard. I didn't find them out of place.)

Atwood is a master of language.

One character is described as "a diagram of woe." I love that. Her passages may not be liltingly beautiful, but they are crafted to great effect.

There's a click. The door unlocks and he walks into the warmth, and that unique smell. Unfresh paint, faint mildew, unloved food eaten in boredom, and the smell of dejection, the shoulders slumping down, the head bowed, the body caving in upon itself. A meagre smell. Onion farts. Cold naked feet, damp towels, motherless years. The smell of misery, lying over everyone within like an enchantment. But for brief moments he knows he can unbind that spell.Atwood is a skilled storyteller.

While reading Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel, I kept thinking how much it felt like a Margaret Atwood novel, just missing some unpindownable something that would make it great and lasting. So it was interesting to read Atwood so shortly afterwards. Both novels cover the production of Shakespeare. I know it's not fair to compare them — these books set out to do very different things. But I keep trying to figure out, what is it in Station Eleven that reminds me so much of Atwood, and why it falls short of Atwood. Atwood's Hag-Seed is clearly focused and controlled. Maybe this: maybe Station Eleven is trying to be bigger than it needs to be; Hag-Seed is only as big as it needs to be and is careful not to let anything else in.

This book teaches me a new way of reading.

Hag-Seed is a lesson in how to read critically, and this evolves quite naturally out of the context, is never didactic. Felix teaches the prisoners how to read — really read — The Tempest: what do the words mean, what do they really mean, what do they say about the characters who speak them, what is the nature of these characters, human or otherwise, what makes them who they are, why do they do what they do. What happens to them when the play is done? Felix asks his actors to imagine their characters' lives after Shakespeare leaves off. What happens after can inform what happened before. I'm not overly interested in close reading, I read novels for fun, but I think the best works of literature inspire these questions anyway, leading readers to run away with their thoughts. Shakespeare does it. Atwood too.

Atwood on rewriting The Tempest in The Guardian:

The last three words Prospero says are "Set me free." But free from what? In what has he been imprisoned?

1 comment:

So excited to read this! I just got my copy in the mail Friday and am trying to figure out when I might be able to slip it onto the reading pile!

Post a Comment